objects in diaspora

The text traces the development of French ethnological museology, [ 1 ] 1. The author is grateful to Maria Silina for drawing attention to the theme of French ethnological museology. from the influence of 1920s Surrealism and the socialist museum of universal ethnographic humanism of the 1930s to the current debates, focused particularly on the Musée du quai Branly, regarding the re-aestheticisation of objects of “other” cultures and objects in diaspora. The author proposes the concept of “republican museology” as a useful crystallisation of what has occurred in recent decades.

1. Ethnography is generally understood to be the field study of social and cultural groups. And ethnology compares the results obtained by ethnographers in order to arrive at certain generalisations about human nature. The key feature of ethnology understood in this way is the comparative method, which aspires to a certain theoretical meta-level with respect to ethnography, since ethnography is exclusively concerned with observation of the facts of specific cultures.

The French tradition preferred to call itself ethnological. Starting at least from Émile Durkheim in the second half of the 19th century, French researchers focused on decoding cultural reality. In the process, the border between sociology and ethnology was blurred, i.e., the study of cultures was understood primarily as the study of “social facts” (Durkheim’s term). While the Anglo-Saxon tradition continued to describe various ethnographic and cultural formations as values that have an indubitably unitary nature, the French sought to perceive them as semantic sign systems. The French approach revealed the social construction of cultures and opened the way for full cultural relativism, where different cultures are merely different systems of signs and conventions. James Clifford expressed this by saying that the French ethnological tradition is highly sensitive to the over-determination of total social facts.

Paradoxically, the belief in complete semantic cultural relativism gave rise to a search for cultural, or more ontologically profound, invariants — universals that unite people beyond the confines of constructed symbolic cultural systems. So French ethnology produced generalisations about human nature, justifying its more theoretical character compared with ethnography. And if one believes a “Cartesian” tendency, a rational dissection of the world, to be the distinguishing feature of French thought, this dual process of deconstructing cultural and social facts and then searching for humanistic universals (what are left after the semantic “dissection”), is a very clear manifestation of that thought.

In regard to museums, these issues were exercised most clearly in the encounter with objects of other cultures. It could be said all of the challenges described above originate from a certain perplexity in the presence of an other object, an object that denotes a world outlook and life practice that are radically different from those accepted in the society, to which the ethnologist belongs. That encounter spurs research to find answers to certain questions: why is this object other and what exactly is other about it; to what practices does its other form lead; and, finally, is it really so completely other, or does the effect, which it produces on us, in fact depend on something we have in common with it?

French colonialism brought home a generous supply of objects that posed these questions, and private collections and museums became places of encounter with the Other.

2. From 1878, ethnographic objects were amassed in the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris (the Troca as it was familiarly known), a building in outlandish Byzantine-Moorish style. The collection was poorly organised and presented, resembling a repository of strange things rather than a museum. By the turn of the 20th century, what visitors found here was a dust-covered miscellany of unlabelled objects in an unheated and inadequately lit space. The impression, according to contemporary accounts, was mystical.

From the 1910s the Troca suddenly became a place of pilgrimage for innovative artists. It was where, in 1907, Picasso discovered African art. What the Troca and private collections of ethnographic objects offered to Picassos and other future heavyweights of 20th century art were examples of an other aesthetic, which they could set against the European aesthetic.

This felt like the birth of the Contemporaneity, in opposition to the linear, narrative, Western-centred Modernism (the logic of the modern period). Proto-postmodernist, or proto-contemporary views were well represented among the international avant-garde, which was gathered in France at that time, notably among the surrealists and some ethnologists. The ideologues of left-wing Eurasianism, a trend in Russian émigré thought, also had close ties with this environment. [ 2 ] 2. The connections were at the level of both people and ideas. The ideologists of left-wing Eurasianism, Petr Suvchinsky and Dmitry Svyatopolk-Mirsky were primarily critics (music and literary, respectively). Hence their ability to transform Eurasianism, for the purposes of their left-wing project, from its previous status as a humanitarian scientific theory (a concept) into a percept, a conscious all-encompassing utopia, in which a general philosophical theory was supplemented by aesthetics and political activism. Its tasks in the French context — corrosive criticism of the Western cultural order and the provision of alternatives — put left-wing Eurasianism in sync with surrealism and ethnology. Suvchinsky was personally and professionally associated with many avant-garde activists, including Igor Stravinsky and André Shaeffner (an ethnologist and member of staff at the Trocadéro). For more details see: Smirnov, N. "Left-wing Eurasianism and Postcolonial Theory" // e-flux Journal, # 97, February 2019). In 1928, for example, the émigré composer Vladimir Dukelsky (Vernon Duke) published a programme article in the Russian-language Paris newspaper Eurasia entitled “Modernism against the Contemporaneity”, in which he championed the Contemporaneity in opposition to Modernism. The Contemporaneity was understood by Dukelsky and those of like mind as the substitution of a geographical for a historical understanding of the World, and of a spatial, egalitarian understanding for one that was linear and progressive (and thereby repressive). The avant-gardists sought real alternatives to the indulgent orientalism of the 19th century and made cultural relativism possible. By an irony of fate, the authors of the Contemporaneity project — rebels against Modernism — were later dubbed “classics of Modernism”, and their logic was called the “modernist cultural attitude”.

the aim of the eco-museum was to involve people in the process of museum creation, bringing them together around the project, making them actors in and users of their heritage, creating a community database, and thereby initiating a discussion within the community about self-reflective knowledge.

By the mid-1920s, the Troca was a fashionable place and the Contemporaneity project — or, according to accepted terminology, the “modernist cultural attitude” – was in full flood. In 1925−1926, the Institut d’ethnologie was opened in Paris, the manifesto of Surrealism was published, Josephine Baker played her first season at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées and the Eurasian seminar “Russia and Europe” was held next to the Troca. The neighbourhood of these last two is striking, since their missions were similar: they radically questioned the norms of European, Western culture and offered alternatives from other geographical contexts.

The deep relationship between Surrealism and the emerging modernist ethnography has been described in some detail by James Clifford. [ 3 ] 3. Clifford, J. "On Ethnographic Surrealism" // Comparative Studies in Society and History, 1981, October, vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 539-564. Ethnology [ 4 ] 4. Here we use the term "ethnology", which, in terms of its content, is closer to the French tradition. However, in the cited text Clifford ignores the traditions of self-description of French ethnology and makes use exclusively of the term "ethnography" as being more universal. So Clifford's "French ethnography" is the equivalent of our "ethnology". provided a science-based levelling of cultural norms, which entailed a reset of all generally accepted cultural categories (“beautiful”, “ugly”, “sophisticated”, “savage”, “music”, “art”, etc.). Ethnology and the other objects, which it provided, were the wild card or joker in the pack — the card that can take on any value. In the 1920s the young generation of French scholars (Michel Leiris, Marcel Griaule, Georges Bataille, Alfred Métraux, André Schaeffner, Georges Henri Rivière, Robert Desnos) divided their interest between ethnology, poetry and surrealist art. All of them attended the ethnology lectures of Marcel Mauss, who was the link between the sociological ethnology of his uncle and teacher, Émile Durkheim, and the new generation, which shaped modernist ethnology. Mauss’ lectures used a “surrealist” technique: collating and comparing data, conclusions and facts from different contexts. This often led to inconsistencies, which Mauss did not seek to dissolve within the framework of a single narrative or point of view. He is credited with the adage, “Taboos are made in order to be broken”, to which Bataille’s later theory of transgression is a close correlate.

The long friendship between Bataille and the field ethnologist Alfred Métraux symbolises this single field of ethnology and surrealism in the 1920s, and the publication of Documents magazine in 1929−1930, under the editorship of Georges Bataille, can be viewed as the joint achievement of the two movements. The magazine combined texts by ethnographers, semantic analyses of contemporary French culture (including mass culture, such as the Fantômas books), and essays on contemporary artists. For example, the Polish-Austrian art historian Józef Strzygowski in his article “‘Recherches sur l’art plastique’ et ‘Histoire de l’art'” http://redmuseum.church/smirnov-objects-in-diaspora#rec172587079[5] called for linear historical narratives in the study of art to be replaced by plastic formal analysis, for a geographical instead of a chronological view of the World, using maps instead of history as a measure, and filling gaps with monuments (plastic art research instead of art history). In an illustration to the text, he visually compared the plans of three churches: Armenian, German and French. The comparison shows that they are all similar and reproduce an initial structure, which is seen in it most “pure” form in the (oldest) Armenian church. Strzygowski’s conclusion, overturning established cultural hierarchies, was that “Rome is from the East”.

In the second issue of Documents in 1929, Carl Einstein, poet, art theorist and author of the important article “La plastique nègre” (1915), offered an ethnological study of the contemporary artist, André Masson. The study deserves to be called ethnological because it argues that Masson used psychological archaism in his paintings and turned to mythological formations akin to totemic identification for the creation of his artistic forms.

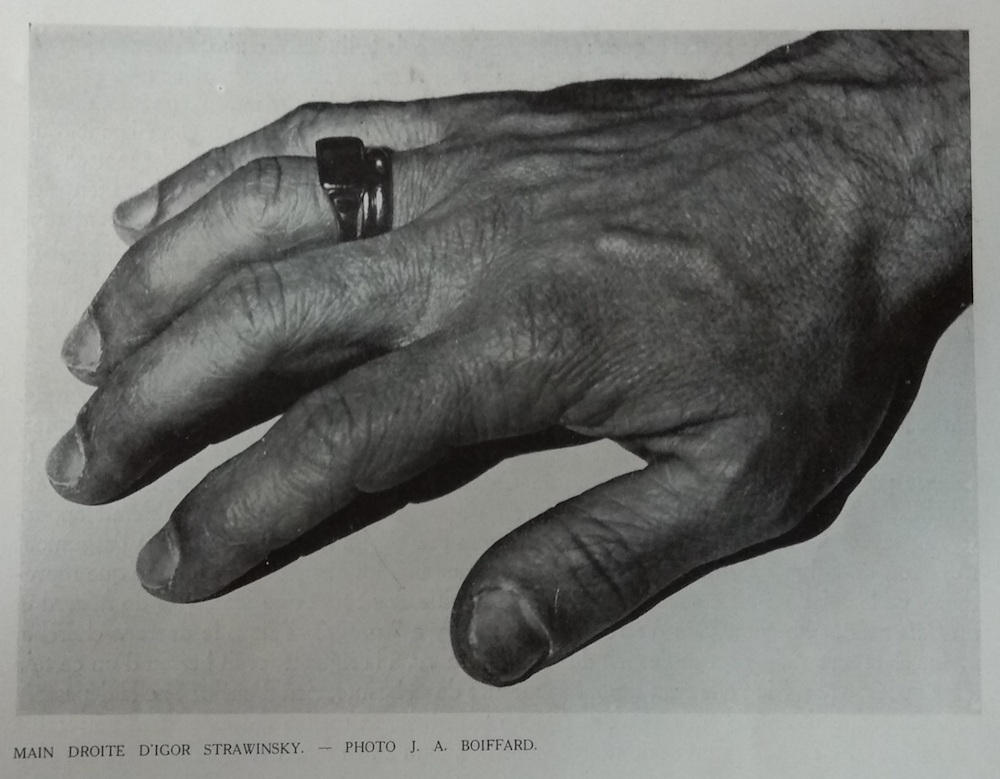

This method of searching for mythological formations and an ontological universal archaic explains the interest of Documents in parts of the body. In two essays on civilisation and the eye, in the fourth issue of 1929, Michel Leiris writes that all civilisation is a thin film on a sea of instincts. When various cultural conventions are laid aside and cultures are deconstructed, what remains is a “dry residue”, outside the bounds of civilisation, such as the eye or the big toe.

It is not surprising that the fictional idol of French popular culture, Fantômas — a fierce criminal and sociopath, a character without identity who dons various masks to commit crimes against his own culture — was among the favourite topics of Documents. His cruelty and sociopathic attitude towards his compatriots matched the “cruel” analysis and dismemberment of their own cultural order, which the surrealists and ethnologists undertook in their transgressive role as cultural “criminals” or “terrorists”.

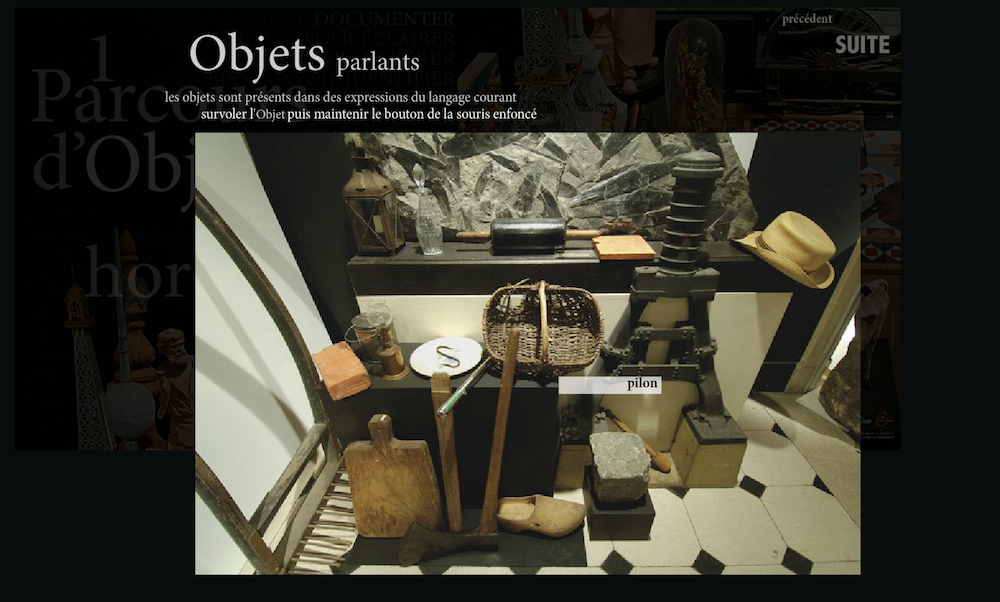

Documents was compiled on a collage principle and was, in essence, a museum that subverted and disrupted cultural standards. It was a playful collection of images, samples, objects, texts and signatures, a semiotic museum, which, in the words of James Clifford, did not strive for cohesion, but reassembled and transcoded culture through collage. Any divisions between “high” and “low” were discarded, everything was deemed worthy of collection and exhibition, so the only task was that of classification and interpretation. The combinations on the pages of Documents are a question analogous to that, which is posed by an ethnographical exhibition. By combining materials and images on the pages of the magazine, its authors carried out the same function as modernist ethnologists working in the museum.

The cultural climate of the 1920s gave the Trocadéro a new lease of life in the later part of the decade. In 1928, Paul Rivet, one of the founders of the Institut d’ethnologie, became director of the Museum. He involved the young museologist, Georges Henri Rivière, in his work at the Trocadéro. The two men, each of them key figures in French ethnological museology, immediately set to work reorganising the collection.

Paris was seized by a craze for everything that was “other”. Wealthy collectors begin to patronise the Troca. Star-studded fashion shows and boxing tournaments were held to raise money for new expeditions such as the Dakar-Djibouti Mission, the main purpose of which was to collect new ethnographical exhibits. However, the single undifferentiated field of ethnology and Surrealism, with their shared orientation towards semantic critique of their own culture, began to disintegrate. The work of corrosive, i.e., “questioning”, deconstructing analysis of reality had been completed, and each of the two spheres began to acquire its own definite outlines. Surrealism soon had its own institutions and specialised print media, in which the new art was associated with the internal, visionary approach of the Breton mainstream faction, from where it is not far to the old, conservative figure of the artist-genius who creates worlds from his inner experience. Ethnology, for its part, affirmed cultural relativism and went in search of universals of human nature.

3. The transformation of the Trocadéro into the Musée de l’homme (“Museum of Man”) has to be understood in the political context of France in the 1920s and 1930s. Paul Rivet, the founder of the Musée de l’homme, was a convinced socialist and his new museum sent a political message. A left-wing left coalition consisting of the French section of the Socialist Workers International (SFIO) and representatives of the Radical Party has been in power in the country since 1924. Despite its “radical” name, the party occupied liberal-progressive positions: its members could only be considered radicals in the context of an exclusively bourgeois and conservative political environment and in the absence of strong socialist and communist parties. The Radical Party was the oldest political party in France, and its position was analogous to that of the Russian Narodniks (“People’s Party”) or of Evgeny Bazarov (fictional hero of Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons) in the conservative, bourgeois environment of the late 19th century. At that time the French Radical Party had been truly radical, but by the 1920s it had shifted to a centrist position, defending market-oriented freedoms.

By the mid-1930s, leftist intellectuals had become acutely aware of the dangers of fascism. In 1934, right-wing street demonstrations led to the break-up of the left coalition government, and anti-fascist intellectuals began to mobilise against the perceived threat. In the same year Rivet was among the founders of the Comité de vigilance des intellectuels antifascistes (“Vigilance Committee of Antifascist Intellectuals”, CVIA), which brought together representatives of the French section of the Workers International, the Radical Party and the Communists in an unlikely alliance. The CVIA can be seen as the prototype of the Popular Front government, which was formed in 1936 from representatives of the same three main leftist parties. The period of office of this government (1936−1938) was the high tide of left-wing ideology in France, and it was during these years that the Musée de l’homme was opened.

Universal humanism, declared as the programme of the Musée de l’homme, was the embodiment of the CVIA’s international humanism, a manifesto of anti-fascist socialist universalism. The Museum asserted the primacy of universal values over cultural differences (prized by the fascists and by right-wing ideologies in general), championing the mind against the aura and magic of the object. The creators of the Museum believed that the divisions of political geography are just as arbitrary as cultural divisions within humanity.

The cosmopolitanism of the Musée de l’homme was the dialectical heir of the collapse of hierarchies in the surrealist ethnography of the 1920s. After the work of total cultural relativisation has been carried out, no single cultural whole, including that of one’s own culture, could be taken as foundational. Under the growing shadow of fascism, the Museum postulated a single humanity, emphasising what was in common rather than what was different.

What was left after the fragmentation of the 1920s? A considerable amount was left: the shared biological evolution of humankind, the archaeological remains of primeval history and the assertion of the equal value and equal rights of today’s cultural alternatives. The museum no longer executed corrosive analysis of the cultural codes of reality. French ethnology abstracted from different and equal symbolic constructions of cultures to obtain the integral humanism of Mauss and Rivet and, later, the human spirit of Claude Lévi-Strauss.

This was, without a doubt, a progressive attitude, and the Musée de l’homme became a symbol of the ideas of the Popular Front in the pan-European socio-political context of those years. The old Byzantine-Moorish Trocadéro building was demolished and replaced by the modernist Palais de Chaillot as part of large-scale reformatting of the architectural landscape in central Paris and preparations for the World Exhibition of 1937. Just as modernist ethnology abstracted from cultural specifics and differences, beloved of Orientalism and emphasised by the political right, the new palace used only the “pure”, abstract forms that remained after the reduction of the historical stylisations and architectural historicisms of the 19th century (the “Moorish” decoration and “Byzantine” roof of the old Trocadéro). Abstraction also meant the search for universal human foundations and the rejection of any cultural hegemony.

The main practical consequence of such an ideology for actual museum exhibitions was much broader contextualization: the exhibits were shown with titles and explanations, placed in the context of their function, and distanced from the viewer in glass cabinets. Objects of “primordial art” were radically de-aestheticised and considered as functional and symbolic components of specific cultures. The Musée de l’homme preserved geographical divisions, including the creation in 1937 of a France department, headed by Georges Henri Rivière. The Museum’s informational and scientific component was much increased, building a clear and progressive narrative into its exhibition. It differed from the pre-surrealist, orientalist narrative by the abolition of any hierarchy or “insuperable” cultural differences and emphasis on what people from different cultures and races have in common. [ 6 ] 6. It should be borne in mind that that the non-universality and potentially repressive nature of any narratives (of narratives as such) were not recognised at that time. That recognition only emerged from work carried out in the 1970s and 1980s, in the transition to postmodernism. With that reservation, the narrative of the Musée de l'homme can be called progressive. The ethnological museum has ceased to be a collection of titillating objects. Instead, it offered clarification and made the other accessible and understandable through a detailed explanation and the creation of a universal semantic field.

4. Museology experienced a crisis in the 1970s. Large, universal narratives were now felt as repressive. It became clear that such narratives leave their source and the projections of their would-be universalism — the discursive structures of the particular society that formulated such universalism — invisible, even as the specifics of that society’s “logos” [ 7 ] 7. Here we intentionally use the term "logos" in the postmodernist-traditionalist discourse, reproducing to an extent the logic of the postmodernist critique of the universal. In this we follow the example of the Russian philosopher Alexander Dugin who gives the titles, "Logos of France", "Iranian Logos", "Latin Logos", "Logos of Turan", etc., to the books in his "Noomakhia" series. Generalising, this logic takes each civilisation or culture to have its own logos as a certain original, relatively closed and self-referential system of thought, its own system of meanings and their generation, its own discourse. And each such Logos can only be fully understood on its own terms. This idea rhymes again with the surrealist project: Guillaume Apollinaire dreamed in 1913 in his poem Zone of "Christs of another shape and another faith" ("des Christ d'une autre forme et d'une autre croyance"), testifying to the proto-postmodernist "seeds" of the Contemporary, which are scattered abundantly throughout the surrealist legacy. Following the chain of references: the influence on Alexander Dugin of French avant-garde thought of the 1920—1930s is also beyond doubt (Dugin's column in the Russia literary newspaper, Literaturnaya Gazeta, was entitled "Acephale", in a direct reference to the journal founded by Georges Bataille). remain scattered throughout the narrative and expositional structure, and even if a distancing from that society is postulated by the structure, as in the department of France at the Musée de l’homme. At issue were the invisible epistemological and hermeneutic structures that organise knowledge itself.

It was understood that the museum should be much more connected with the social life of the local community and play a greater role for that community than could be played by a brute collection of objects and repository of knowledge. In the new museology, museums were to be the servants of specific communities. In France, this need gave rise to the concept of eco-museums, developed principally by three museologists: the same Georges Henri Rivière and two representatives of the younger generation, André Desvallées and Hugues de Varine.

In 1969, the France section, Rivière’s brainchild, moved from the Musée de l’homme to a separate building where it became the Musée national des arts et traditions populaires (“Museum of Folk Arts and Traditions”, MNATP). Ten years earlier Rivière, then also director of the International Council of Museums (ICOM), had hired André Desvallées to run the museology department of the France section. Desvallées gained renown as a methodologist in the sphere of folk museums for his work in the 1960−1970s in the France section and at the MNATP, which set standards as an advanced museum institution.

In addition to its permanent exhibition the MNATP had three galleries for temporary exhibitions, which Desvallées also worked on. The main practical principles of his museology were emphasis on the “vernacular” [ 8 ] 8. A vernacular region is a territory, which the people living there separate out as a unit in their minds, regardless of administrative boundaries. Vernacular regions are less prevalent in Russia than in Europe and the USA. Examples of vernacular regions in Russia are Pomor'ye (the north coast of European Russia) and Yaroslavshchina (the area around the city of Yaroslavl'). and context dependence. Influenced by Duncan Cameron, [ 9 ] 9. Duncan F. Cameron was an outstanding 20th century Canadian museologist, one of the leaders of the new museology and developer of the museum's communicative function. Important texts by Cameron include Museum: Temple or Forum? (1971). Desvallées came to understand the museum exhibition as a communicative system with visuality and spatiality as the key features of its medium. He developed the theory of “expography”, or the technique of “writing” an exhibition as a text. According to Desvallées, this process is based on research and its ultimate aim is to establish communication with the public and convey to it the message intended by the museographer.

The impact of Desvallées on formation of the eco-museum as an institution was very great: both conceptually, by developing and putting into practice the principles of regional folk museums, and also in terms of organisation. [ 10 ] 10. In the early 1970s, Desvallées also became a senior official in the management of museums in France and established a foundation for the development of eco-museums. One example of work by that foundation is the experimental Écomusée du Creusot Montceau-les-Mines, a museum of industrial culture established in 1972. Desvallées subsequently worked on the theoretical generalisation of museological theory, introducing the term "new museology" post factum and proposing a number of other original concepts. The term “eco-museum” was proposed by Hugues de Varine at the 11th ICOM conference in 1971. It was intended that eco-museums would be the main vehicles of new principles in museology. They would serve as mirrors for the local community, both as internal mirrors, explaining to people the territory, which they themselves inhabited, and their connection with the generations who lived there before, and also as external mirrors for tourists and visitors. The key principles were the social aspect of the museum and emphasis on the tangible and intangible heritage of the community, in which the museum is created and whose identity it reflects. The aim of the eco-museum was to involve people in the process of museum creation, bringing them together around the project, making them actors in and users of their heritage, creating a community database, and thereby initiating a discussion within the community about self-reflective knowledge.

The structuralist realisation that any knowledge and narrative is a sign and part of an identity has led to the requirement that museums should be constructed by communities themselves. So it is to be left to others themselves to care for their heritage and objects. French museology has, in this, largely coincided with museology in the Anglo-Saxon countries, which began at about the same time to engage the members of First Nations and Indigineus cultures in the creation of museums representing their cultures. These practices correlate closely with the “chorological” projects of local history museums, which were developed by the Russian liberal intelligentsia in the 1910s and the first half of the 1920s. The concept of chorology (from the Greek “khōros”, plural “khōroi”, meaning “place” or “space”) is based on the idea that the space of the Earth is made up of specific “khōroi” each of which is a separate, distinctive, complex space. Chorological local history highlighted, described and identified such “khōroi” and chorological museology sought to represent them in regional and local museums. The Moscow students of Dmitry Anuchin’s school (representatives of the new geography) were particularly committed to this approach. The most notable among them was Vladimir Bogdanov, who created the Museum of the Central Industrial Region in the Soviet capital in the 1920s. However, chorological local history in Russia was subsequently reformatted to fit the Soviet Marxist mould.

In Western European the 1970s saw a return of cultural relativism associated with local identity (the same occurred at the same time in the unofficial sphere in the USSR). In French museology, this process was a dialectical development of the socially engaged project of the Musée de l’homme. But the order of the day was no longer to affirm universal human values, which were now passed over in silence, but to cultivate local communities. In the concept of the eco-museum, the progressive pathos of French ethnological humanism was combined with a post-modern deconstruction of universal narratives.

But, despite the application of new principles in community museums and particularly in various regional eco-museums, the principal ethnological museums remained as they had been, their entire exhibitions embodying knowledge structures that were already perceived as repressive. In the 1980s, the whole of ethnographic science was perceived as a way of creating a dominant narrative. And while Anglo-Saxon science traditionally recognised differences, emphasising the struggle of minority cultures for their rights, French museology insisted on universalism, egalitarianism and the equality of races and cultures. So French ethnological museums faced a paradoxical task: to dismantle universal narratives, while at the same time insisting on certain unchallengeable and specifically “French” universal values, such as tolerance and the equality of cultures. [ 11 ] 11. This reflects the paradox of postmodernism, which summons each culture to express and manifest its specificity and particularity (its non-universality), so that values previously considered universal, such as the words "Freedom, equality, fraternity" (the French national motto), had to be recognised as a tradition and specificity of French geoculture. In this context the production and upholding of universal categories is understood as a private concern of one society, its "brand" on the market of geocultural national identities. So the universal is "provincialised" (the term used by postcolonial theoretician, Dipesh Chakrabarty) and retains its pathos and claim to universality.

Under the conditions of (neo-)liberalism and a corresponding upsurge in the role of collectors in all spheres related to art, a solution was found in the “subtraction” of the repressive scientific narrative and the re-aestheticisation of ethnographic objects. In France, this process is associated with the project of Jacques Chirac (President of France from 1995 to 2007) to create the Musée du quai Branly, a vast new ethnographic museum on the banks of the Seine in Paris.

5. Chirac had been an enthusiast of eastern cultures from an early age and in 1992, as Mayor of Paris, he refused to celebrate the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ voyage, citing the crimes against other cultures, which followed upon that event. In the 1990s, during a vacation in Mauritius, Chirac met Jacques Kerchache, a collector and amateur ethnographer. A couple of years earlier, Kerchache had published a book, African Art, where he argued that, apart from, and more importantly than their ethnological value, objects of “primitive” or “first” art possess high artistic value and that these objects should be viewed through the prism of aesthetics. The story is that Kerchache was emboldened to introduce himself to the Paris Mayor after spotting his book in a photo of Chirac’s office, among the books and papers on the Mayor’s desk. Chirac told the collector that he had indeed read the book several times and was very glad to meet the author. An alliance was forged between politician and collector, which would have momentous consequences for ethnological museums in the French capital.

Chirac considered art and ethnology to be two completely different disciplines, as he emphasised in a landmark speech given in 1995 at the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle (Natural History Museum) in Paris. He and Kerchache supported the concept of “arts premiers” (“first arts”), which was anathema to the social and contextual thinking of the ethnologists of the Musée de l’homme. For them, the term “first arts” represented a return of obscurantism, since it was a descendant (albeit less harsh on the ear) of the term “primordial arts”, beloved of the Gaullist Minister of Culture, André Malraux. It should be noted, however, that a decade before Malraux gave currency to “primordial arts”, the structuralist Lévi-Strauss had taken the “human spirit” as the building block of his universal theories. The concept of “first arts” can be seen as the triumphant return of universalism to French museology, but accompanied by a re-aestheticisation of the object, which the “priests of contextualisation” found unacceptable.

Chirac and Kerchache initially wanted to reform the Musée de l’homme, but, faced with powerful opposition from its curators, they decided that it would be easier to build a new museum. In 2000 a department specialised in the “best” works of first art was created at the Pavillion des Sessions (part of the Musée du Louvre), under the management of Kerchache, and in 2006 the Paris public was presented with the highly ambitious Musée du quai Branly. The collection of the new museum consisted of works from the ethnology laboratory of the Musée de l’homme and from the Musée national des arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie (National Museum of the Arts of Africa and Oceania), enriched by 10,000 objects acquired from museums and collections, over which Kerchache had rights.

The two institutional collections, which the new museum brought together, were of quite different natures. The Museum of Africa and Oceania had been established by André Malraux in 1961 as a museum of French overseas possessions on the basis of the colonial exhibition of 1931 and was an aesthetically oriented collection. The ethnological collection of the Musée de l’homme was a highly contextualized collection, which “abstracted from” the aesthetic properties of objects.

a diaspora of forms, objects in diaspora, are, in a sense, the ideal republican model (if, by “republican”, we mean the new political mainstream, combining economic neoliberalism with cultural conservatism).

Choosing a name for the new institution presented special challenges. Chirac and Kerchache wanted to affirm cultural diversity through the universal dominance of art, but some new museological concept had to be found to express this, which would not scandalise the scientific community of museologists. Names such as “Museum of the First Arts” and “Museum of Man, the Arts and Civilisation” were considered, but the first introduced regressive terminology and hinted at a connection with the art market, while the second unjustifiably separated art from civilisation and put them in apposition. So it was decided to name the new institution after its address: Musée du quai Branly (“Museum on Branly Embankment”). Later, the name of the Museum’s creator, Jacques Chirac, was added to the title. Oddly enough, the final version successfully reflects the voluntaristic and subjective nature of the institution in the new (neo-)liberal context.

The declared goal of the Museum was cultural diversity and its creators explicitly presented it as post-colonial. Kerchache wrote in his manifesto: “Masterpieces of the entire world are born free and equal”. However, the noble task of putting the cultural diversity of the World on display was represented exclusively through art practices that were proclaimed as universal. The architect Jean Nouvel built a “temple of objects”, where the visitor, after passing through the “sacred garden” of landscape architect Gilles Clément, found him/herself in a hugely immersive space without reference points.

Scandals soon erupted around the new Museum. The architecture critic of The New York Times Michael Kimmelman described it as a “spooky jungle, […] briefly thrilling as spectacle, but brow-slappingly wrongheaded”. [ 12 ] 12. Kimmelman, M. "A Heart of Darkness in the City of Light" // The New York Times, July 2, 2006. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/02/arts/design/02k.... Date of reference: September 9, 2018. The curator of the Asian collection, Christine Hemmet, showed Kimmelman the back of a Vietnamese scarecrow, on which falling American bombs had been painted, and said that she had wanted to install a mirror to show this to the viewer, but was not permitted to do so. The director of the Museum, referring to the earlier generation of socially oriented museologists, told Kimmelman, that “the priests of contextualization are poor museographers”.

A conflict broke out between the ethnological laboratory of the Musée de l’homme, on the one hand, and Chirac and Kerchache, on the other. Bernard Dupaigne, the head of the laboratory, published a book, Le scandale des arts premiers: la véritable histoire du musée du quai Branly (“The scandal of the first arts. The true story of the Museum on the Branly Embankment”), [ 13 ] 13. Dupaigne B. Le Scandale des arts premiers. La véritable histoire du musée du quai Branly. Paris: Mille et une nuits, 2006. where he called the new museum “pharaonic” and wrote that the staff of the Musée de l’homme have nothing against the exhibition of non-Western objects as art, but are against the term “first art”, because it denies that the objects have a history or underwent changes, and treats them as “original, primary art”, which leads to a “new obscurantism”.

The museologist Alexandra Martin called the new institution the “Museum of Others”, arguing that others are represented there as others for Europe, without a past or a living present. [ 14 ] 14. Martin, A. "Quai Branly Museum and the Aesthetic of Otherness" // North Street Review: Arts and Visual Culture, 2011, December, vol. 15. pp. 53–63. https://ojs.st-andrews.ac.uk/index.php/nsr/article.... Date of reference: September 3, 2018. Bernice Murphy, head of the ICOM Ethics Committee, dubbed the new principles, manifested by the Musée du quai Branly, “regressive museology”, and the Portuguese museologist, Nélia Dias, suggested that what had happened at the museum was a “double erasure”, rubbing out both France’s colonial past and the history of the collections. [ 15 ] 15. Dias N. "Double Erasures: Rewriting the Past at the Musée du quai Branly" // Social Anthropology, 2008, October, No. 16 (3). pp. 300–311. Dias suggested that the museum had an implied political brief: it was opened at a time when France was experiencing problems with migrants, and, unable to solve problems with real people, the country had delegated this task to the museum. The mission of the Musée du quai Branly, according to Dias, was to exculpate society for its failure in dealing with the people and cultures whose objects are kept in museums dedicated to cultural diversity, so that equality in the field of art goes hand in hand with inequality in society. [ 16 ] 16. Dias N. Ibid., p. 307.

Ethnologists who kept faith with progressivist traditions perceived Chirac and Kerchache as the epitome of the Gaullist art establishment. Journalists alleged that Chirac (once nicknamed “the Bulldozer” by his political ally, Georges Pompidou) had pushed through his museum project amid nepotism, corruption and exorbitant pricing, ignoring the opinion of the scientific community and focusing only on the opinion of Kerchache, whom Bernard Dupaigne referred to as a “trader” and even a “looter”. [ 17 ] 17. Emmanuel de Roux. Le Monde, October 10, 1990 and April 14, 2000.

All in all, the Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac (to give it its full name) was seen as an attempt to create a new type of institution reflecting neoliberal ideology. Drawing on postcolonial theory, the museum proclaims cultural differences, as if proclaiming as a new kind of universalism. Kimmelman, in his damning review, cited Chirac’s declaration at the Museum’s opening that “there is no hierarchy among the arts just as there is no hierarchy among peoples”, and made the powerful retort: “No hierarchy, except that at the Pompidou Centre [the best-known Paris collection of modern and contemporary art] you find Western artists like Picasso and Pollock; at Branly, it’s Eskimos, Cameroonians and Moroccans. No hierarchy, but no commonality either. Separate but equal.” [ 18 ] 18. Kimmelman, M. "A Heart of Darkness in the City of Light" // The New York Times, July 2, 2006. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/02/arts/design/02k.... Date of reference: September 9, 2018. Indeed, this artificial division between human cultures expresses the core of neoliberal conservatism, which states: “To each his own.” Cultural divisions correspond to economic divisions, which are beneficial and desirable for the market and for the centre-right political parties that dominate the world today, notably the republican parties in France and the United States. Pluralistic universalism and assimilative universalism are quite different things.

In the new paradigm, the world is divided between, on the one hand, those who have identity and produce cultural diversity, “nailed” to their places of residence and, as a rule, poor living conditions, and, on the other hand, the few who are able to “understand” them, i.e., to consume their culture, have access to it, play with identities, proclaim universalism and have an increased appetite for everything that is other. This situation sets the stage for an interesting piece of legerdemain in respect of objects. As Octave Debary and Mélanie Roustan have written in a study, the visual experience of a visitor to the Branly museum is that of a meeting with the Other and with the absence of the Other. [ 19 ] 19. Debary, O., Roustan, M. "A Journey to the Musée du quai Branly: The Anthropology of a Visit" // Museum Anthropology, 2017, No. 40, 1, pp. 4–17. Others have disappeared, they are absent, there are no accompanying texts to explain anything about them, but their objects remain, and this unexpectedly prompts a question on the part of the visitor: why are we seeing these cultures here, what happened to them?

Objects without their creators generate a diaspora of things, or, to use John Peffer’s term, “objects in diaspora”. [ 20 ] 20. Cited in: Arndt, L. "Reversing the Burden of Proof as Postcolonial Lever" // 36 short stories. Paris: Betonsalon, 2017, pp. 65−73, 66. These objects seem to have achieved something that was not vouchsafed to their creators: they have emigrated and fitted into the Western context. The creators of these objects — certain tribes and societies — no longer exist, but the objects taken from them, which came to Europe through processes of coercive control, are here, representing their cultures. It is clear that all the theories of the last 30 years, which lend great importance and independent life to objects, are connected with the new political and economic conglomerate. A diaspora of forms, objects in diaspora, are, in a sense, the ideal republican model (if, by “republican”, we mean the new political mainstream, combining economic neoliberalism with cultural conservatism). This model brings along with it a speculative philosophy that endows things with a special agency, freeportism as an artistic style and ideology, [ 21 ] 21. See: Heidenreich, S. "Freeportism as Style and Ideology: Post-Internet and Speculative Realism" // e-flux Journal, 2016, March, No. 71. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/71/60521/freeportis... an enhanced role for collectors and, to a large extent, a postcolonial theory, which proclaims difference and is neutral towards separation.

The key question in the new situation is: do the intellectual ideologies and concepts, which have been described, offer any new progressive opportunities? The crisis of ethnographic representation in the 1980s was clear to see. A full return to the principles of contextual, “correct”, socially responsible museology is no longer possible. One sign of this is the fact that the Musée du quai Branly has proved very popular with the general public. Ethnological museology in France has passed through a series of dialectical transformations: from the unified experience of science and art (the “surprising objects” of the Trocadéro Museum) to the stripping away of the aesthetic and private (the ethnographic humanism of the Musée de l’homme), then to the removal of the universal and the return of differences, but maintaining a social mission and still excluding aestheticism (eco-museums), and finally to the return of aestheticism at the Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, whereby Paris has restored one aspect of the old Trocadéro.

Marking the opening of the Musée de l’homme in the 1930s, Michel Leiris praised the new institution as progressive, but paid tribute to the old Troca for its avoidance of didacticism and strict boundaries, a loss which he sought to remedy in the Collège de Sociologie, [ 22 ] 22. Le Collège de Sociologie (The College of Sociology) was a circle of intellectuals that existed in Paris in 1937–1939, led by Georges Bataille, Michel Leiris and Roger Caillois. Members of the circle strove to maintain the research-based and deconstructive attitude towards culture, which had been lost by the dominant art of that time (Surrealism, in particular) and by the official ethnology of the Musée de l'homme. which retained the spirit of surrealist ethnography as radical cultural criticism. Today in Paris there is a partial recreation of the Troca, in the Chirac Museum, and there is the Musée de l’homme, but neither of them achieves an integrated, critical attitude towards their own culture. The only alternative offered by Bernard Dupaigne and many other critics of the Chirac Museum is a return to contextualised exhibitions, which, let us remember, were also once seen as repressive. The Chirac Museum does not attempt cultural criticism in its permanent exhibition, but its parallel programme raises many questions and perhaps shows a way of escape from disciplinary frameworks, contextualisation and aesthetics. Interdisciplinarity and cross-culturalism are, undoubtedly, among the products of the described “republican” conglomerate. [ 23 ] 23. We aim to use the term "republican" in a universal sense, giving it a general, generic meaning. A key feature of "the republican" is the combination of a (neo-)liberal course in the economy with a moderate conservative rhetoric of distinctly traditionalist self-identification. The term emphasises the crucial link between the market and identity, including political identity, which the term "neoliberal" fails to capture. It also emphasises the fact that, over time, any significant characteristics, even revolutionary characteristics, get built into geocultural identity as a "tradition". It is important to understand that in the course of the 20th century republican rhetoric migrated from the "left" political flank and that today it is much more often used by centre-right and conservative politicians. The neoliberal agenda that is dominant in Russia today can also be called republican, although due account must be taken of the relatively greater centralised, statist component, i.e., of the Russian tradition. It may be that the new political economy has given birth to a new museum form, a form that cannot be described using exclusively old definitions without omitting precisely what is new about it.

But this does not stop us criticising the political and economic forces and processes that generated and maintain the Chirac Museum. We might propose a new concept, that of “republican museology”, the essential features of which have been described above, including a special focus on the object, as expressed most vividly at the Chirac Museum. This museology combines progressive and conservative features, postulating cultural diversity, but depriving the diversity of anything rational in common besides its possibility to produce affect in viewers. It mirrors the transformation, undergone by the republican ideal itself. Today this ideal is more likely to be the preserve of the centre-right, where market freedoms make an alliance with cultural diversity, underwritten by a conservative and post-colonial agenda, and market universalism is often left hidden. Real social problems to do with people are transferred onto objects, which are endowed with fetishistic, auraistic and subjective properties in a “total market” context. This is accompanied, in the intellectual sphere, by various speculative theories and, in the field of art, by the special role accorded to collectors and the increased importance now given to the materiality of works and practices of working with objects.

What we are faced with, overall, is the traditional problematic of French ethnology, with the issue of an other object at its centre. Hence the scale and intensity of the public debate aroused by the recent reformatting of Paris’ ethnological museums.

Translation: Ben Hooson

- The author is grateful to Maria Silina for drawing attention to the theme of French ethnological museology.

- The connections were at the level of both people and ideas. The ideologists of left-wing Eurasianism, Petr Suvchinsky and Dmitry Svyatopolk-Mirsky were primarily critics (music and literary, respectively). Hence their ability to transform Eurasianism, for the purposes of their left-wing project, from its previous status as a humanitarian scientific theory (a concept) into a percept, a conscious all-encompassing utopia, in which a general philosophical theory was supplemented by aesthetics and political activism. Its tasks in the French context — corrosive criticism of the Western cultural order and the provision of alternatives — put left-wing Eurasianism in sync with surrealism and ethnology. Suvchinsky was personally and professionally associated with many avant-garde activists, including Igor Stravinsky and André Shaeffner (an ethnologist and member of staff at the Trocadéro). For more details see: Smirnov, N. "Left-wing Eurasianism and Postcolonial Theory" // e-flux Journal, # 97, February 2019).

- Clifford, J. "On Ethnographic Surrealism" // Comparative Studies in Society and History, 1981, October, vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 539-564.

- Here we use the term "ethnology", which, in terms of its content, is closer to the French tradition. However, in the cited text Clifford ignores the traditions of self-description of French ethnology and makes use exclusively of the term "ethnography" as being more universal. So Clifford's "French ethnography" is the equivalent of our "ethnology".

- Strzygowski, J. "'Recherches sur les Arts Plastiques' et 'Histoire de L'Art'" // Documents 1, April 1929, pp. 22–26.

- It should be borne in mind that that the non-universality and potentially repressive nature of any narratives (of narratives as such) were not recognised at that time. That recognition only emerged from work carried out in the 1970s and 1980s, in the transition to postmodernism. With that reservation, the narrative of the Musée de l'homme can be called progressive.

- Here we intentionally use the term "logos" in the postmodernist-traditionalist discourse, reproducing to an extent the logic of the postmodernist critique of the universal. In this we follow the example of the Russian philosopher Alexander Dugin who gives the titles, "Logos of France", "Iranian Logos", "Latin Logos", "Logos of Turan", etc., to the books in his "Noomakhia" series. Generalising, this logic takes each civilisation or culture to have its own logos as a certain original, relatively closed and self-referential system of thought, its own system of meanings and their generation, its own discourse. And each such Logos can only be fully understood on its own terms. This idea rhymes again with the surrealist project: Guillaume Apollinaire dreamed in 1913 in his poem Zone of "Christs of another shape and another faith" ("des Christ d'une autre forme et d'une autre croyance"), testifying to the proto-postmodernist "seeds" of the Contemporary, which are scattered abundantly throughout the surrealist legacy. Following the chain of references: the influence on Alexander Dugin of French avant-garde thought of the 1920—1930s is also beyond doubt (Dugin's column in the Russia literary newspaper, Literaturnaya Gazeta, was entitled "Acephale", in a direct reference to the journal founded by Georges Bataille).

- A vernacular region is a territory, which the people living there separate out as a unit in their minds, regardless of administrative boundaries. Vernacular regions are less prevalent in Russia than in Europe and the USA. Examples of vernacular regions in Russia are Pomor'ye (the north coast of European Russia) and Yaroslavshchina (the area around the city of Yaroslavl').

- Duncan F. Cameron was an outstanding 20th century Canadian museologist, one of the leaders of the new museology and developer of the museum's communicative function. Important texts by Cameron include Museum: Temple or Forum? (1971).

- In the early 1970s, Desvallées also became a senior official in the management of museums in France and established a foundation for the development of eco-museums. One example of work by that foundation is the experimental Écomusée du Creusot Montceau-les-Mines, a museum of industrial culture established in 1972. Desvallées subsequently worked on the theoretical generalisation of museological theory, introducing the term "new museology" post factum and proposing a number of other original concepts.

- This reflects the paradox of postmodernism, which summons each culture to express and manifest its specificity and particularity (its non-universality), so that values previously considered universal, such as the words "Freedom, equality, fraternity" (the French national motto), had to be recognised as a tradition and specificity of French geoculture. In this context the production and upholding of universal categories is understood as a private concern of one society, its "brand" on the market of geocultural national identities. So the universal is "provincialised" (the term used by postcolonial theoretician, Dipesh Chakrabarty) and retains its pathos and claim to universality.

- Kimmelman, M. "A Heart of Darkness in the City of Light" // The New York Times, July 2, 2006. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/02/arts/design/02k.... Date of reference: September 9, 2018.

- Dupaigne B. Le Scandale des arts premiers. La véritable histoire du musée du quai Branly. Paris: Mille et une nuits, 2006.

- Martin, A. "Quai Branly Museum and the Aesthetic of Otherness" // North Street Review: Arts and Visual Culture, 2011, December, vol. 15. pp. 53–63. https://ojs.st-andrews.ac.uk/index.php/nsr/article.... Date of reference: September 3, 2018.

- Dias N. "Double Erasures: Rewriting the Past at the Musée du quai Branly" // Social Anthropology, 2008, October, No. 16 (3). pp. 300–311.

- Dias N. Ibid., p. 307.

- Emmanuel de Roux. Le Monde, October 10, 1990 and April 14, 2000.

- Kimmelman, M. "A Heart of Darkness in the City of Light" // The New York Times, July 2, 2006. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/02/arts/design/02k.... Date of reference: September 9, 2018.

- Debary, O., Roustan, M. "A Journey to the Musée du quai Branly: The Anthropology of a Visit" // Museum Anthropology, 2017, No. 40, 1, pp. 4–17.

- Cited in: Arndt, L. "Reversing the Burden of Proof as Postcolonial Lever" // 36 short stories. Paris: Betonsalon, 2017, pp. 65−73, 66.

- See: Heidenreich, S. "Freeportism as Style and Ideology: Post-Internet and Speculative Realism" // e-flux Journal, 2016, March, No. 71. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/71/60521/freeportis...

- Le Collège de Sociologie (The College of Sociology) was a circle of intellectuals that existed in Paris in 1937–1939, led by Georges Bataille, Michel Leiris and Roger Caillois. Members of the circle strove to maintain the research-based and deconstructive attitude towards culture, which had been lost by the dominant art of that time (Surrealism, in particular) and by the official ethnology of the Musée de l'homme.

- We aim to use the term "republican" in a universal sense, giving it a general, generic meaning. A key feature of "the republican" is the combination of a (neo-)liberal course in the economy with a moderate conservative rhetoric of distinctly traditionalist self-identification. The term emphasises the crucial link between the market and identity, including political identity, which the term "neoliberal" fails to capture. It also emphasises the fact that, over time, any significant characteristics, even revolutionary characteristics, get built into geocultural identity as a "tradition". It is important to understand that in the course of the 20th century republican rhetoric migrated from the "left" political flank and that today it is much more often used by centre-right and conservative politicians. The neoliberal agenda that is dominant in Russia today can also be called republican, although due account must be taken of the relatively greater centralised, statist component, i.e., of the Russian tradition.