museums as conflict zones

In this essay Maria Silina is conceptualizing the museum as a source of ongoing class, national, and cultural conflict, addressing important historical cases and examples of functioning of museums in contemporary society.

Museums are places that produce and expose values.

Values necessary lead to conflicts.

Museums are places of multiple conflicts.

Indeed, as James Clifford famously put it, museums are contact zones of negotiations between communities and stakeholders [ 1 ] 1. James Clifford, "Museums as Contact Zones," in Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century, Harvard University Press, 1997, pp. 188-219. . At least, ideally.

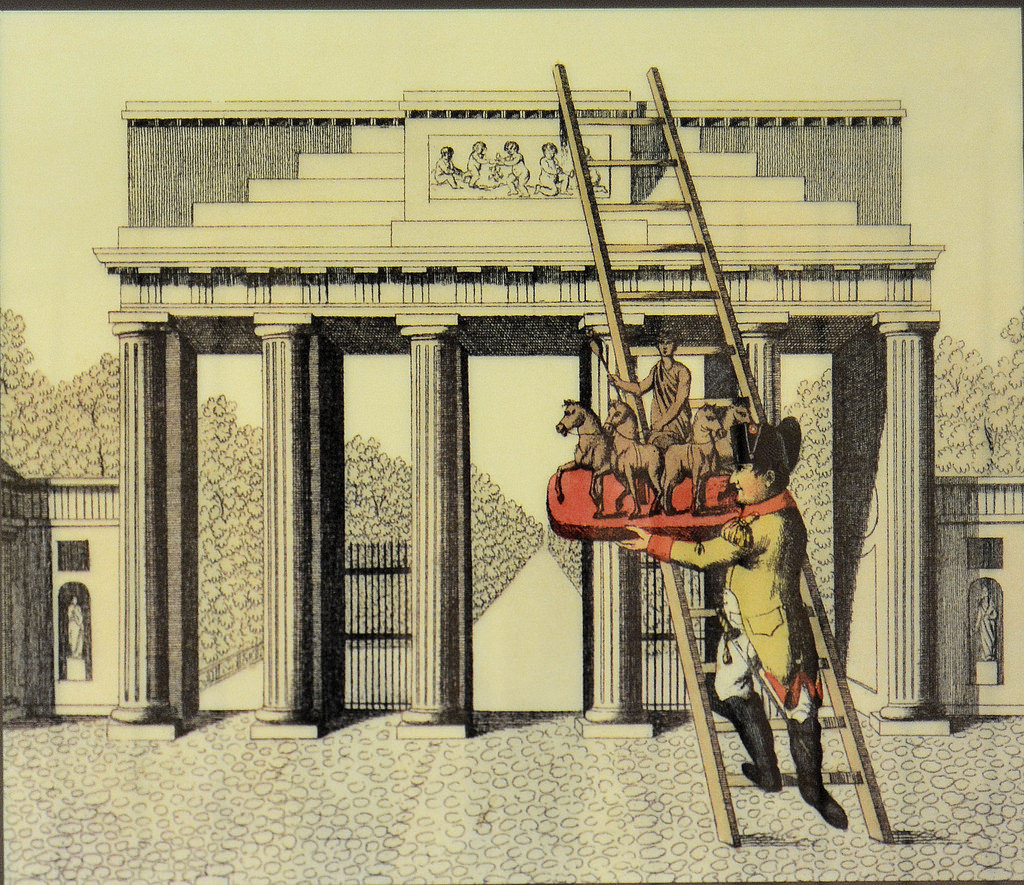

As this short essay seeks to show, for decades and even centuries museums have, in fact, been contact zones of failed negotiations. For all that time they have, in essence, avoided their true role. This approach, which views the museum as a place of crisis, lets us conceptualize the museum as a key institution in contemporary society and a source of ongoing class, national, and cultural conflict. The Louvre has, since its creation, always been the model for a modern public museum. Its collection and its function as an art museum of national glory was consolidated after Napoleon’s march through Europe in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. French authorities and troops diligently and systematically expropriated museum treasures from neighboring countries, particularly Italy and Germany, and the looted art was accumulated in the Louvre. Several European museums then followed the Louvre’s example in building their own collections. This is how the modern history of museums began: national triumph and cultural accomplishments were synergetic to tyranny and robbery and generated a tension between nations and museums that lasted for decades [ 2 ] 2. Bénédicte Savoy, "Zum Öffentlichkeitscharakter deutscher Museen im 18. Jahrhundert," in Bénédicte Savoy,, Tempel der Kunst: Die Geburt des Öffentlichen Museums in Deutschland 1701-1815, Böhlau, 2015, pp. 9-10. .

The sequence of events, initiated by Napoleon’s act of plunder, continues to our day. Several lesser-known episodes occurred at the time of the First World War. When war broke out, a number of German cultural activists set to work identifying and locating works of art that had been looted by Napoleon. In case of victory, they intended to press for the repatriation of these works. Wilhelm von Bode, a founding father of modern museology, was especially enthusiastic and active in this act of historical justice [ 3 ] 3. Christina Kott, and Bénédicte Savoy, Mars & Museum: Europäische Museen im Ersten Weltkrieg, Böhlau, 2016, p. 12. . Another museum worker, Ernst Steinmann, Director of the Bibliotheca Hertziana carried out comprehensive research into Napoleon’s looted art. For diplomatic reasons it was only published nearly a century later, in 2007 [ 4 ] 4. Christoph Roolf, "Die Forschungen des Kunsthistorikers Ernst Steinmann zum Napoleonischen Kunstraub zwischen Kulturgeschichtsschreibung, Auslandspropaganda und Kulturgutraub im Ersten Weltkrieg". Steinmann's study, Napoleons Kunstraub is available online. .

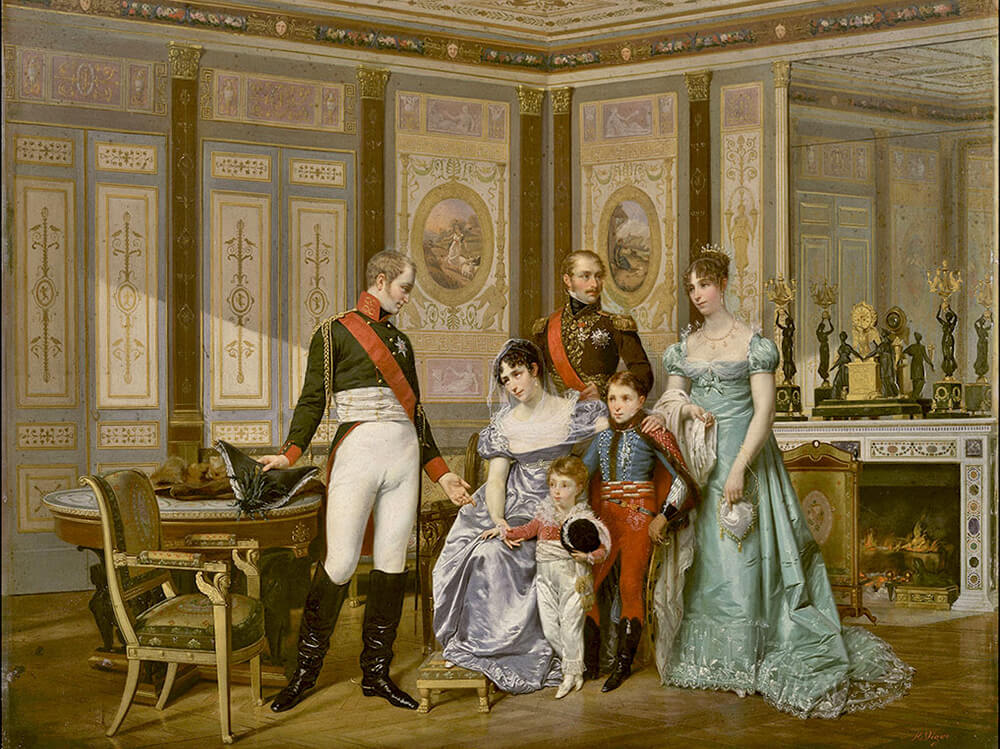

Steinmann’s archive research was the first step towards the creation of a Europe-wide map of plundered museum treasures. Demands for restitution extended even to the Russian Empire, or the country that by late 1917 had become Soviet Russia. In 1815, the Russian Emperor Alexander I purchased several paintings from the Malmaison Palace of the Empress Joséphine near Paris, which had been removed from the collection of Wilhelm VIII of Hesse-Kassel. Steinmann’s survey listed 21 paintings, originally held in Germany, which had reached St. Petersburg in this way. Rembrandt’s Descent from the Cross (1634), now a core work in the Hermitage collection, is among them.

One obvious role of museums is to “normalize” societal conflicts. Museums serve as repositories of treasures that are endangered by wars, revolutions, and other natural disasters and human conflicts [ 5 ] 5. In modern history, the practice was inaugurated after the French revolution and the foundation of the Cluny Museum. See: Dominique Poulot, "Le musée et le patrimoine : une histoire de contextes et d'origines," in Michel Allard, Jason Luckerhoff, and Anik Meunier, ed., La Muséologie, Champ de Théories et de Pratiques, Presses de L'Université du Quebec, 2012, pp. 22-35. . The Russian revolution of 1917 is an excellent example of such a process of normalization through an epic crisis.

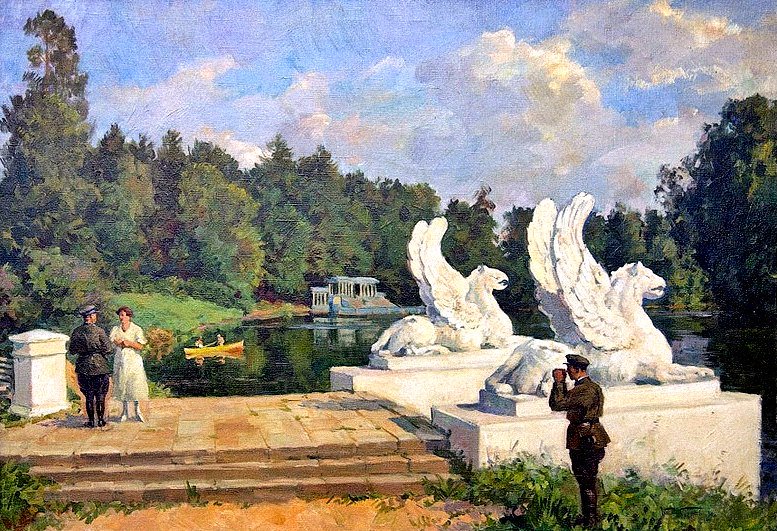

Soviet historians claimed that the Russian revolution represented a major success in restoration and heritage practice, as thousands of previously inaccessible ecclesiastical treasures, icons, decorative objects, paintings, and the magnificent interiors of former Imperial palaces and homes of the wealthy aristocracy became public property. In 1914, Russia counted 180 museums, by 1920 it had 381, and by 1928 there were 805 (the second largest number of any country in the world) [ 6 ] 6. D.A. Ravikovich, "Organizaciia muzeinogo dela v gody vosstanovleniia narodnogo hozjaistva. 1921-1925," in Ocherki istorii muzeinogo dela SSSR, Issue 6. Moscow, 1968, p. 112; O.V. Ionova, "Muzeinoe stroitelstvo v gody dovoennykh piatiletok (1928-1941 gg.)", in Ocherki istorii muzeinogo dela SSSR, Issue 5, Moscow, 1963, pp. 84-85. . This was made possible by “nationalization” – a euphemism for the forced expropriation of private and corporate property [ 7 ] 7. M.L. Kharlova, "The Nationalization of Private Collections as a State Project," Russian Studies in History, 2015, 54, 4, pp. 286-312. . Armed with revolutionary mandates, museum workers took charge of previously closed private collections and large repositories of treasures, particularly those of the Russian Orthodox Church. In a review of Western museological practice, Viktor Lazarev, a Soviet art historian of Byzantine and Medieval Russian art, called restoration the sole advanced domain in Soviet museology, thanks to the unprecedented influx of antiquities to museums after the 1917 revolution [ 8 ] 8. V. Lazarev, "Organizatsiia khudozhestvennykh muzeev na Zapade i ocherednye voprosy russkogo muzeinogo stroitelstva," Pechat i revoliutsiia, 1927, 5, p. 117. . So museum workers in Russia were, on the one hand, agents in safeguarding cultural items and, on the other hand, intruders and expropriators, armed with state decrees and mandates [ 9 ] 9. See also: Christina Kott, Préserver l'Art de l'Ennemi?: Le Patrimoine Artistique en Belgique et en France Occupées, 1914-1918, P.I.E.-P. Lang, 2006; Jonathan Blower, "Max Dvořák and Austrian Denkmalpflege at War," Journal of Art Historiography, 2009, 1. .

finally, museums are ideal places to practice the althusserian symptomatic reading centered on the absence of problems or any other kind of institutional critique. museums are places that hide societal and class conflicts.

One inevitable outcome of this “heritage protection” and creation of the Soviet museum network was the separation of objects from their original settings. The treasures of a few former Imperial and aristocratic palaces were kept where they were found (some of the palaces at Petergof and Detskoe Selo near St. Petersburg), but others, like those at Gatchina, the Paley Palace in Detskoe Selo, the Winter, Anichkov, and Shuvalov Palaces in St. Petersburg, were dispersed to museums, governmental, educational and cultural institutions, or even sold abroad [10]. The icons from the Trinity Monastery of St. Sergius in Moscow region were taken from the Orthodox Church and became the core of the icon exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery (Russia’s national gallery) [ 11 ] 11. Manuscript Department of the State Tretyakov Gallery (OR GTG) Folder 8 II, file 952, p. 152, "Correspondence of the State Tretyakov Gallery with the State Committee on the Arts in 1939". . The vagaries of war and revolution, as well as diplomatic initiatives led to major migrations of cultural objects at this time. The collection and library of the University Museum of Tartu (now Estonia) was evacuated eastward in 1915 in Nizhny Novgorod then in 1918 to Voronezh. After Estonia declared its independence, the country’s museum workers sought the return of the University collection and set to work on creation of a united museum catalogue (the work remains incomplete today) [12]. Ukraine and Poland also initiated a process of restitution of museum and cultural items under the Riga Peace Treaty of 1921, signed at the end of Soviet-Polish War. Ukraine was unsuccessful in obtaining restitution of its museum collections [ 13 ] 13. A. V'jalec', "Svіt maє pochuti," Pam'jatki Ukraїni, 1994, 1-2. For the extended bibliography see: http://www.archives.gov.ua/Archives/dis-EastEur.php. , while Poland pursued negotiations at the highest level until the eve of the Second World War (from 1921 until 1937) [14]. The displacement of cultural treasures creates a special ambiguity in the functioning of museums, calling into question their role as untouchable containers of authenticity.

The most striking and far-reaching action of isolating objects from their national and cultural settings is undoubtedly the colonial expropriation of cultural goods in the 19th and 20th centuries. The issue was recently highlighted by Emmanuel Macron, the President of France, who in autumn 2017 called for a process of restitution of Africa’s looted heritage. A year later, in November 2018, a state-commissioned report, entitled “Toward a New Relational Ethics” was published by Bénédicte Savoy, the leading European museologist and Felwine Sarr, a Senegalese scholar and cultural activist. Restitution requests, led by Ethiopia and Nigeria, date from the 1960s, but have drawn little attention until today. According to the Savoy-Sarr report, the British Museum holds 69,000 objects from Africa, the Weltmuseum in Vienna has 37,000, the soon-to-open Humboldt Forum in Berlin lists 75,000 and the Musée du quai Branly in Paris has 70,000. Meanwhile, as of 2007, all the museums on the African continent have no more than 3000 objects [ 15 ] 15. Bénédicte Savoy, Felwine Sarr, "Restituer le Patrimoine africain: vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle", Rapport remis au Président de la République, Emmanuel Macron, le 23 novembre 2018, p. 12. . The report is radical in its assumptions. It calls for a restitution process based on the assumption that all kinds of displacement of objects from the African continent during the colonial era (particularly from 1885 to 1960), including military trophies, objects brought back from scientific missions and expeditions of all kinds, as well as special gifts should be treated in the context of colonial mobilization and exploitation of the economy, politics, and culture of African countries [ 16 ] 16. Savoy, Sarr, Vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle, pp. 43-51. .

The state and museum authorities today generally acknowledge that many museum collections were accumulated in dubious ways. When the legality of ownership is put in question or contested, they often respond in an idealist perspective, citing moral and cultural considerations. Anti-restitution strategies vary from assertions of the “universality” of Africa’s heritage to the alleged incapacity of African countries to collect and safeguard their heritage

[ 17 ]

17. Barbara Loundou, "Restitution du patrimoine culturel africain". Interview with Marie-Cécile Zinsou. Africanews.

, A popular counter strategy is to champion the creation of new “universal” museums. One of the most ambitious initiatives of this kind is led by Berlin museums, which plan to open the Humboldt Forum in Berlin — a hyper-universal museum, which will amalgamate collections from the city’s state museums, including the Ethnologisches Museum and the Museum für Asiatische Kunst. The concept was put forward in 2002 in the well-known Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums, signed by the heads of major state museums in North American and Europe. The second part of the Declaration is worth citing in full (with some minor omissions): “The universal admiration for ancient civilizations would not be so deeply established today were it not for the influence exercised by the artifacts of these cultures, widely available to an international public in major museums. Indeed, the sculpture of classical Greece, to take but one example, is an excellent illustration of this point and of the importance of public collecting.

<…> Calls to repatriate objects that have belonged to museum collections for many years have become an important issue for museums. Although each case has to be judged individually, we should acknowledge that museums serve not just the citizens of one nation but the people of every nation. Museums are agents in the development of culture, whose mission is to foster knowledge by a continuous process of reinterpretation. Each object contributes to that process. To narrow the focus of museums whose collections are diverse and multifaceted would therefore be a disservice to all visitors”

[ 18 ]

18. "Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums", ICOM news, 2002, 1.

.

The Humboldt Forum in Berlin, due to open in 2019, promotes itself as just such a “place for all”, likening its concept to that of the old Kunstkammer — a collection of art and marvels (usually the privilege of royal or wealthy personages) where “objects from local and foreign cultures were divided into the categories of nature (naturalia), science (scientifica), and art (artificialia)” [ 19 ] 19. The Humboldt Forum official website: https://www.humboldtforum.com/en/pages/humboldt-forum. . In this perspective educational goals and the spectacular diversity of objects overshadow the problematic of any restitution claims.

Alongside assertion of the universalist and normalizing objectives of museums, some institutions are attempting more nuanced strategies to deflect restitution claims. One initiative by the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (a participant in the Humboldt project) is particularly intriguing. In 2017, the Staatliche Museen launched a funding program addressed to recent immigrants from Syria and Iran, who would be trained as volunteer museum guides for the Near East collection. This project promotes socially meaningful actions like mapping local immigrant culture and legacy in a metropole, engaging local immigrants and inviting 20−25 people to work with their national art while gently avoiding any questions of restitution [ 20 ] 20. Official website of the Museum: https://www.smb.museum/en/museums-institutions/museum-fuer-islamische-kunst/collection-research/research-cooperation/multaka.html. . The British Museum, another fervent defender of universal values of art [ 21 ] 21. The dramatic and detailed inquiry on the Elgin marbles, perhaps the most notorious case of looted art in modern history, can be found here: William St. Clair, "Imperial Appropriations of the Parthenon," in John Merryman, ed., Imperialism, Art and Restitution. London: Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 65-97. , which has been under a barrage of restitution claims from Greece in recent decades, has followed the Berlin initiative [ 22 ] 22. Ploy Radford, "Oxford museums train refugees as tour guides and community curators," The Art Newspaper. .

Finally, museums are ideal places to practice the Althusserian symptomatic reading centered on the absence of problems or any other kind of institutional critique [ 23 ] 23. Louis Althusser, Lire le Capital, Tome 1 & 2, with Étienne Balibar, Roger Establet, Pierre Macherey, and Jacques Rancière, Paris, 1965. . Museums are places that hide societal and class conflicts.

Tellingly, today, it is mostly artists themselves and small museums which have been willing to subject underrepresentation in museums to critical scrutiny. The Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts has added labels to works in the classical interior of the portrait gallery of respected citizens of the United States [ 24 ] 24. Maria Garcia, "At The Worcester Art Museum, New Signs Tell Visitors Which Early American Subjects Benefited From Slavery". , telling visitors “which early American subjects benefited from slavery”, while the Baltimore Museum has sold works by established, mostly male artists in order to acquire works by underrepresented artists [ 25 ] 25. Julia Halperin, "The Baltimore Museum Sold Art to Acquire Work by Underrepresented Artists. Here's What It Bought—and Why It's Only the Beginning". . Canadian museums have taken some steps to readdress normativity of the colonial gaze by renaming paintings. So, for example, Emily Carr’s work, Indian Church (1929), is now exhibited under the title Church at Yuquot Village [ 26 ] 26. "Renaming of Emily Carr painting spurs debate about reconciliation in art". .

The #Metoo movement, which burst into the mass media and cultural world in early 2017, has encouraged redefinition and reframing of the persistently patriarchal and “grands hommes” strategies of museum, as well as addressing neglect of human rights violations by artists. Michelle Hartney recently intervened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York with a series of labels that tell a neglected story behind famous paintings by such artists as Paul Gauguin, Pablo Picasso, and Balthus. The text placed by Hartney next to Paul Gauguin’s Two Tahitian Women (1899) cites a comment by the feminist author, Roxanne Gay: “We can no longer worship at the altar of creative genius while ignoring the price all too often paid for that genius. In truth, we should have learned this lesson long ago, but we have a cultural fascination with creative and powerful men who are also ‘mercurial’ or ‘volatile,’ with men who behave badly” [ 27 ] 27. Sarah Cascone, "'Museums Almost Infantilize Viewers': A Guerrilla Artist Puts Up Her Own Wall Labels at the Met to Expose Male Artists' Bad Behavior". . The labels were quickly removed from the museum.

Another case — that of the video by Beyoncé and Jay-Z shot in the Louvre, which went viral in 2018 — is especially important for grasping the twofold image of the modern museum as an open-to-all institution promoting cultural accomplishments and a successful enterprise based on capitalist productivity. It provoked heated debates about the acceptability of filming a pop-music video in a major museum and the message behind the oeuvre of American celebrities. The artists wanted to critically reframe the absence of black history and culture in museums, an action to be read in the context of the Decolonize this Place initiative. But what the debate set off by the video showed most clearly was the scale and depth of belief in the museum as a place of art and culture, which must not be “endangered” by pop culture. Interestingly, the video has also revealed much about the managerial strategies of the Louvre, a museum that, according to hundreds of social network commentaries and posts, is still perceived as an untouchable and elitist sanctuary for white, eurocentric culture. In reality, the Louvre has recently taken unprecedented steps to market and rent out its “sacred spaces” to all sorts of commercial activity, attracting wealthy corporations and Hollywood giants to make use of its halls [ 28 ] 28. Jason Farago, "At the Louvre, Beyoncé and Jay-Z Are Both Outsiders and Heirs". .

This synergy of museums and the marketing industry is increasingly prevalent. Urban museums have become highly visible and controversial agents of the hyper-and overproduction of cultural goods and commercialized public spaces. “Artwashing” and “gentrification” are important keywords that describe museums as agents of crisis in a context of societal disparities (museums are also tellingly described as “brandscape spots” and “mass tourist attractions”). The Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and Displacement — a coalition of affinity groups in Los Angeles [ 29 ] 29. Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/BHAAADCoalition/. — is leading an anti-gentrification war in the US city: “What the neighborhood needs”, the groups insist, “is more affordable housing, and residential services such as grocery stores and laundromats” and not museums and art galleries for a privileged few [ 30 ] 30. Carolina A. Miranda, "The art gallery exodus from Boyle Heights and why more anti-gentrification battles loom on the horizon". . Numerous studies have shown at museums tend to be integrated into exclusive cultural districts and “museum islands”, conglomerates of pure (consumerist) culture segregated from social facilities [ 31 ] 31. The literature on direct impact on gentrification and the art sector are ubiquitous: Sharon Zukin, Loft Living: Culture and Capital in Urban Change, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982; D. Ley "Artist, Aestheticisation and the Field of Gentrification," Urban Studies, 2003, 40, 12, pp. 2527-2544; Jesus-Pedro Lorente, "Museums of contemporary art in a changing urban culture. Persistence and transformation of historical patterns" in Susanne Janssen, ed., Trends and Strategies in the Arts and Cultural Industries. Barjesteh Van Waalwijk Van Doorn, 2001. .

Recent exposés of the role of museums in urban social erasure as well as other controversial aspects of museum life (the irregular or unlawful way in which national collections were amassed, museums that were created thanks to war and revolution, as well as hidden social and cultural conflicts behind museum displays) make the crisis angle of museum functionality highly thought-provoking. They demonstrate the embeddedness of museums in the state ideological apparatus and the successful institutional enterprise of modern national regimes. Museums as creations of nationalism, idealism, and the class-agenda of Western culture will always be containers or vehicles of conflict. This elusive and paradoxical situation is well described by Donald Preziosi, who wrote that “the seeming luxury, marginality, or even disposability of the museum may be read in fact as the very mark of its totalizing achievement” [32].

- James Clifford, "Museums as Contact Zones," in Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century, Harvard University Press, 1997, pp. 188-219.

- Bénédicte Savoy, "Zum Öffentlichkeitscharakter deutscher Museen im 18. Jahrhundert," in Bénédicte Savoy,, Tempel der Kunst: Die Geburt des Öffentlichen Museums in Deutschland 1701-1815, Böhlau, 2015, pp. 9-10.

- Christina Kott, and Bénédicte Savoy, Mars & Museum: Europäische Museen im Ersten Weltkrieg, Böhlau, 2016, p. 12.

- Christoph Roolf, "Die Forschungen des Kunsthistorikers Ernst Steinmann zum Napoleonischen Kunstraub zwischen Kulturgeschichtsschreibung, Auslandspropaganda und Kulturgutraub im Ersten Weltkrieg". Steinmann's study, Napoleons Kunstraub is available online.

- In modern history, the practice was inaugurated after the French revolution and the foundation of the Cluny Museum. See: Dominique Poulot, "Le musée et le patrimoine : une histoire de contextes et d'origines," in Michel Allard, Jason Luckerhoff, and Anik Meunier, ed., La Muséologie, Champ de Théories et de Pratiques, Presses de L'Université du Quebec, 2012, pp. 22-35.

- D.A. Ravikovich, "Organizaciia muzeinogo dela v gody vosstanovleniia narodnogo hozjaistva. 1921-1925," in Ocherki istorii muzeinogo dela SSSR, Issue 6. Moscow, 1968, p. 112; O.V. Ionova, "Muzeinoe stroitelstvo v gody dovoennykh piatiletok (1928-1941 gg.)", in Ocherki istorii muzeinogo dela SSSR, Issue 5, Moscow, 1963, pp. 84-85.

- M.L. Kharlova, "The Nationalization of Private Collections as a State Project," Russian Studies in History, 2015, 54, 4, pp. 286-312.

- V. Lazarev, "Organizatsiia khudozhestvennykh muzeev na Zapade i ocherednye voprosy russkogo muzeinogo stroitelstva," Pechat i revoliutsiia, 1927, 5, p. 117.

- See also: Christina Kott, Préserver l'Art de l'Ennemi?: Le Patrimoine Artistique en Belgique et en France Occupées, 1914-1918, P.I.E.-P. Lang, 2006; Jonathan Blower, "Max Dvořák and Austrian Denkmalpflege at War," Journal of Art Historiography, 2009, 1.

- F.I. Shmit, "Muzeinoe delo. Voprosy ekspozitsii" in F.I. Shmit, Izbrannoe. Iskusstvo: Problemy teorii i istorii. St. Petersburg, Tsentr gumanitarnykh initsiativ, 2012, p. 707.

- Manuscript Department of the State Tretyakov Gallery (OR GTG) Folder 8 II, file 952, p. 152, "Correspondence of the State Tretyakov Gallery with the State Committee on the Arts in 1939".

- Jaanika Anderson, "Das Kunstmuseum der Universitaet Tartu vor, waehrend und nach dem ersten Weltkrieg," in Mars & Museum, pp. 201-211.

- A. V'jalec', "Svіt maє pochuti," Pam'jatki Ukraїni, 1994, 1-2. For the extended bibliography see: http://www.archives.gov.ua/Archives/dis-EastEur.php.

- Ewa Manikowska, "National versus Universal? The restitution debate between Poland and Soviet Russia after the Riga Peace Treaty (1921)" in U. Grossmann, ed., The Challenge of the Object, Germanisches Nationalmuseum 2013, 4, pp. 1360-1364.

- Bénédicte Savoy, Felwine Sarr, "Restituer le Patrimoine africain: vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle", Rapport remis au Président de la République, Emmanuel Macron, le 23 novembre 2018, p. 12.

- Savoy, Sarr, Vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle, pp. 43-51.

- Barbara Loundou, "Restitution du patrimoine culturel africain". Interview with Marie-Cécile Zinsou. Africanews.

- "Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums", ICOM news, 2002, 1.

- The Humboldt Forum official website: https://www.humboldtforum.com/en/pages/humboldt-forum.

- Official website of the Museum: https://www.smb.museum/en/museums-institutions/museum-fuer-islamische-kunst/collection-research/research-cooperation/multaka.html.

- The dramatic and detailed inquiry on the Elgin marbles, perhaps the most notorious case of looted art in modern history, can be found here: William St. Clair, "Imperial Appropriations of the Parthenon," in John Merryman, ed., Imperialism, Art and Restitution. London: Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 65-97.

- Ploy Radford, "Oxford museums train refugees as tour guides and community curators," The Art Newspaper.

- Louis Althusser, Lire le Capital, Tome 1 & 2, with Étienne Balibar, Roger Establet, Pierre Macherey, and Jacques Rancière, Paris, 1965.

- Maria Garcia, "At The Worcester Art Museum, New Signs Tell Visitors Which Early American Subjects Benefited From Slavery".

- Julia Halperin, "The Baltimore Museum Sold Art to Acquire Work by Underrepresented Artists. Here's What It Bought—and Why It's Only the Beginning".

- "Renaming of Emily Carr painting spurs debate about reconciliation in art".

- Sarah Cascone, "'Museums Almost Infantilize Viewers': A Guerrilla Artist Puts Up Her Own Wall Labels at the Met to Expose Male Artists' Bad Behavior".

- Jason Farago, "At the Louvre, Beyoncé and Jay-Z Are Both Outsiders and Heirs".

- Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/BHAAADCoalition/.

- Carolina A. Miranda, "The art gallery exodus from Boyle Heights and why more anti-gentrification battles loom on the horizon".

- The literature on direct impact on gentrification and the art sector are ubiquitous: Sharon Zukin, Loft Living: Culture and Capital in Urban Change, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982; D. Ley "Artist, Aestheticisation and the Field of Gentrification," Urban Studies, 2003, 40, 12, pp. 2527-2544; Jesus-Pedro Lorente, "Museums of contemporary art in a changing urban culture. Persistence and transformation of historical patterns" in Susanne Janssen, ed., Trends and Strategies in the Arts and Cultural Industries. Barjesteh Van Waalwijk Van Doorn, 2001.

- Donald Preziosi, "Collecting/Museum" in Robert S. Nelson and Richard Schiff ed., Critical Terms for Art History, University of Chicago Press, 2003, p. 408.