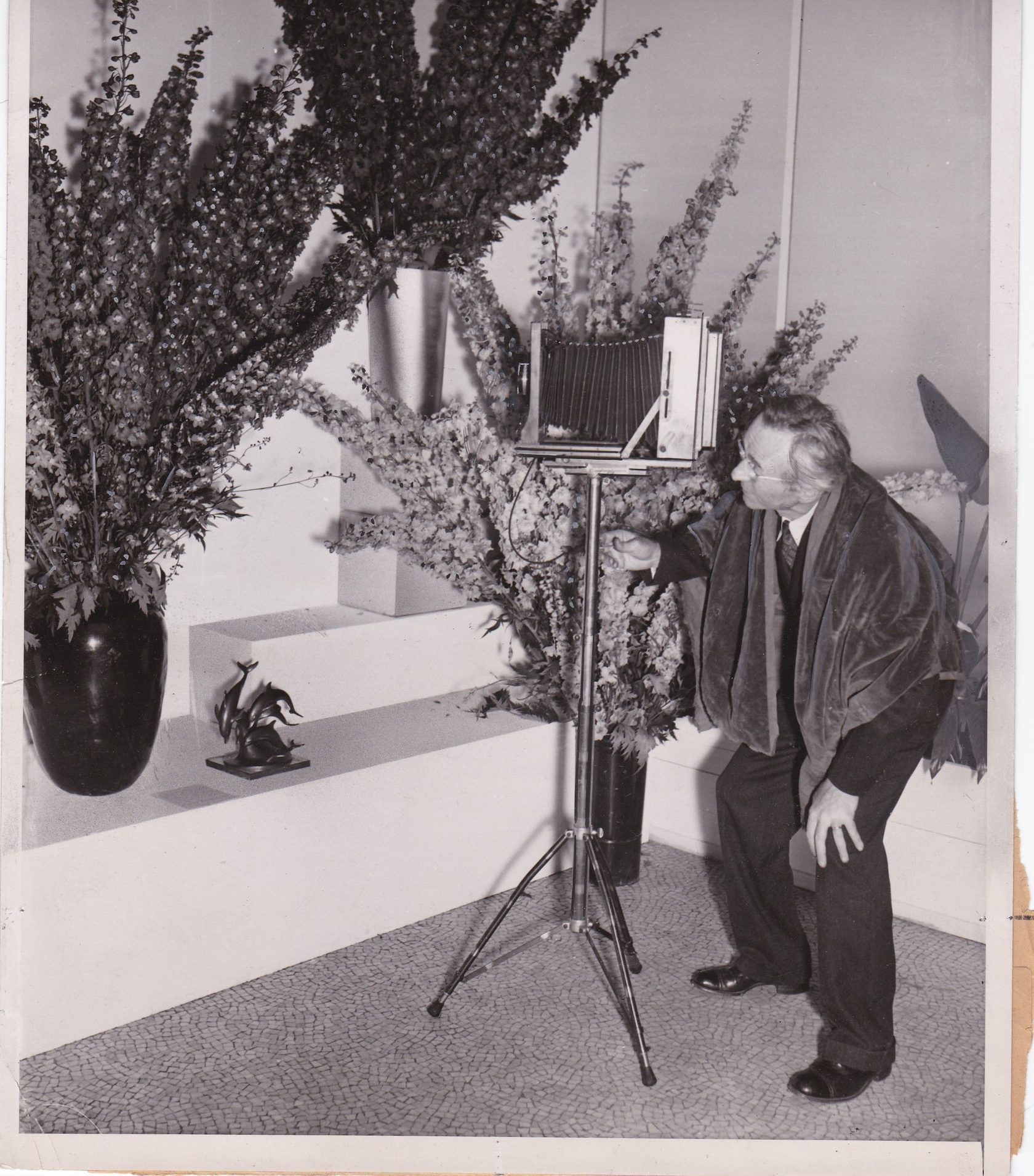

moma: edward steichen’s delphiniums, 1936

The series of retrospective reviews of MoMA exhibitions continues with Andrey Shental’s text on Edward Steichen’s Delphiniums (1936). The artist and art critic reviews the exhibition where artist and horticulturist, Edward Steichen, displayed his delphinium varieties. Andrey Shental uses the exhibition as a departure point to explore in a specific way the notion of hybridity as an inherent quality of the post-medium era and look back at its initial meaning of intersection of the natural and the artificial.

The concept of a hybrid (as well as its derivatives: hybridity, hybrid, hybridization) is used so widely today that it becomes synonymous with everything contemporary. Hybrid wars, hybrid regimes, hybrid cars. The word also takes on an evaluative meaning when hybridization is viewed as an effective weapon of progressive politics, disrupting endogamy, breaking down fixed identities and producing an infinite number of differences. Conservative critics, on the other hand, describe hybridization as a homogenizing practice that erases local traditions and conventions. So on one hand there is the ideology of fundamentalism, essentialism, purism and awesome invariants: purity, solidity, ineluctability. On the other, there are the processes of pidginization, creolization, glocalization and various transitional states (liminality, volatility, plasticity, fluidity). Toxic masculinity, white supremacism and identity politics are taking a beating from assemblages, prostheses and cyborgs.

In contemporary art, art hybridization is understood as something innovative or high-tech and is associated primarily with science art. Hybrid arts are a subculture that includes formalist practices of interactive design using high technologies with the prefixes “info”, “bio”, “nano”, “cogno”. Today, though, in the postmedium condition, any art is hybrid, because there is no longer a division into specific mediums (painting, sculpture, etc.), and the fundamentally interdisciplinary nature of art implies the inclusion of any research themes, openness to other areas knowledge and an invitation to experts from other fields to join in.

Perhaps the hybrid nature of art should be understood in a completely different way, putting the emphasis on its “non-artificial” character – a continuum between the natural and the cultural. By linking the concept of hybridity with its original biological meaning, we can reassess the very “artificiality”, “artistry” and “technicality” of art. Our start point will be a half-forgotten, almost curious exhibition project.

In 1936, MoMA presented some extraordinary “works” by Edward Steichen, one of the foremost modernist photographers. The exhibition, organized in two stages, displayed to the public varieties of delphiniums, which were the result of 26 years of work selecting and cross-breeding flowers on ten acres of land in Connecticut. In the first stage the public were shown “true blue or pure blue colors, and the fog and mist shades”, followed in the second stage by huge spike-shaped plants from one to two metres tall. The exhibition press release clarified: “To avoid confusion, it should be noted that the actual delphiniums will be shown in the Museum – not paintings or photographs of them. It will be a ‘personal appearance’ of the flowers themselves.”

At that time the public still viewed the activities of MoMA with much scepticism (especially after the Machine Art exhibition), and the Museum legitimized the non-traditional objects of its latest show by including various facts in the press release that testified to the status of these flowers in the history of culture. Reading the text, one might well suppose that the exhibition was the whim of an influential and museum-affiliated artist who was given the opportunity to present his hobby to the general public. Critics at the time and historians later paid little attention to the exhibition.

Today, however, in the history of art Delphiniums are regarded as the originator of the bio-art movement. The author of the bio-art anthology Signs of Life writes that Steichen “was the first modern artist to create new organisms through both traditional and artificial methods, to exhibit the organisms themselves in a museum, and to state that genetics is an art medium.” [ 1 ] 1. Eduardo Kac, Signs of Life: Bio Art and Beyond. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007, p. 10. It is unlikely, that Steichen – a commercial salon photographer – was seriously interested in the ontology of art at a theoretical level. For him flower selection was an occupation which, like photography, had to do with an aesthetic experience, an appeal to beauty.

The assessment by art historians of Steichen’s work as a dotted line linking Cubism with George Gessert’s later bio-art practices seems stretched and teleological. It is much more interesting to look at what such a project, implemented without design and little reflected in its time, can tell us about today’s understanding of art and its growing interest in the natural world. In this sense, we cannot treat the flowers simply as a “personal appearance”, as a modification of the readymade brought into the gallery-museum context. We need to pay attention to the actual process of their formation and materialization, of which Steichen himself said: “The science of heredity when applied to plant breeding, which has as its ultimate purpose the aesthetic appeal of beauty, is a creative art.” [ 2 ] 2. Edward Steichen, ‘‘Delphinium, Delphinium and more Delphinium!,’’ in The Garden (March 1949), cited in Kac, op. cit., p. 11. Cleary this “creative art” is at the same time a “creative act” and what interests me is not so much a new medium, genre, species, technique or movement in art, but the fundamentally different approach, which Steichen proposes, to the creative act. It, as we will see, concerns three basic levels: art production (artistic method), the way of being of art (ontological status of the work) and its consumption (reception).

First of all, the application of hybridization to art production forces us to reconsider the concept of authorship. Poststructuralism demythologized the romantic figure of the author by asserting the unoriginal and self-citing nature of any work (the author, according to Roland Barters, is always just a “tissue of quotations”). [ 3 ] 3. Roland Barthes, “The Death of the Author” in Image Music, Text. London: Fontana, 1977, p. 146. The new materialism, in the optics of which it is logical to describe Steichen, understands the artistic process as “co-collaboration”, that is, the joint action of artist and material. Modernist art was based on the principle of hylomorphism, i.e. the idea that passive material is shaped by an active form, that form being the discourse itself (art criticism, philosophy, history of art), which, through the artist as an abstract function, determines the distribution of the material (paint on canvas, metal in space, etc.).

Steichen offers another model, where the form is not just superimposed on material, forming their synthesis in a complete object, but, in the words of neo-materialists, “matter is as much responsible for the emergence of art as man.” [ 4 ] 4. Estelle Barrett, Barbara Bolt (Eds.), Carnal Knowledge: Towards a 'New Materialism' through the Arts. London, New York: I. B. Tauris, 2012, p. 6. In other words, the substrate, the substance of art, is not simply used to achieve some or other artistic or conceptual goals. Matter is endowed with its own agency, its own will or goal-setting capacity. For example, for contemporary artists, the molecular forces of paint become important – the stratification of substances in themselves and as they are. So the artist is reduced to the role of partner or assistant of self-developing, pulsating matter, which has its own “interests” and “intentions” and is thus not reduced to an effect of discourse. [ 5 ] 5. Here we may well recall the process art of the 1960s, but it emphasized the physical processes of entropy (soulless substance) rather than the (quasi-)biological processes of evolution. Such matter is emergent, self-organizing and generative. Steichen’s example is especially interesting, because the plant breeder works, not with inorganic, but with organic substance, penetrating into its very essence. [ 6 ] 6. Speaking of genetic design, one might argue that DNA manipulation, far from reducing the artist to an assistant, makes him into a demiurge, and many current fears regarding genetic technologies are based on this assumption. The artist takes what is "natural", and subjects it to an "artificial" combination. The creative work of human hands, as it were, cancels out the logic of evolution. But the artist does not create life, but only adjusts the steering wheel of evolution and holds fast for a while the mutations that evolution has produced. A work of art has no beginning or end, it is open and evolving in the mostt direct sense. Until scientists have learned how to synthesize life abiogenetically, the artist is not a creator, but remains only a helmsman. The artist is the helmsman of evolution.

Following these crude historical parallels with the modernists leads to the following conclusions about the avant-garde. The artist of the historical avant-garde tried to combine art and life, where life is understood as social reality (bios), because his or her work was intended to create a new utopian world. Steichen, however, tries to break down the boundaries between art and zoé – life itself. Posthumanists understand zoé as the dynamic, self-organizing structure of life itself – generative vitality. [ 7 ] 7. Rosi Braidotti, The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity, 2013, p. 60. It is interesting that Rosie Braidotti, who recognizes the intrinsic value of life (zoé) as such, calls this approach a “colossal hybridization of the species”, [ 8 ] 8. Ibid., p. 65. where there is no significant difference between man and his natural “others”. The artist does not stand opposed to the flower. They are both part of the same creative act. Not only does Steichen hybridize delphiniums, but delphiniums hybridize him, their breeder.

Steichen’s interest in the bare factuality of the material lends him an affinity with contemporary artists. Steichen was not only fascinated by the technical and representative possibilities of photography; he was also interested in the chemical process of image production itself. Just as he produced huge numbers of negatives, most of which were never converted to positives, so he grew thousands of delphiniums in order to select the best examples. The production process here was like a struggle for survival, natural selection (or curatorial selective practice), and not a concentrated honing of the original. The artist was driven by a passion for selection – the practical side of theoretical genetics, which was at the peak of its development at that time. Selection had been a human capacity for millennia, but it was first carried out by scientific methods (and not blindly) in Steichen’s time. At that time (before Lysenkoism or before the complete discrediting of eugenics by fascism) it was perceived as a science of the future, comparable with the utopian pathos of the avant-garde, which swallowed not only bios, but also zoé.

Selection is based on the process of hybridization, whereby genotypes are chosen for their nutritious or aesthetic qualities, the preferred individuals are crossed with one another and those of their descendants which inherit all of the required features are in turn selected. So, generation by generation, the breeder brings the plant to the required state as expressed in its phenotype (i.e., the externally manifest features of the individual). Selection, therefore, in contrast with species isolation, is a matter of breaking down the boundaries of species – that “great bastion of stability,” as the biologist Ernst Mayr called it. Mayr gave a biological definition of species as “groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations which are reproductively isolated from other such groups.” [ 9 ] 9. Ernst Mayr, Animal Species and Evolution. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1963, p. 19. Today, in the light of new discoveries or the spread of hybrids and chimeras in biotechnological experiments, biologists and philosophers increasingly emphasize the limitations of this definition, although Mayr deserves credit for not absolutizing the nature of species boundaries.

Perhaps such a parallel will seem factitious, but if traditional contemporary art is based on the production of a certain type of art (the medium) or a specific individual (the work), in Steichen’s case, we find it hard to draw the boundary. Are his works only those delphiniums that were shown at MoMA in 1936? Or their seeds, which can still be bought today? Rather, hybridization can be understood as a process that emphasizes the conventionality of species differences. So he does not address a species, population or individual organism, but liberates life itself, the constant fluidity of the vital forces of nature (and of art). Artistic hybridization is a queer practice par excellence, a practice which highlights the very process of becoming rather than fixed identities. Such art and life is a constant movement of creating and erasing boundaries through the temporary accentuation of genetic mutations.

Hybridization not only changes the role of the artist (into an assistant to the material) and the status of art (into a constant becoming), but also makes the process of perception mutually directional. The philosopher Catherine Malabou believes that the paradigm of writing, which prevailed in the days of poststructuralism, is being replaced by the paradigm of plasticity – the ability to both acquire and give form. [ 10 ] 10. Catherine Malabou, Plasticity at the Dusk of Writing. Dialectic, Destruction, Deconstruction. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009. Plasticity plays an important role in biology, particularly in the framework of a new evolutionary synthesis (sometimes misleadingly called “postmodernist”), where species are not considered in isolation from ecosystems. Suffice it to recall Charles Darwin, who poetically described the co-evolution of insects and flowers, where not only does the insect adapt to the shape of the flower, but the structure of the flower also uses ruses and devices in response to the requests and desires of the insect. Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari would later describe this process as that of de- and reterritorialization: “The orchid deterritorializes by forming an image, a tracing of a wasp; but the wasp reterritorializes on that image. The wasp is nevertheless deterritorialized, becoming a piece in the orchid’s reproductive apparatus. But it reterritorializes the orchid by transporting its pollen.” [ 11 ] 11. Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaux. Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

The relationship of flowers and insects is a ménage-à-trois (for example, pistil, stamen and bee), but together with the artist they form a love rectangle or trapezoid, where all of the participants are equally involved in the process of receiving and passing on a form. And to understand this process, we must turn to an area that is (quite understandably) neglected by art theorists, namely, evolutionary or Darwinian aesthetics. This teaching is based not on the widely known idea of the survival of the fittest, but on the idea of sexual selection, i.e. differentiated access to partners (competition and choice of a partner of the opposite sex). The theory was developed by Darwin himself, who, trying to explain apparently redundant ornamentation on the bodies of animals, believed that sensual pleasure, attractiveness and subjective experience are also agents of selection.

This question remains a matter of controversy in evolutionary biology, where representatives of the two camps continue to disagree. The “adaptationist” interpretation insists that bodily ornamentation advertises and provides information about the useful qualities of the partner, while an alternative “arbitrary” model sees no benefit in the production of aesthetic attributes other than the popularity of the partner. The latter approach was developed by Darwin’s follower, Ronald Fisher, who described sexual selection as a positive feedback mechanism. For example, the more advantageous it is for a male to have a long tail, the more advantageous it is for a female to prefer just such males, and vice versa (in biology this principle is called “Fisherian runaway”). His radical follower, our contemporary Richard Prum, has pursued this line of thought, which also correlates with plasticity: partner preferences are genetically correlated with preferred features. In other words, “variation in desire and variation in the objects of desire will become correlated or enmeshed, entrained evolutionarily,” [ 12 ] 12. Richard Prum, “Duck Sex and Aesthetic Evolution” in Life: The Leading Edge of Evolutionary Biology, Genetics, Anthropology, and Environmental Science (John Brockman, Ed.). New York, NY: Harper, 2016, p. 333. beauty and the observer co-evolve. Aesthetic attractiveness makes the body free in its sexuality: “birds are beautiful,” Prum writes, “because they are beautiful to themselves.” [ 13 ] 13. Ibid., p. 348.

Feminist critiques of Darwinism, however, go much further in defending Darwin against reductionism. For example, Elizabeth Grosz questions the raison d’être of sexual selection and emphasizes its irrational character, expressed in an unbridled intensification of colours and shapes, extravagance, excessive sensuality and an appeal to sexuality rather than simple reproduction. She tries in this way to separate natural from sexual selection (the second is usually considered a subspecies of the first). In particular, she writes: “Sexual selection may be understood as the queering of natural selection, that is, the rendering of any biological norms, ideals of fitness, strange, incalculable, excessive.” [ 14 ] 14. Elizabeth Grosz, Becoming Undone: Darwinian Reflections on Life, Politics, and Art. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011, p. 132. Moreover, sexual selection expands the world of the living into ”the nonfunctional, the redundant, the artistic.” [ 15 ] 15. Ibid. And here we are again reminded of Steichen’s Delphiniums, which only intensify the already excessive beauty of this flower. But how does this leap from nature to culture happen? Why does a person become an addressee of someone else’s sexual selection? How does he or she get drawn into this “co-evolutionary dance”?

Describing the attractiveness of flowers (including delphiniums) and their ability to come to life in our imagination, Elaine Skerry highlighted their various characteristics: the size that allows them to freely penetrate our consciousness, the bowls that correspond to the curve of our eyes, the possibility of their localization by vision, the transparency of their substance, etc. [ 16 ] 16. Elaine Scarry, “Imagining Flowers: Perceptual Mimesis (Particularly Delphinium)” in Representations, Vol. 57 (Winter 1997), pp. 90–115. However, this says little about plasticity. Without extrapolating biological principles to social ones, I would propose that an even more complex process is at work in Steichen’s love rectangle or trapezoid, where not only does the artist subordinate the flower to his aesthetic needs, but the flowers themselves determine the artist’s sensory experience. The reception and consumption of art cannot be a one-way process, but are subject to positive or negative feedback. There is no need to go far for an example: in Russia flowers of Northern European selection (the so-called “the new perennials”) – calmer, more austere and vegetative – are gradually supplanting the gaudy and bright flower varieties that were popular in Soviet times. We can easily trace how flowers steer our taste. Could it be that our taste, our aesthetic judgment, is also a hybrid?

Following in the steps of Steichen’s experiments, I have tried to retroactively comprehend what hybridization as a creative act might be today. However, despite all that has been said above, I am not sure that hybridity in itself is of indubitable value. We know from evolutionary theory that mixing does not always lead to diversity, and the endemics so dear to us are a product of the isolation of species (“Splendid Isolation” is the title of a book about the remarkable mammals of South America), [ 17 ] 17. George Gaylord Simpson, Splendid Isolation: The Curious History of South American Mammals. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1980. because “isolating mechanisms” between species preserve originality and authenticity. In a similar vein, some left-wing philosophers say that by altogether abandoning identity politics and insisting on the fluidity of categories, we make ourselves vulnerable to traditionalism. For instance, if you consider yourself fluid, what prevents you from abandoning your essence and accepting a fixed norm? Hybridity also comes in for criticism as a product that masks the policy of global imperialism, because it is based on the exclusion of “others”: old age, uncommunicativeness, pain, i.e., non-hybridity itself. [ 18 ] 18. Haim Hazan, Against Hybridity: Social Impasses in a Globalizing World. Cambridge: Polity, 2015.

Hybridity and its dark double, non-hybridity, are in equal measure social constructs. Perhaps everything around us is equally hybrid. However, the hybridization procedure is not just a progressive trope, but also a subversive procedure. Hybridization, unlike many other analogous concepts, is associated with biology, i.e., with something natural and inherent to nature itself, but at the same time is also a cultural practice of selection, and for this reason it undermines naturalness as such. Unlike concepts that naturalize, that represent human history as something natural, it naturalizes unnaturalness itself. The unnatural seems natural. As Steichen shows us, the boundaries between art and nature are highly arbitrary. Life imitates art. Art imitates life.

Translation: Ben Hooson

- Eduardo Kac, Signs of Life: Bio Art and Beyond. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007, p. 10.

- Edward Steichen, ‘‘Delphinium, Delphinium and more Delphinium!,’’ in The Garden (March 1949), cited in Kac, op. cit., p. 11.

- Roland Barthes, “The Death of the Author” in Image Music, Text. London: Fontana, 1977, p. 146.

- Estelle Barrett, Barbara Bolt (Eds.), Carnal Knowledge: Towards a 'New Materialism' through the Arts. London, New York: I. B. Tauris, 2012, p. 6.

- Here we may well recall the process art of the 1960s, but it emphasized the physical processes of entropy (soulless substance) rather than the (quasi-)biological processes of evolution.

- Speaking of genetic design, one might argue that DNA manipulation, far from reducing the artist to an assistant, makes him into a demiurge, and many current fears regarding genetic technologies are based on this assumption. The artist takes what is "natural", and subjects it to an "artificial" combination. The creative work of human hands, as it were, cancels out the logic of evolution. But the artist does not create life, but only adjusts the steering wheel of evolution and holds fast for a while the mutations that evolution has produced. A work of art has no beginning or end, it is open and evolving in the mostt direct sense. Until scientists have learned how to synthesize life abiogenetically, the artist is not a creator, but remains only a helmsman.

- Rosi Braidotti, The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity, 2013, p. 60.

- Ibid., p. 65.

- Ernst Mayr, Animal Species and Evolution. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1963, p. 19.

- Catherine Malabou, Plasticity at the Dusk of Writing. Dialectic, Destruction, Deconstruction. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

- Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaux. Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

- Richard Prum, “Duck Sex and Aesthetic Evolution” in Life: The Leading Edge of Evolutionary Biology, Genetics, Anthropology, and Environmental Science (John Brockman, Ed.). New York, NY: Harper, 2016, p. 333.

- Ibid., p. 348.

- Elizabeth Grosz, Becoming Undone: Darwinian Reflections on Life, Politics, and Art. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011, p. 132.

- Ibid.

- Elaine Scarry, “Imagining Flowers: Perceptual Mimesis (Particularly Delphinium)” in Representations, Vol. 57 (Winter 1997), pp. 90–115.

- George Gaylord Simpson, Splendid Isolation: The Curious History of South American Mammals. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1980.

- Haim Hazan, Against Hybridity: Social Impasses in a Globalizing World. Cambridge: Polity, 2015.