re-contextualizing traditional artworks: marxist objects and soviet museums in the 1920s and 1930s

Maria Silina’s text reflects upon original ways of displaying art objects, which were developed in Soviet Russia in the late 1920s and early 1930s, bringing to attention the specific approach of early Soviet museologists to the objecthood of artworks — their materiality and physical palpability as artefacts of class culture.

Status of museum objects today, their shifting meaning in different context, their functions in museum narration, are of crucial importance to artists and museum practitioners today. Recent years have seen a wave of landmark museum restorations and updating of the manner in which collections are displayed. Scholars have joined the debate by re-reading museum displays and exhibitions of the classical modernist era in order to offer a more nuanced understanding of modern European culture [ 1 ] 1. See for example the review of a recent book on Alexander Dorner. .

Until recently, Western art historical scholarship relied strongly on Formalism, but today, thanks to the new material turn, material semiotics (“actor-network theory”), and renewed interest in psychophysiology and the influence of experimental aesthetics in early modernism (focused on bodily experiences, physical perception, etc.), we are beginning to recognize the materiality of modernist objects and reassess conventions in art history.

As many critics observe, in the era of blockbuster exhibitions and globalized, digitalized itinerant shows, paintings and other museum objects are increasingly de-objectified. This process is driven by digital processing of museum collections, their re-arrangement and representation on the Web. However, recent studies have shown that digital images of museum objects are themselves objectified and are a certain kind of object [ 2 ] 2. Haidy Geismar. Museum Object Lessons for the Digital Age. London: UCL Press, 2018, p. 17. . Moreover, the public has entered into highly complex relationships with museum objects thanks to social network behavior patterns. This is most apparent in such phenomena as “Instagrammable” and immersion museums and blockbuster shows with “selfie moments”, which museums deliberately create/construct in order to make the museum visit more attractive and interactive.

Because of these developments, now is an excellent time to re-approach the art historical and museological conventions of the modernist era by looking at the surprisingly flexible and polyvalent relations between the public and the way it sees visual entities or the way it uses the materiality of objects to create visual narratives in social networks.

The following text is a revised version of a conference talk for the workshop “L’histoire de l’art et les objets” held by the Deutsches Forum für Kunstgeschichte, Paris, 31 May 2018.

In the 20th century, museology not only shaped a radical conceptual difference between objects and paintings but also attempted to overcome this difference in the museum display. More specifically, museology of the interwar period, not only in Russia but all over Europe, was dedicated to possible ways of identifying the work of art and its boundaries: how does an artwork differs from an everyday object, is it more advantageous to display each type of art separately or to display different types together in order to achieve a more intuitive idea of art history, and how was the question of art periodization to be approached? [ 3 ] 3. Frank Matthias Kammel, "Neuorganisation unserer Museen oder vom Prüfstein, an dem sich die Geister scheiden: eine museumspolitische Debatte aus dem Jahre 1927", Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen, N.F. 34 (1992), pp. 121–136; François Poncelet, "Regards actuels sur la muséographie d'entre-deux-guerres", CeROArt [Online], 2 (2008). The valorization of formalist features of objects (colors, shapes, texture, etc.) was one of the new options, as was an approach that showed the development of styles or cultures from the ornaments of primitive peoples to higher forms of abstraction in the non-figurative compositions of modern art.

In this short overview, I will talk about an original way of displaying art objects, which was developed in Soviet Russia in the late 1920s and early 1930s. The “Marxist exhibition” is an exemplary case of modernist attempts to synthesize a developmental approach to museum display with a Marxist approach to art as an ideological industry exemplified in certain types of objects. The Marxist exhibitions of the 1920s and 30s are attracting the attention of scholars today by virtue of their radical and thought-provoking pre-conceptual attempts to reconsider hierarchies and the ritualized spaces of contemporary art museums [ 4 ] 4. Masha Chlenova, "Soviet Museology During the Cultural Revolution: An Educational Turn, 1928 – 1933", Histoire@Politique, №33, September-December 2017 [Online: www.histoire-politique.fr]. . As I will try to show in this article, attention to the objecthood of paintings — their materiality and physical palpability as artefacts of class culture, — which was so important for the early Soviet museologists, prefigured new ways of approaching paintings in artistic and art historical practice. Descendants of his approach include such museum initiatives as the Decolonize This Place movement, which seeks to show the material/ritual reality of museologically isolated objects that were (at least some of them) unlawfully taken from their natural settings, the #Metoo movement that reveals patriarchic violence and the abuse of power behind established and widely respected art iconography of the past, the display of autochthone traditional objects in the museums of Canada, New Zealand, and Australia, etc. [ 5 ] 5. Bénédicte Savoy. Die Provenienz der Kultur. Von der Trauer des Verlusts zum universalen Menschheitserbe. Berlin: Matthes & Seitz, 2018. .

My focus, then, is museology in Soviet Russia in the 1920s and the 1930s, a period of huge change in the wake of the Russian Revolution of 1917. The Revolution triggered a radical reorganization of the country’s museum network and the nationalization of private collections. These reforms, in turn, demanded a systematic reclassification of artworks and museum objects. I will deal first with two distinct types of museum that appeared immediately after the 1917 Revolution in order to give an idea how the pair of concepts, “the visual arts” and “the art object”, were treated in Russia in the 1920s and I will then give attention to attempts to amalgamate two concepts of art objects and artworks — as material objects and as illusionistic surfaces.

The first type of museum was run by artists and emerged in Moscow and Petersburg as early as 1919. These were museums of living art, i.e. of contemporary art made by living artists. My prime example is the Museum of Painterly Culture in Moscow, which exhibited innovative works by artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Vladimir Tatlin, Alexander Rodchenko and others. Like many other iconoclast artists of the interwar period, Russian avant-gardists took a dim view of traditional, museums, which they considered to be store-houses for old, overrated bric-à-brac. Artists and theoreticians of the avant-garde such as Boris Arvatov and Osip Brik, wrote articles and manifestoes that cast a critical eye on the dominance of easel painting in contemporary European art. Easel painting was judged to be a form of art that had become dominant in European capitalist society. It was criticized as fetishistic, as supplying commodified objects to adorn the living rooms and private galleries of the aristocracy and bourgeoisie. Paintings, as Arvatov wrote, were instrumentalized in economic and cultural exchange and shaped the standard type of European classical art museum, which was a picture gallery [ 6 ] 6. Boris Arvatov. Iskusstvo i proizvodstvo [Art and Production]. Moscow, 1926. . The new museums of living art were regarded primarily as research laboratories, which would advance the search for new artistic forms and study the evolution of visual forms.

Paradoxically, in view of this avant-garde stance, the exhibition of the Museum of Painterly Culture consisted exclusively of easel paintings. However, the artists brought modernist and formalist principles to the display of their works. Instead of following a chronological order or basing the display on artistic concepts or styles, artworks were shown according to formalist principles of contrast and the manner of representation of the objects depicted. The works were divided into those that painted objects plain and those that depicted volumes. So paintings were regarded primarily as illusionistic surfaces. This approach was intended to intensify the ability of viewers to comprehend the art and not to be misled by names or subjects. The early avant-garde concept of a contemporary museum and of how to display art objects was remarkably straigtforward: the visual arts were equivalent to paintings, which were to be perceived visually.

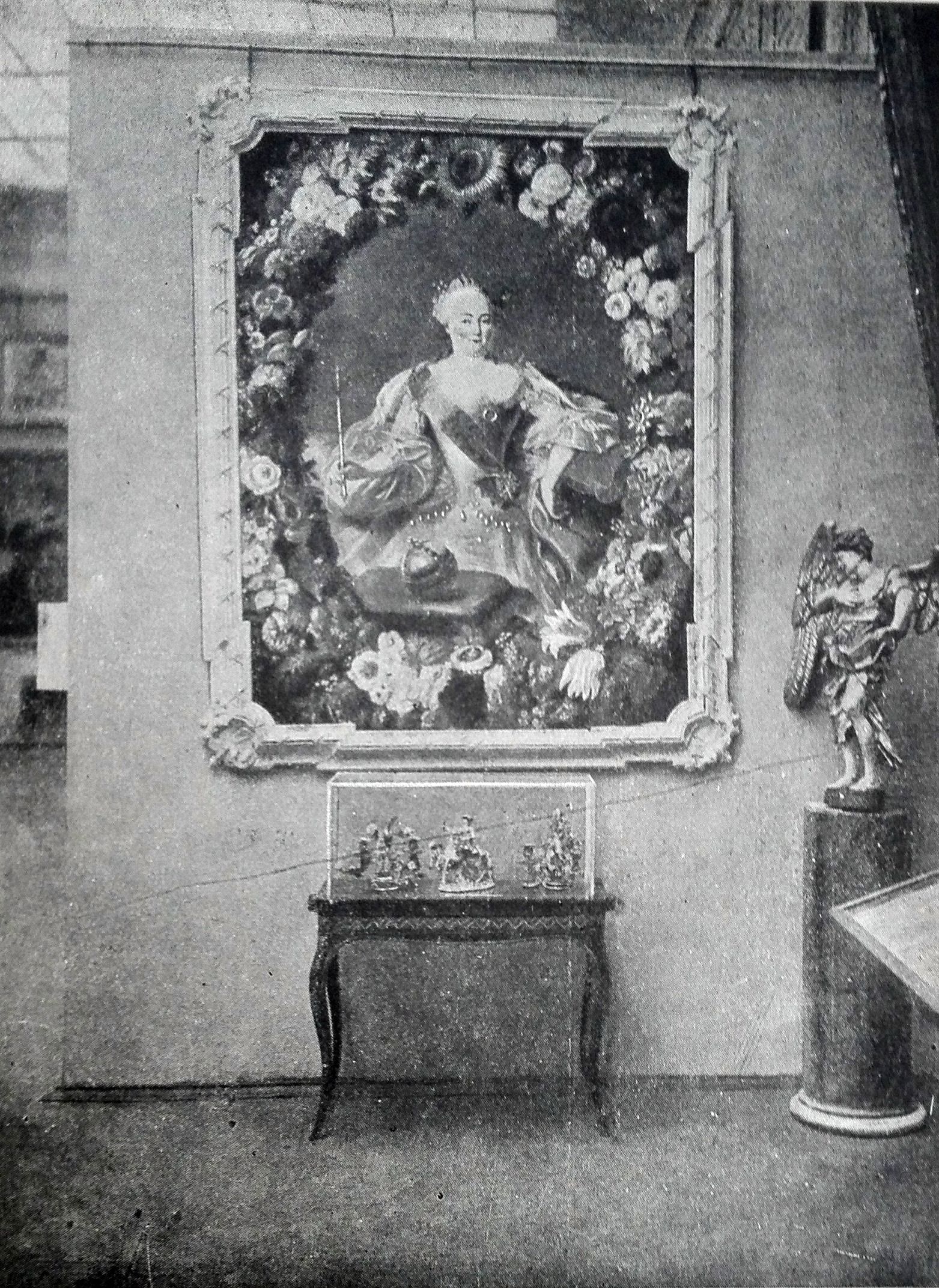

The second type of art museum in early Soviet Russia was the so-called “proletarian museum” or “didactic museum”. The idea in this case was to display artworks as beautiful objects in beautiful interiors, disregarding any art historical classifications (applied arts were exhibited alongside paintings and furniture).

A network of such museums emerged soon after the 1917 Revolution. Their exhibits were nationalized goods from the collections and homes of the former Russian bourgeoisie and aristocracy and they often used those former homes as their premises. Their primary purpose was to give an overall sense of art, beauty and cultural variety to uneducated visitors, especially those from previously marginalized groups (peasants, women, the proletariat), using a compare-and-contrast principle to give very basic ideas of what the work of art is. The exhibitions did not follow any special or new art historical classifications but were supposed to give a general idea of a past epoch or culture, and to convey a sense of beauty and preciousness of the artwork. The choice of exhibits was usually dictated by the nature of the premises where the museum was located and there was no division into decorative, utilitarian, or art objects. Proletarian museums (also called “museums of daily life”) proliferated across the Soviet Union in the years after 1917, conserving original settings in the villas and châteaux of the ousted Russian aristocracy. The concept was of a synthetic milieu that would emotionally charge the viewer by the stylistic unity and the richness of the interior. Museum workers strove to create a special auratic atmosphere to emotionally engage visitors. They did not aspire to create art history museums. Their numerous precious art objects and paintings of high quality were regarded primarily as heritage objects of cultural and historical significance.

Proletarian museums faced a barrage of criticism from Marxist museologists in the 1920s, as they inherited all the sins of the old-fashioned Kunstkammer with its uncritical and amateur approach to museum display and the history of culture.

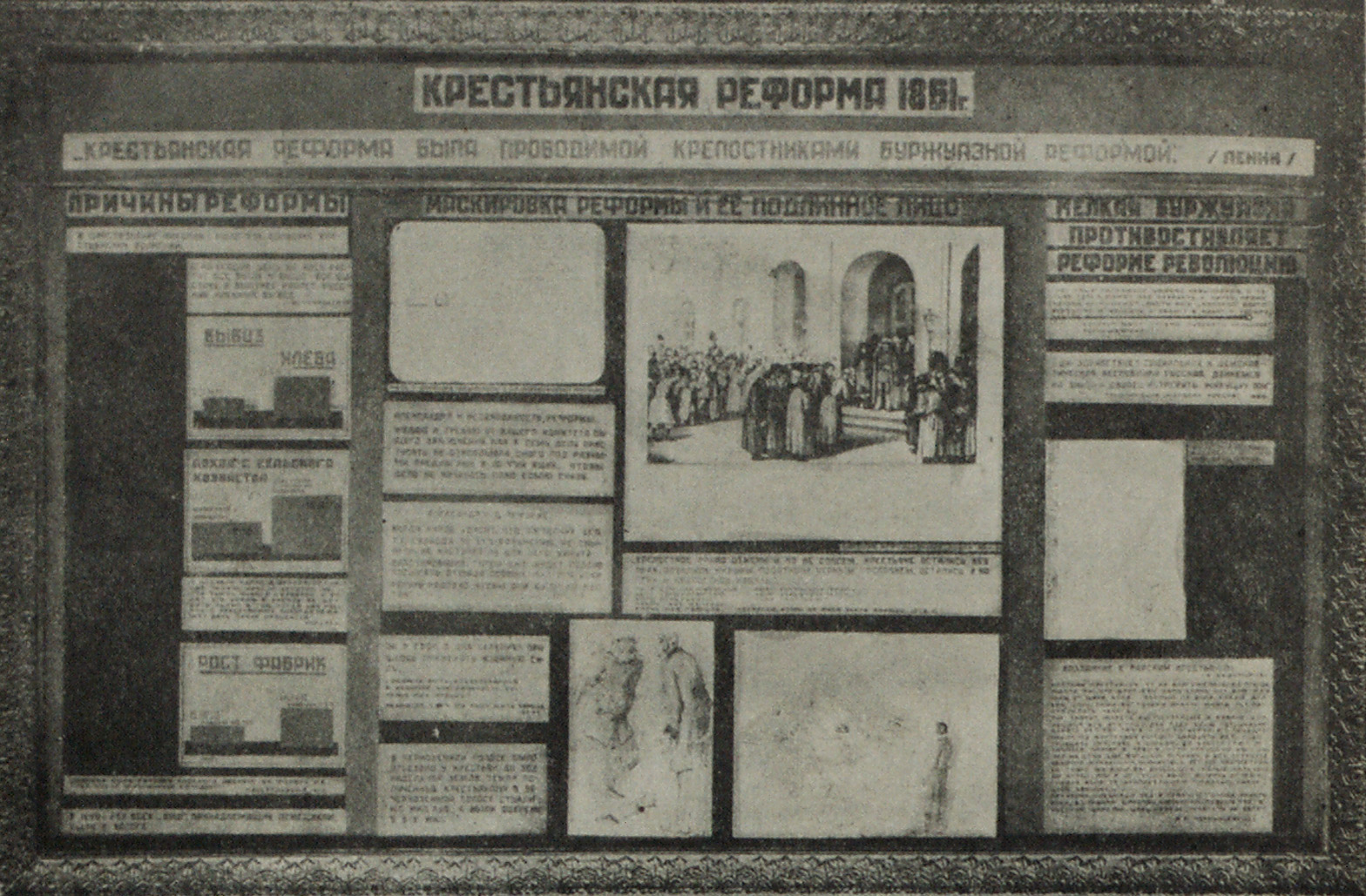

By the end of the 1920s, the two extremes represented by the Museum of Painterly Culture and proletarian museums had been reconciled in a synthesis: formalist art historical categories of pure visuality merged with the concept of historical and cultural narration to produce so-called “Marxist exhibitions”, which flourished in a relatively short period at the end of the 1920s and in the early 1930s. They were related to European museological concepts of that time, with their increasing emphasis on the educational and social functions of museums [ 7 ] 7. The prominent French museologist, Henri Rivière, visited Soviet Russia in the 1930s and was captivated by its museums and the role they played in society: "I'm not talking just about the museums, which are human, profound and fertile, but of the manner of life, the social concept. ... We'll talk more about it in Paris. But what a joy for me to find here in reality the museums, of which I had dreamt, of which I had laboriously sketched a theory in recent months. My themes of museums that accumulate, gather, select and make a synthesis are close to the museums I find here; a more precise and definite vocabulary comes to my assistance." Gradhiva, №1, Fall 1986, p. 26. [translated from French]. , but also to the specific Socialist objectives of narrating history in terms of class struggle, educating visitors to think critically about the legacy of past (non-Socialist) cultures.

The key concept of Marxist exhibitions was to show exhibits, whether paintings or decorative objects, as products of ideology. According to Marx, art and culture were superstructures of the economic relations that exist in society. So art and culture reflect those relations and the permanent class struggle that determines them. Art was seen as an ideological tool for winning dominance and power in society.

What was a Marxist exhibition supposed to look like?

It aimed to represent art history as the history of class struggle and treated artworks as commodified and instrumentalized objects in the process of class struggle for economic and cultural dominance. Any art — paintings, applied objects, advertising, amateur and naïve art — was the creation of a certain, class-defined Weltanschauung [ 8 ] 8. Alexei Fedorov-Davydov, "Fifteen years of Museum Building in the USSR", [1932]. Archive of the Russian Academy of Science. The Communist Academy files. Folder 358, box 2, file 404, p. 117. . Such was the vision of the Russian art historian and art critic Alexei Fedorov-Davydov for the future of all Soviet art museums. He meticulously elaborated the theory and practice of Marxist exhibition in art museums and implemented it at the National Picture Gallery in Moscow — the Tretyakov Gallery.

For Fedorov-Davydov, the first task was to define the dominant type of art in any epoch. In the struggle for economic and cultural dominance, the privileged class of the time (the aristocracy, the bourgeoisie, etc.) created its dominant type of art and its own style — sculpture in Antiquity, murals in the Middle Ages, etc.

Next, any Marxist exposition is a stylistic one. In his own museum practice, Fedorov-Davydov rearranged the exhibition of Russian art of the 18th and the 19th — 20th centuries at the Tretyakov Gallery to highlight the progression from applied art to easel paintings. The ornaments shown in the rococo display were meant to critically reveal the ideology of that era — the high society of bon vivants and their luxurious and superficial façon de vivre. The contemporary art section featured der Wille zur Abstraktion as the Weltanschauung of Modernism. Paintings were classified according to their visual qualities and they were arranged to show the development of formal/visual elements: lines, color, textures etc., following the model of the Museum of Painterly Culture.

there were two main strategies for treating traditional religious objects in a critical way: the objects were exhibited as fetishes; and their material nature or subject matter was emphasized in order to de-mystify them.

However, stylistic rearrangement was not enough. Paintings were to be presented in a historical development illustrating class struggle. Easel paintings, the dominant art type of the 19th and 20th centuries, were not only grouped by styles, but also contextualized by other types of objects and documents (statistics of economic development, applied art and furniture) to give a full picture of the epoch. In the Tretyakov Gallery, classical portraits of the Tsarist aristocracy were placed among documents and the everyday objects of peasants in a juxtaposition that critically reframed the message of the paintings. The idea was to show how art and the beauty of artworks had been instrumentalized by the aristocracy, bourgeoisie, etc., but also to underline the crucial economic and hence cultural difference in the lifestyles of rich and poor and their mutual influence. Fedorov-Davydov was the first to exhibit mass-produced goods such as cigarette boxes, popular postcards and printed advertisements alongside outstanding easel paintings of the same era.

Paintings and artworks were extensively commented by explanatory texts as well as by slogans and quotations to help visitors to grasp the main idea of each epoch and period. The use of periodization was unmatched by any other museum classification of the time [ 9 ] 9. Marxist exhibitions and their originality were highlighted at the most important European museological event at the Conférence internationale d'études – Architecture et aménagement des musées d'art held in 1934 in Madrid by the Office International des Musées. They were also extensively reported in journals (for example Informations mensuelles, 1934, №12, pp. 11–13). . Instead of conventional art historical periods such as baroque, classicism, art nouveau, etc., periods were based on economic formations. So the 18th century in Europe was called “the period of disintegration of feudal relations”, the 19th century was the period of “industrial capitalism”, etc.

The new approach to display raised a host of methodological questions. Perhaps the most urgent of them was: how could the poor quality of peasant art be reframed to emphasize the class-driven development of art and diversity of the cultural landscape in Russia. In Marxist exhibitions, the objects of everyday life were not treated as equal to painting, but only served to emphasize the historical and cultural context of an epoch. The potential for mixed messages was very great and invited criticism from all quarters. Some practitioners criticized these displays for treating paintings as illustrations, objectifying paintings and belittling their artistic value. Also, when less sensitive curators than Fedorov-Davydov took up his idea, the result was often a Kunstkammer instead of an art historical exhibition.

Classically trained museologists found the Marxist exhibition be too chaotic, unclear, overladen with texts, explanations and allusions, the effect of which was often the opposite of that intended. To give one example: a painting of a poor peasant girl sewing was juxtaposed with a richly adorned handkerchief, made by an anonymous peasant for her master. As observers noticed, many of the workers who visited the gallery were most impressed by the high quality of the handkerchief, produced in prerevolutionary times, and said aloud that such quality could not be achieved today.

Conservative museum workers and Communist Party museum advisors were scandalized by methods that radically changed the relationship between object and subject, opening a Pandora’s box of interpretations and perceptions of classical paintings. Art museum spaces had suddenly become places of intense encounters, where critically reframed objects provoked class-driven feelings and reactions of rage, disgust, cultural dissonance, etc. By the 1930s the new orthodoxy of the Party was increasingly uncomfortable with such revolutionary methods and there was growing pressure for a return to the old orthodoxy of ritualized art museums, full of silence and sterility.

A major part of Russia’s artistic legacy was religious in nature and this posed another huge problem for the organization of museums after 1917. Soviet political leaders, museum workers, and visual artists faced the challenging task of introducing militant atheism to an overtly religious country. The majority of the population were Orthodox Christians, and there were substantial Muslim, Jewish, and Buddhist communities. What was to be done with the wealth of sacral objects collected in churches, mosques, and Lamaist temples?

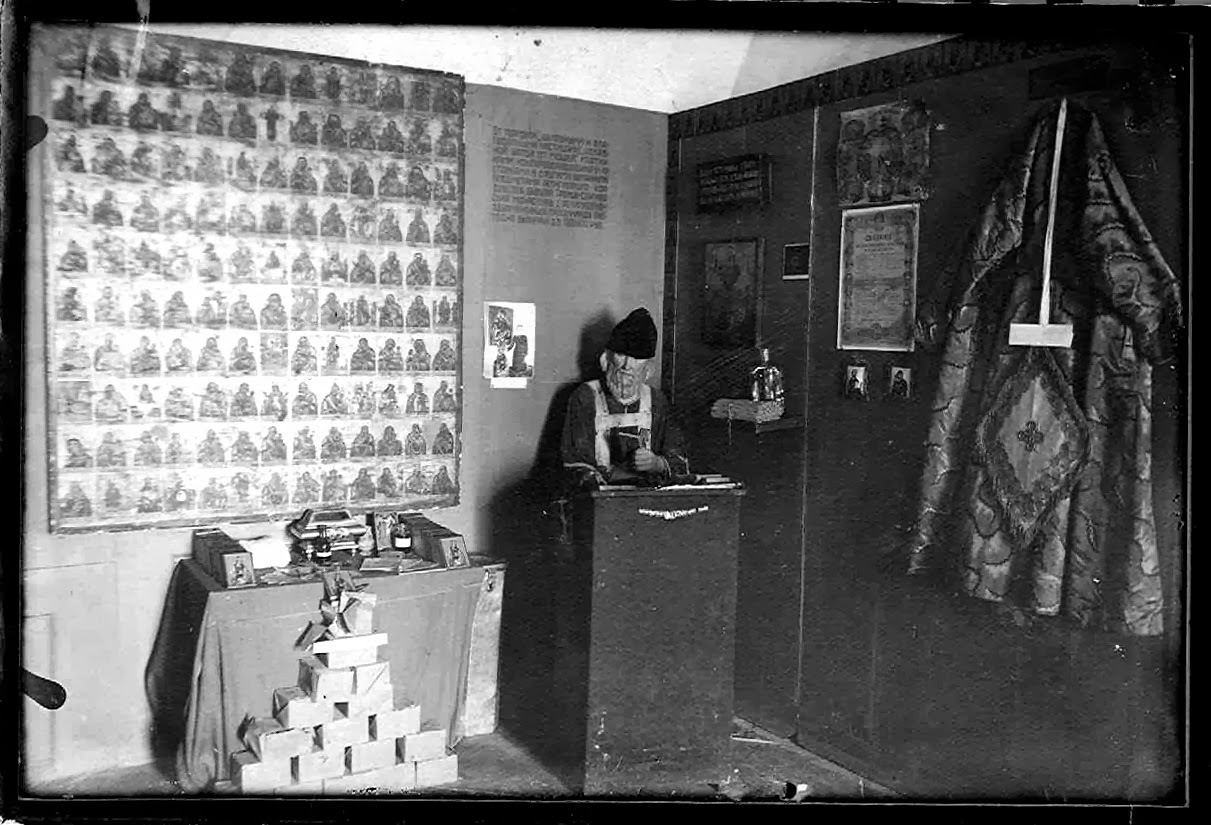

Initially, Soviet museologists exhibited religious objects in a classical way: as brilliantly made decorative objects. But such displays were harshly criticized for the lack of a critical agenda and the undesirable effect that they might have on proletarian visitors.

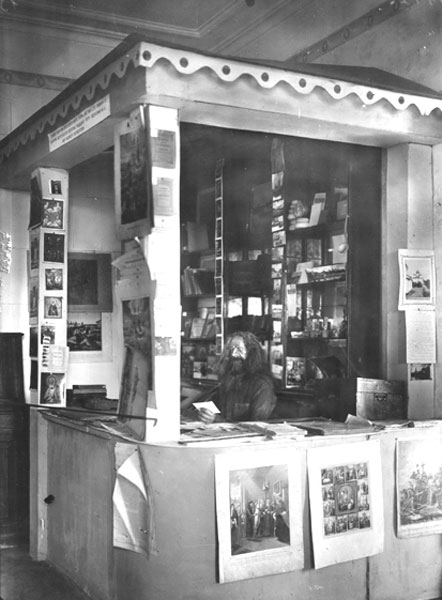

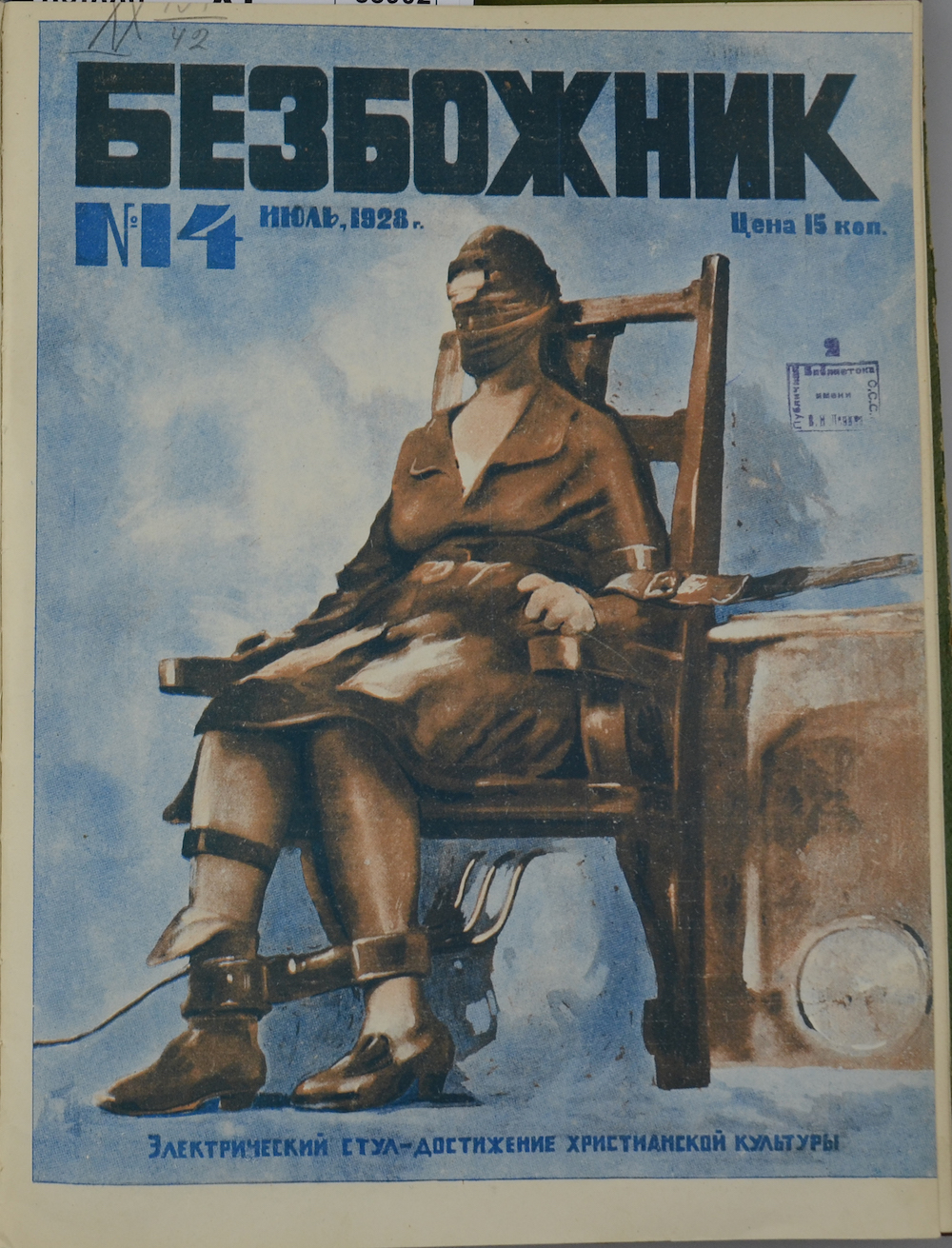

From the mid-1920s, militant activists launched a campaign to re-contextualize sacral art objects, books, clerical garments, and icons in favor of a class-struggle agenda. Cultural workers and art historians were to emphasize the imperialist, colonial, chauvinist, and anti-scientific nature of any religion. Numerous exhibitions, itinerant shows, mass demonstrations, graphic production, caricatures, postcards, and theatrical shows were launched to drive this point home. These Soviet experiments anticipated key aspects of Conceptualism and institutional critique, where artists use their works and performances to critically reframe established hierarchies in museum and art historical practice.

There were two main strategies for treating traditional religious objects in a critical way: the objects were exhibited as fetishes; and their material nature or subject matter was emphasized in order to de-mystify them. Artistic aspects of the objects were made to play a denunciatory role and the borders between art historical, cultural and political space became vague. I will offer an overview of the most popular early-Soviet museological approaches to the exhibition of religious objects.

Exhibition organizers aimed to provoke strong feelings against these creations of the religious past by presenting them as fetishes. Richly adorned clerical garments were exhibited as clues to high-class, elite and bourgeois culture and were compared to the clothing and surroundings of the working-class milieu. Black and white photographs of workers’ barracks were shown in striking contrast to the costly and luxurious everyday objects of the clergy. Even the size of alms baskets was presented as an indication of the financial interests and wealth of the Church.

Subject matter was shown in a way that critically re-contextualized sacral objects and artworks. Icon subjects depicting violent scenes served as proofs of the militaristic, chauvinist, anti-feminist, and hypocritical nature of Christianity. Another popular approach was to present the Ecclesia Militans in a new way: as an institution that supports war. This was especially effective, since memories of the Great War of 1914 — 1918 were still fresh. It was shown how portraits of saints and religious paintings, prayers and processions were mobilized in support of the War, and these images were set alongside newspaper reports, paintings of anti-war artists showing soldiers in the trenches and statistics of deaths (the War and Church exhibition of 1931 in Moscow is perhaps the best example of this). The contrast between the splendour of ritual and the uncanny pictures of human blood and death left viewers in shock. Newspapers and museum visitors books were full of bitter comments, evoked by such comparisons.

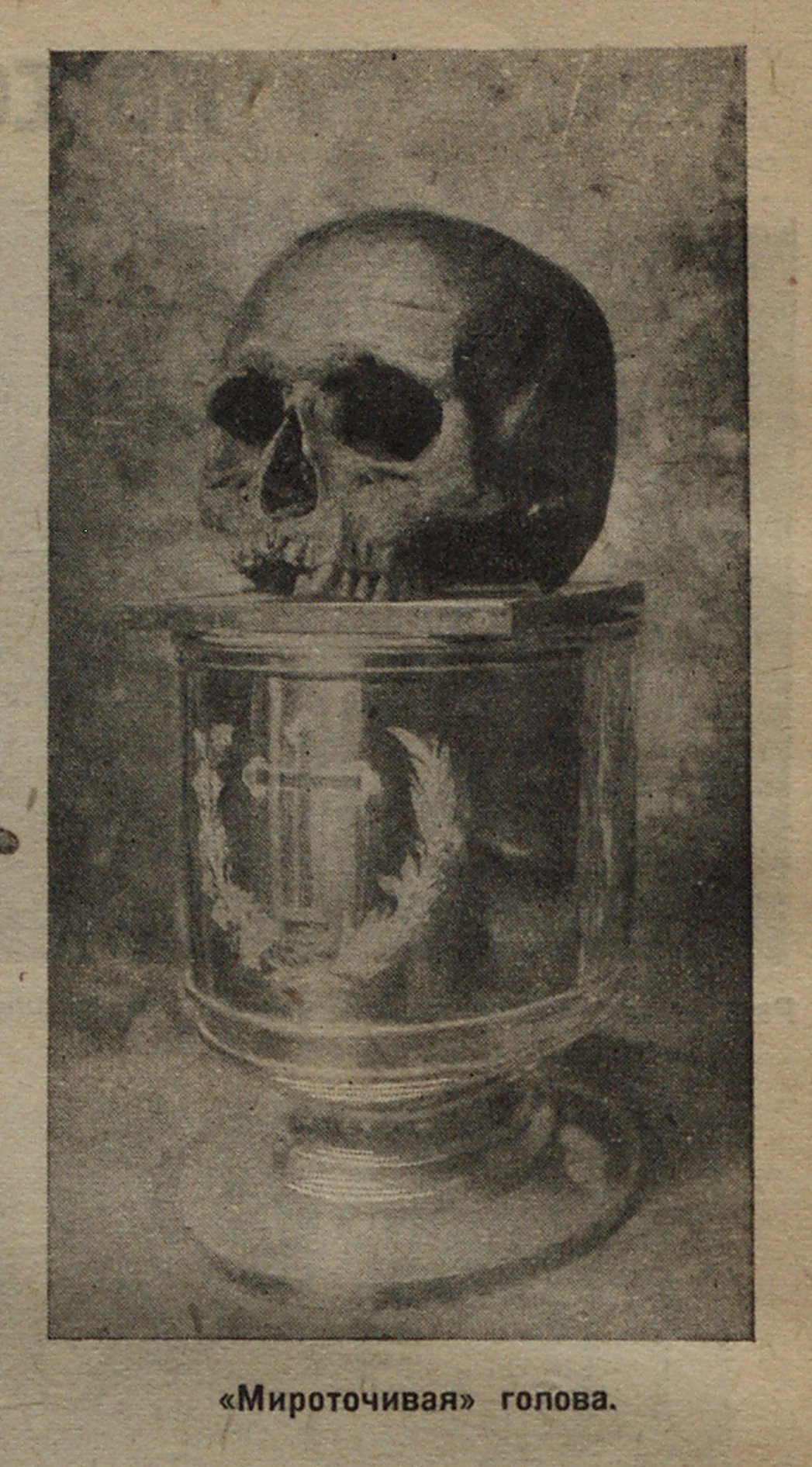

Another powerful way of rearranging religious subjects was to debunk myths and evoke disgust. There were shows that exposed the human remains of saints together with the remains of rats, dogs, or deceased vagrants, emphasizing the material and mortal nature of all human life against the pretence of immortality offered by the Church.

The materiality and tactile nature of religious statuary was also used as evidence of the anti-social nature of the Church. Statues with visible traces of the contact of millions of worshippers were shown with short scientific extracts about bacteria and immunity, inspiring nausea at the potential harm, which these rituals might have caused. And Soviet museum workers organized special events to emphasize the deceitful universe of the Church, using microscopes to show the existence of organisms that Holy Scriptures ignore, and giving lectures on the illogical, irrational, and degenerative development of certain animal species in order to debunk the harmonious account of the universe, which is found in the Bible.

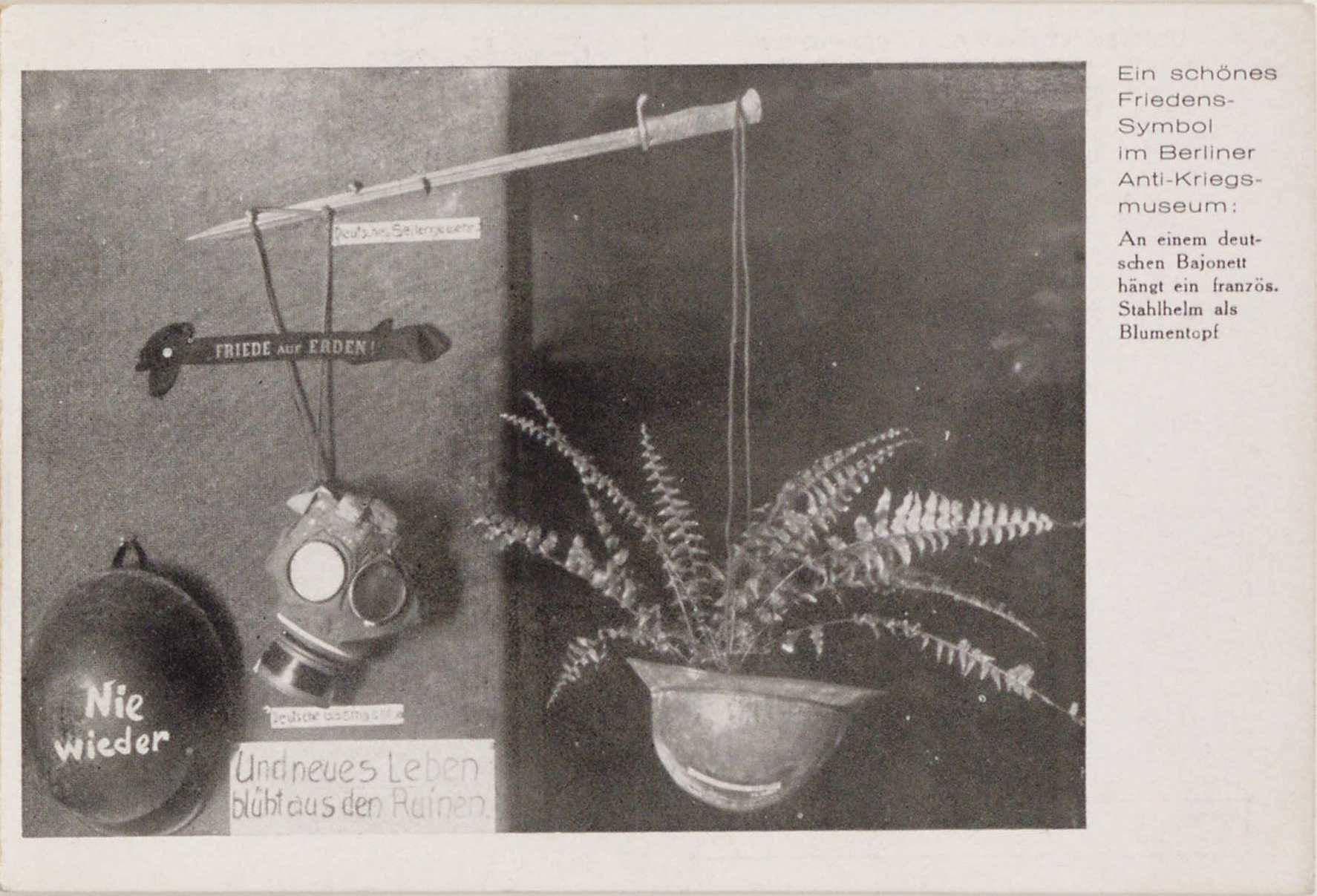

These aspects of Soviet practice in the 1920s and 1930s were part of a broader trend throughout Europe at the time towards denunciatory and critical exhibitions. Critical juxtaposition of visual arts and various objects (sacral, decorative, ready-made) was used and conceptualized in museum displays. Germany’s Anti-Kriegs-Museum (1925 – 1933) and the Anti-Colonial exhibition by French Surrealists in Paris in 1931 are obvious examples. European exhibition organizers sometimes used Soviet materials, photocollages, and diagrams for their own purposes [ 10 ] 10. Adam Jolles. The Curatorial Avant-garde: Surrealism and Exhibition Practice in France, 1925 – 1941. University Park, 2013, pp. 57–92. Museum and cultural collaboration with German cultural and political organizations is mentioned, for example, in B.P. Kandidov, "Put borby" [Path of Struggle] in Sovetskoe gosudarstvo i religia 1918 – 1938, dokumenti iz archiva Gosudarstvennogo muzeia istorii religii [The Soviet State and Religion 1918 – 1938. Documents from the State Archive of the History of Religion]. St. Petersburg, 2012, p. 287. .

By the mid-1930s, Soviet museologists had turned away from critical, class-divided representations of paintings and religious objects in favour of a more conservative, non-critical portrayal of religious objects and paintings as a national heritage, which the proletariat should admire for its high artistic quality. But, as shown by their influence on the critical agenda of contemporary museums today, the early modernist museological experiments in Soviet Russia set important precedents by making new conceptual connections between artworks, decorative and utilitarian objects, and by changing the way in which all these items were classified in art history.

These critical methods of showing the class-driven, colonial, patriarchal, etc., nature of traditional domains of European culture are now broadly accepted in museums of ethnography, civil rights, etc. Since the late 1980s, the Ethnographic Museum in Neuchâtel proposes a radical reframing of objects collected by colonial powers. Another museum on another continent, the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum uses straightforward juxtapositions of art works and archival documents on the real life of black people at the time when these art works were created [ 11 ] 11. https://mobile.nytimes.com/2017/12/18/arts/design/jackson-mississippi-civil-rights-museum-medgar-evers.htm. .

- See for example the review of a recent book on Alexander Dorner.

- Haidy Geismar. Museum Object Lessons for the Digital Age. London: UCL Press, 2018, p. 17.

- Frank Matthias Kammel, "Neuorganisation unserer Museen oder vom Prüfstein, an dem sich die Geister scheiden: eine museumspolitische Debatte aus dem Jahre 1927", Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen, N.F. 34 (1992), pp. 121–136; François Poncelet, "Regards actuels sur la muséographie d'entre-deux-guerres", CeROArt [Online], 2 (2008).

- Masha Chlenova, "Soviet Museology During the Cultural Revolution: An Educational Turn, 1928 – 1933", Histoire@Politique, №33, September-December 2017 [Online: www.histoire-politique.fr].

- Bénédicte Savoy. Die Provenienz der Kultur. Von der Trauer des Verlusts zum universalen Menschheitserbe. Berlin: Matthes & Seitz, 2018.

- Boris Arvatov. Iskusstvo i proizvodstvo [Art and Production]. Moscow, 1926.

- The prominent French museologist, Henri Rivière, visited Soviet Russia in the 1930s and was captivated by its museums and the role they played in society: "I'm not talking just about the museums, which are human, profound and fertile, but of the manner of life, the social concept. ... We'll talk more about it in Paris. But what a joy for me to find here in reality the museums, of which I had dreamt, of which I had laboriously sketched a theory in recent months. My themes of museums that accumulate, gather, select and make a synthesis are close to the museums I find here; a more precise and definite vocabulary comes to my assistance." Gradhiva, №1, Fall 1986, p. 26. [translated from French].

- Alexei Fedorov-Davydov, "Fifteen years of Museum Building in the USSR", [1932]. Archive of the Russian Academy of Science. The Communist Academy files. Folder 358, box 2, file 404, p. 117.

- Marxist exhibitions and their originality were highlighted at the most important European museological event at the Conférence internationale d'études – Architecture et aménagement des musées d'art held in 1934 in Madrid by the Office International des Musées. They were also extensively reported in journals (for example Informations mensuelles, 1934, №12, pp. 11–13).

- Adam Jolles. The Curatorial Avant-garde: Surrealism and Exhibition Practice in France, 1925 – 1941. University Park, 2013, pp. 57–92. Museum and cultural collaboration with German cultural and political organizations is mentioned, for example, in B.P. Kandidov, "Put borby" [Path of Struggle] in Sovetskoe gosudarstvo i religia 1918 – 1938, dokumenti iz archiva Gosudarstvennogo muzeia istorii religii [The Soviet State and Religion 1918 – 1938. Documents from the State Archive of the History of Religion]. St. Petersburg, 2012, p. 287.

- https://mobile.nytimes.com/2017/12/18/arts/design/jackson-mississippi-civil-rights-museum-medgar-evers.htm.