moma: cubism and abstract art, 1936

The section of retrospective reviews on MoMA exhibitions continues with Nikolai Punin’s text on Cubism and Abstract Art (1936).

Once upon a time, in the greatest city of the New World there lived an adventurous young man. Being an explorer and ethnographer at heart, he longed to travel and make great discoveries. Then it happened one day that he heard a story about some curious developments among the natives of the Old World. A new kind of making and decorating of art objects, it was said, had been spreading among the craftsmen of various tribes. The movement was already dying, however, and soon it would slip into oblivion.

Intrigued, the explorer immediately organized a series of expeditions across the ocean. He visited all the important places, collected paintings and other exotic objects from the natives and recorded the stories they told. Impressed with what he saw and heard, he brought back many artifacts and decided to establish an ethnographic museum, naming it the Museum of Modern Art.

Soon afterward, the explorer organized an exhibition of the two most unusual styles, which were known as “Cubism” and “Abstract Art”. The exhibition was a great success, and it became the standard for the museum’s permanent display. It was also widely imitated by the museums of modern art that came after.

From “Tales of the Artisans”

This old tale about the beginnings of the Museum of Modern Art tells us much about its landmark 1936 exhibition, Cubism and Abstract Art, curated by the Museum director, the “young ethnographer,” Alfred Barr. The Museum’s press release announced the exhibition, Cubism and Abstract Art, to last from March 3 until April 19, which “traces the development of cubism and abstract art and indicates their influence upon the practical arts of today”. The release goes on to explain that “the Exhibition is representative largely of European artists for the reason that only last season the Whitney Museum of American Art held a comprehensive exhibition of abstract art by American artists”. [ 1 ] 1. MoMA press-release №22036-6. This seems to be a formal excuse for not extending the exhibition to include American artists, who, in the opinion of MoMA at the time, were inferior to the Europeans. A few years later, in 1940, answering criticism for not including American art in its main narrative, the Museum wrote in its regular bulletin that “the Museum of Modern Art has always been deeply concerned with American art”, but added that the mission of the institution was to show works “that were of superior quality as works of art”. [ 2 ] 2. “American Art and the Museum” in: The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art Vol. 8, No. 1, American Art and the Museum (Nov., 1940), pp. 3–26.

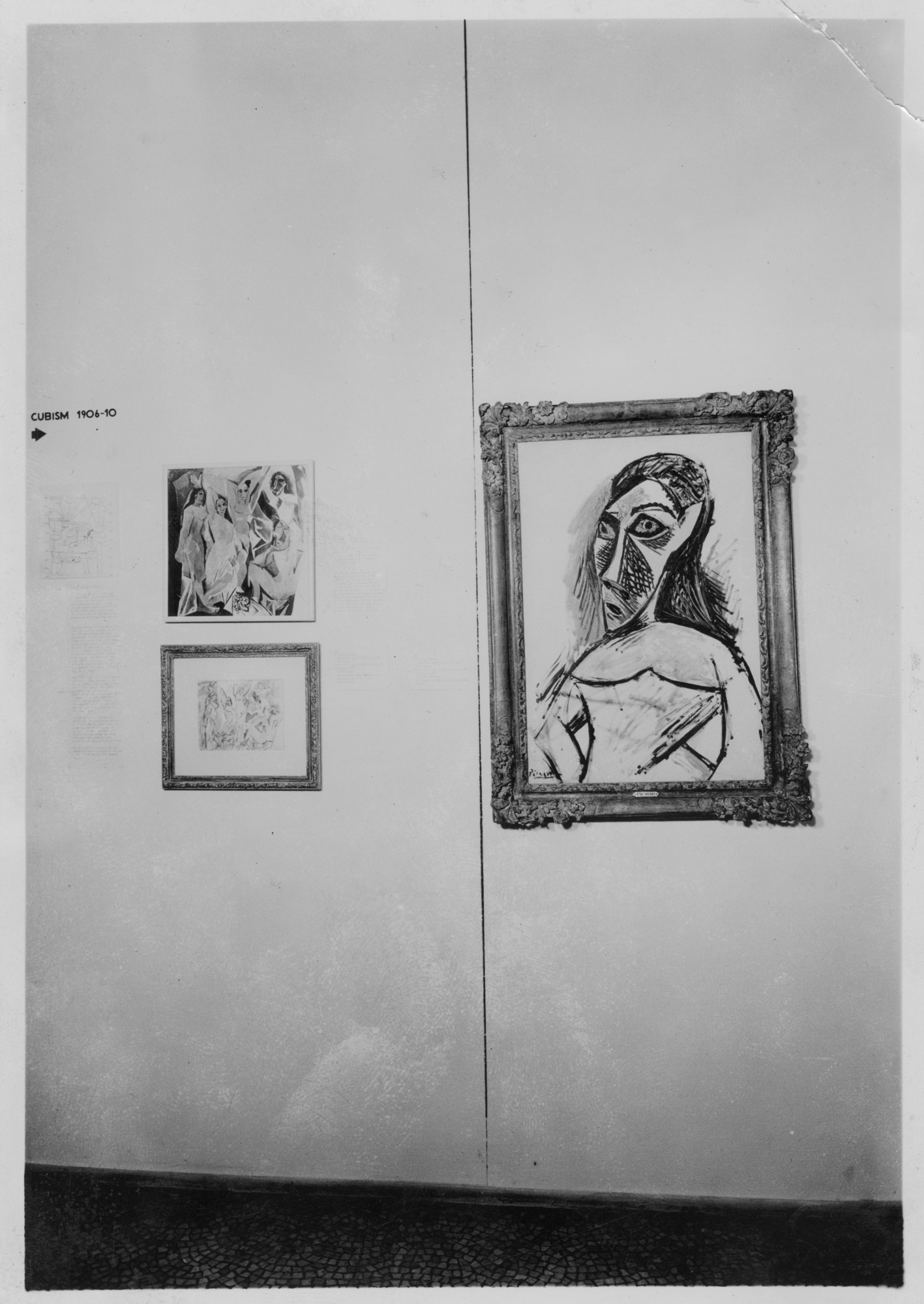

Photographs of the 1936 exhibition show a conventional installation. The works were hung in a mainly linear succession, obeying the museum standard of the time. However, some details deserve notice. The principal theme of the exhibition, the Cubist movement, begins with Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (demurely translated for the American audience as “The young ladies of Avignon”). What we see, though, is not the original painting, but a small photo reproduction. The exhibition catalogue begins its chronology with Les Demoiselles, and mentions, opposite the plate of the picture, that the original is “not in exhibition”. The banal explanation is that the original could not be acquired for the exhibition, but it is surely interesting that the exhibition, which defined the story of modern art, began with a reproduction. Les Demoiselles was not the only reproduction on show. A plaster copy of the 4th century Greek Nike of Samothrace can be seen in views of the Futurist section. Inclusion of the Greek work, on a high pedestal above the Unique Forms of Continuity in Space by Umberto Boccioni, is meant to suggest parallels between these sculptures, separated by more than two thousand years and yet contemporary (since the Nike was a recent copy). Several constructions by Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko were also represented by photo-reproductions, since there was no possibility of bringing the originals to New York. Two chairs by Marcel Breuer and Le Corbusier, hanging on the walls of the Bauhaus section, are another interesting installation detail. They had previously been included in Herbert Bayer’s Deutscher Werkbund installation in Paris in 1930.

Two African sculptures are visible in views of the Cubist section, one between works by Picasso and another between the Bather by Jacques Lipchitz and the painting Brooklyn Bridge by Albert Gleizes. Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase hangs on a wall next to the staircase, while various works hang on doors instead of walls. Most of the installation views of paintings and sculptures are unremarkable, but the way in which exhibition displayed posters, photography, designed objects and architecture together with “high art” was unusual for the time. An outstanding feature of the exhibition was its inclusion of fourteen works by Kazimir Malevich, relatively unknown in the USA at the time. The works were grouped together in one room and all of them were brought to New York by Alfred Barr, who had acquired them from Alexander Dorner, the director of the Landesmuseum in Hannover, in 1935. In the mid-1930s modern art was being removed from museums in Germany and had already disappeared from Soviet museums, so, for many years to come, the Museum of Modern Art in New York would be the only place where works by Malevich could be seen. I am not surprised by the importance lent to Malevich by Alfred Barr since I remember how impressed the young American was when I led him through the Russian Museum to see the art of Malevich and other related works.

Another artist whose work was given prominence in the exhibition is Piet Mondrian. Mondrian spent most of his life in Paris where he produced all of the neoplastic paintings, for which he became famous, but his paintings would not become museum exhibits in Paris until 30 year after his death. It was the 1936 exhibition at MoMA that gave Mondrian his place in the modern narrative. If we honor Malevich and Mondrian today, that is in no small part due to the 1936 exhibition at MoMA.

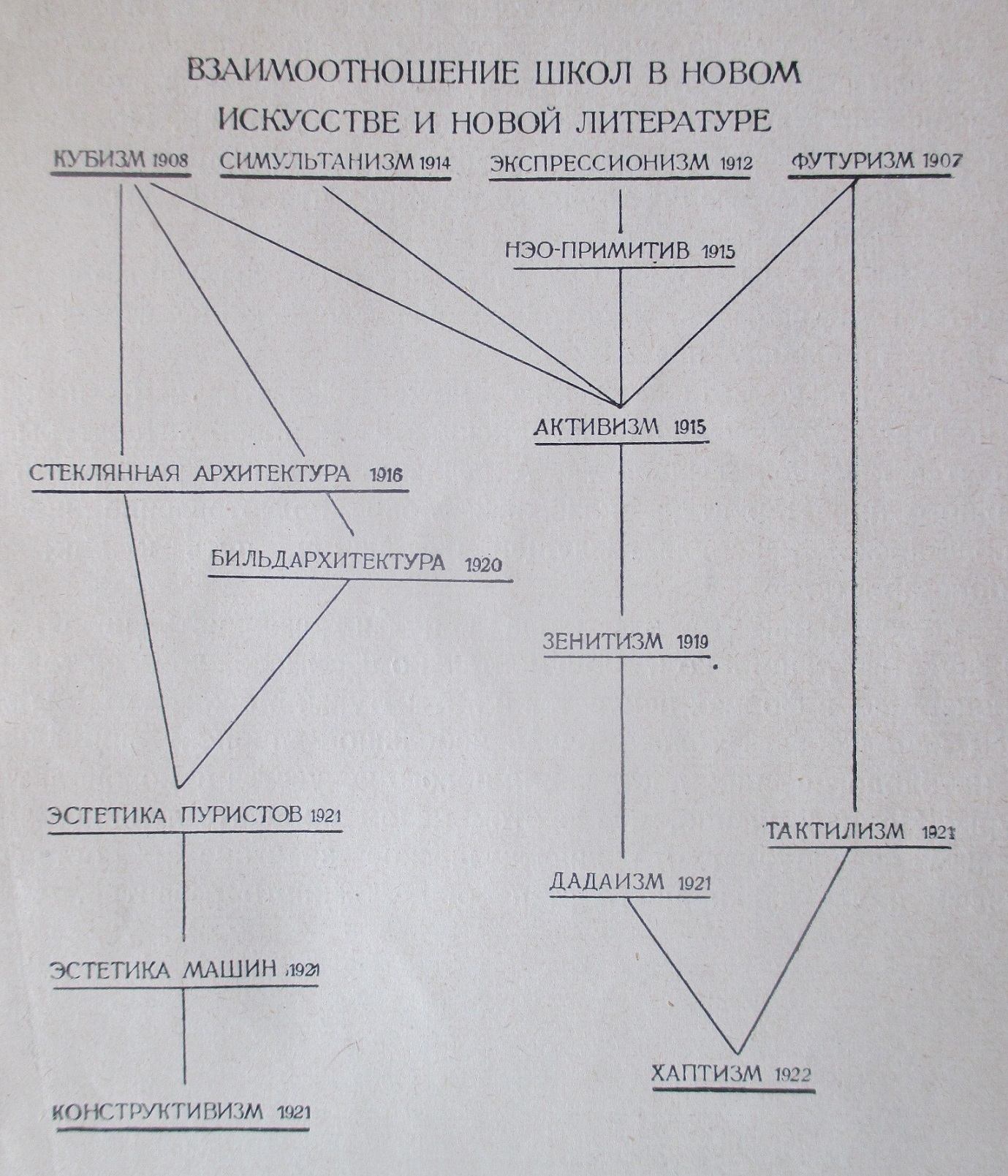

But what gives the exhibition its exceptional importance is not its installation, but the story that it tells – the story we see summarized on the cover of the exhibition catalogue as Alfred Barr’s now famous “genealogical tree”, representing in graphic form the historicization of the previous four decades of European modern art. It is quite possible that Barr saw a similar diagram by Ivan Matsa, entitled Relationships Between the Schools in New Art and New Literature (1926) when he visited Moscow in 1928.

According to Barr’s diagram, the story of modern art began with Post-Impressionism (Cézanne) and branched in two directions, one towards Fauvism (Matisse), Expressionism, and Non-Geometrical Abstract Art, and the other towards Cubism (Picasso), Suprematism, Constructivism, Neo-Plasticism, and Geometrical Abstract Art. Organized chronologically and by “international movements”, Barr’s genealogical tree was a radical departure from the concept of “national schools”, which dominated European art historiography and which was embodied in art museums and in the most prestigious art event of the time, the Venice Biennale. The first page of the catalogue explained that, in addition to painting and sculpture, the exhibition included such categories as construction, photography, architecture, industrial art, theatre, film, poster art, and typography, thus introducing an expanded notion of “art” into the museum context.

The Russian/Soviet avant-garde, one of the most important cultural developments of the 20th century, was extensively represented in the catalogue. It was historicized as an integral part of this new “international narrative” of modern art, at a time when its achievements had been removed from public view, both in the Soviet Union and Europe. The vital role of Barr’s exhibition in bringing the art of Malevich to international recognition was already mentioned, but the same holds true for the works of Tatlin, Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova and Lyubov Popova. It is thanks to Barr’s exhibition that their works are so internationally well-known and respected today. The very first (and second) name mentioned in the introduction is that of Malevich, and the introduction ends with reproductions of works by Malevich and Wassily Kandinsky as examples of “geometrical” and “non-geometrical abstract art”. The catalogue reproduced an installation view of the Abstract Cabinet by El Lissitzky which, at that very time, was being dismantled for inclusion in the Nazi Degenerate Art exhibition held in Munich in 1937.

Barr’s exhibition coincided with the disappearance of modern art throughout Europe. The internationalism of the avant-garde was anathema to the nationalist tide that swept through Europe in the 1930s, precipitating war and carnage. Modern art was completely marginalized and removed from museums as “bourgeois and formalistic” in the Soviet Union, and was labeled “degenerate, Jewish, and Bolshevik” in Germany. In France, the land from which it sprang, modern art was, ironically enough, never brought into museums in the first place. In the US, most of the public and the political establishment had no love for modern art, but since art was not a government matter, MoMA, as a private corporation, could exhibit and promote its program freely, without state interference. As my friend Walter Benjamin once noted, this is why the American public could see European modern art at a time when there was no modern art in Europe, and MoMA became a kind of Noah’s Arc of European modern art.

Walking through MoMA’s halls in 1936, most American museum-goers probably had no idea that what they were seeing was not Europe’s present, but its past. Nor can they have been aware that, although all of the artworks were from Europe, the story told through the arrangement of the museum’s exhibits was not European – it was not a European interpretation of modern art. Although often criticized as “formalistic”, the story told in the exhibition and in Barr’s catalogue did not merely preserve the memory of European modern art, but reinvented it by categorizing artists according to “international movements” instead of “national schools”. This historicization of European art was almost entirely based on artifacts brought from overseas and then assembled and interpreted by someone from another culture. From today’s perspective, MoMA’s role was not only that of an art museum, but of an ethnographic museum. In the avant-garde-centered MoMA narrative, modern art was almost entirely a European phenomenon with Paris as its capital and Picasso as its most prominent artist. After the catastrophe of the World War II, MoMA was perceived in Europe as the most important museum of modern art in the world. By admiring this American museum, “natives” of the Old World were unaware that they implicitly adopted its story – a story about their own art and culture. Gradually, this story became the canonical narrative on both sides of the Atlantic, determining future developments in Western art for decades to come.

***

Today the art scene worldwide is based on internationalism, individualism and (post‑)modernism as its main concepts. However, when concepts become dominant and widely accepted, the suspicion must be that they have exhausted their potential and that the future paradigm will be based on other, very different, ones.

Nikolay Punin

Berlin, 2019

- MoMA press-release №22036-6.

- “American Art and the Museum” in: The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art Vol. 8, No. 1, American Art and the Museum (Nov., 1940), pp. 3–26.