vladimir lenin and the soviet commemorative industry

Maria Silina examines monuments to Lenin as the products of a grandiose Soviet campaign that sought to promulgate specific visual symbols. Viewed through that conceptual lens a monument turns into commodified memory not just of a particular person, but of an entire commemorative industry.

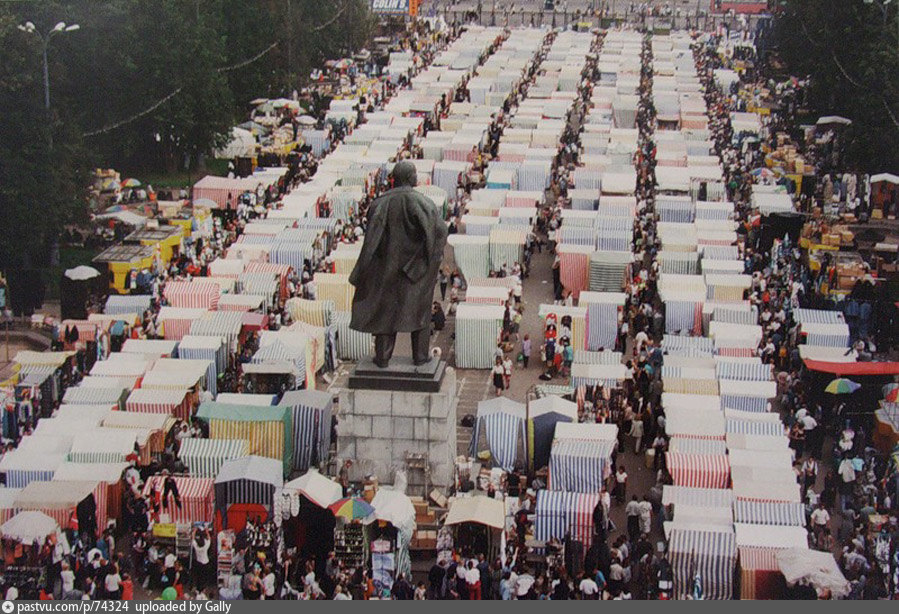

Contemporary Russians continue to live under the visual supremacy of the USSR: communist symbols, monuments, and toponyms are still pervasive elements of the post-Soviet public space. In today’s Moscow one can still find over a hundred of monuments to Lenin and hundreds of memorial plaques, commemorating, quite literally, every step made by the revolutionary leaders of 1917. Needless to say, these objects are not (critically) reframed by the current municipal authorities.

The commemoration of Vladimir Lenin in Soviet art was an archetypal modernist campaign that can serve as an excellent illustration of the commodification of public art and memory. Theoretical reflections on this subject did not begin in Western academia up until the 1960s [ 1 ] 1. Memory as commodity was analyzed by Andreas Huyssen in his Twilight Memories: Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia. London, 1995. . While the cult of Lenin itself has been thoroughly examined, almost nothing has been written about the production of the statues of Lenin and their distribution across the Eastern Bloc [ 2 ] 2. Tumarkin, Nina. Lenin Lives!: The Lenin Cult in Soviet Russia. Cambridge, 1983; Ennker, Bruno. Die Anfänge des Leninkults in der Sowjetunion. Köln, Wien, 1997. . The institutional history of the most powerful commemorative gesture in Europe — the dissemination of visual Communist symbols — is still awaiting its researchers and chroniclers [ 3 ] 3. With a notable exception: a case study of Latvian art production by Sergei Kruk. "Profit rather than politics: the production of Lenin monuments in Soviet Latvia." Social Semiotics. 20:3. (2010): 247−276. .

In what follows I will consider the ways of producing, distributing, and promoting monuments to Lenin in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and will reflect on their function and legacy in contemporary public space. I will examine 1) the techniques and methods employed in the production of the statues of Lenin 2) the creation of a network of rituals and traditions, centered around these monuments. Finally, I shall contemplate the outcomes of the commemorative campaign geared towards the immortalization of Lenin in post-Soviet Russia.

It is noteworthy that the groundwork for the dissemination of the cult of Lenin was laid even before his death in January 1924. The first museum collection of Lenin’s works and personal items, such as paintings, photos, private letters, etc. was supposed to be exhibited in May 1923. By then Lenin had already been terminally ill [ 4 ] 4. More on the Lenin Institute in Mosolov, V.G. IMEL: Zitadel Partiinoy Ortodoksii. Iz istorii Instituta Marskizma-Leninizma pri ZK KPSS, 1921−1956. Moscow, 2010: 107−184. On initial projects of Lenin Museum: "Muzei Vladimira Ilicha." Pravda. 23 Aug. 1923: 3. . When he died the following year, there was no hesitation or uncertainty as to how his memory should be preserved. The Commission of the CEC (Central Election Commission) of the USSR for the Immortalization of the Memory of V. I Ulyanov-Lenin was established with an explicit purpose of organizing Lenin’s funeral and overseeing proper memorial ceremonies [ 5 ] 5. Shefov, A. N. Leniniana v sovetskom izobrazitel’nom iskusstve. Moscow: 1986: 82−89. .

Lenin died on January 21, 1924. Two days later, local authorities in Petrograd decided to rename the city into Leningrad (literally the city of Lenin) and to erect a monument to the deceased Bolshevik leader. Five days later, it was decided to build a crypt and a number of monuments in the largest Soviet cities. Six days later, municipal authorities in Moscow launched a fundraising campaign to erect the “greatest monument to our leader.” In conjunction with these proposals other commemorative and propagandistic initiatives gained momentum, such as the resolution to publish the complete works of Lenin, to set up Lenin Corners (a social center of sorts equipped with benches and chairs and shelves lined with books, journals and magazines, where workers or soldiers could read, play checkers, listen to the radio and consult the helpful staff that was always eager to clarify the readings or answer questions — translator’s note), to establish a Lenin Foundation and so much more. In May 1924, only four months after Lenin’s death, the first museum dedicated to him was unveiled [ 7 ] 7. On the early history of building Lenin museums see: Rozanov E. G., Reviakin V. I. Arhitektura muzeev V. I. Lenina. Moscow, 1986: 7−25. .

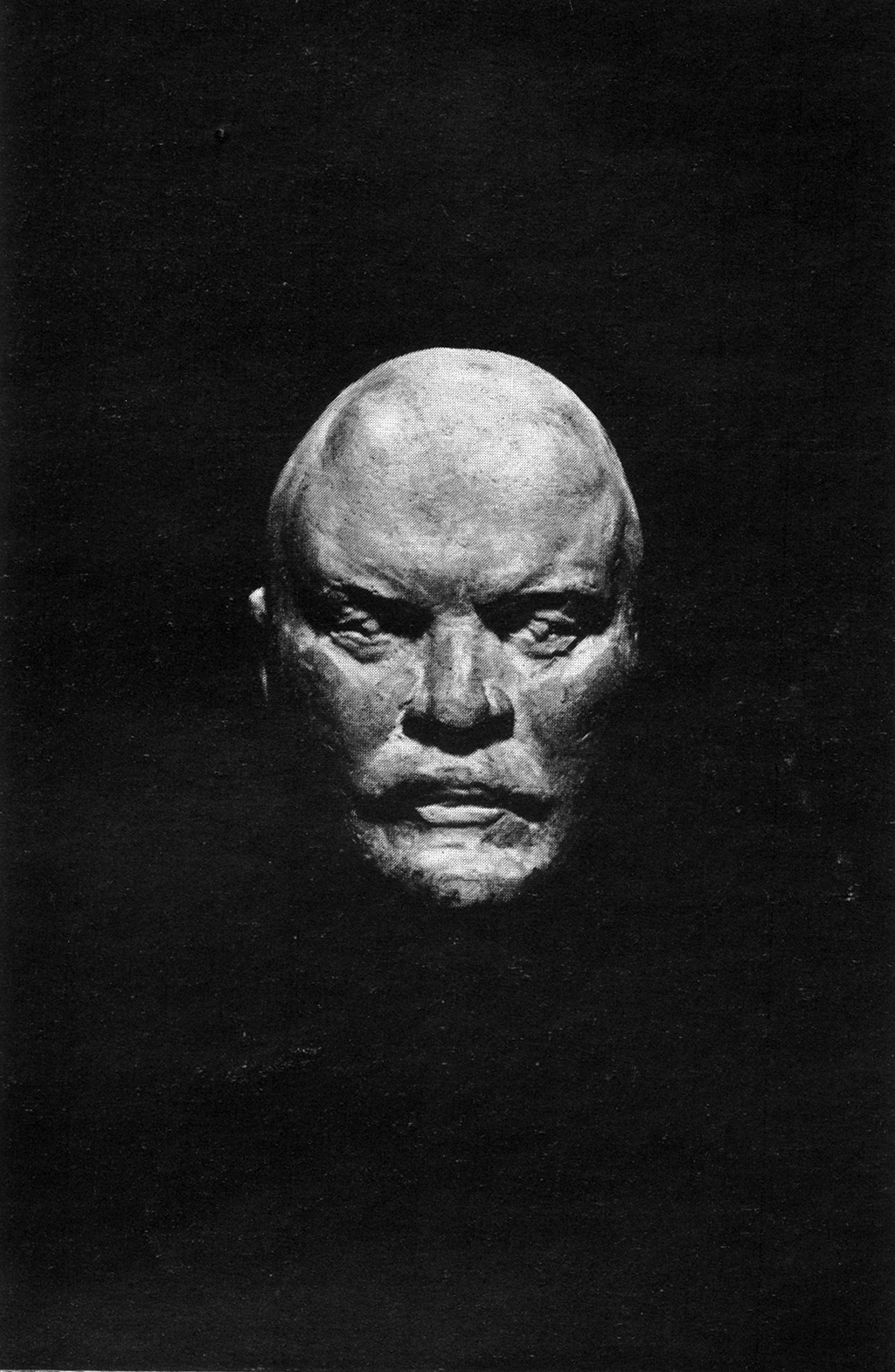

Shortly afterwards Leonid Krasin, one of Lenin’s closest associates and comrades, a Soviet diplomat and the head of the Commission for the Immortalization of the Memory of V. I. Ulyanov-Lenin, published an article “On architectural commemoration of Lenin” in a volume titled “On Lenin’s Monument.” Krasin proposed to erect a mausoleum by deciding on the design of the future crypt and argued that a realistic image of Lenin’s facial traits (i. e. his portrait without any stylization of his appearance) should be preserved as well, since according to Krasin, this would convey the personal charms of the deceased Party leader [ 8 ] 8. O pamiatnike Leninu. Leningrad, 1924: 21−33, Khudozhestvennaia zhizhn', 173−176. .

Soon enough depictions of Lenin did assume truly scientific precision, consistency and regularity. Two basic principles at work were thought to guarantee the highest quality of any monumental portrait: 1) people who had been personally acquainted with Lenin were invited to consult the artists working on his portraits, 2) artists had to study Lenin’s photographs to ensure documentary authenticity of their own work.

However, the first monuments presented to the public showed that these early portraits of Lenin lacked the necessary artistic and, more importantly, documental quality. That is why in June 1924, half a year after Lenin’s death, the CEC issued a Resolution on the reproduction and distribution of busts, bas-reliefs, etc. carrying the image of V. I. Lenin. Besides the central Commission, which was based in Moscow, local branches were also established in Leningrad, Ukraine, and Transcauscasia. They were called upon to exercise control over the production of portraits and other images of Lenin [ 9 ] 9. Khudozhestvennaia zhizhn', 191−192. . Besides being endowed with the authority to censor productions deemed improper, each commission was obliged to have one member in its ranks who had personally known Lenin. The practice of inviting people who had been personally acquainted with him or even met him once, however fleetingly, in order to consult sculptors or painters, persisted for decades to come.

Just how such consultations were held can be surmised from an excerpt of the transcript of a discussion around the project for the monument to Lenin in his native Ulyanovsk in the later 1930s. The renowned sculptor, Matvei Manizer, who was working on his project, was advised by none other than Lenin’s widow, Nadezhda Krupskaia. When examining the maquette of the future sculpted portrait, Krupskaia noted: “[You depicted him with] an imperious face. The shape of his body is accurate, though, but the face is supposed to show much more agitation. When he stands in front of a crowd of workers his face is much more agitated as he is trying to persuade them. When he speaks with his political opponents his facial expression is totally different, though [ 10 ] 10. Meeting of Lenin’s commemorational commission in Ulianovsk. 5 March 1938. Russian State Archive for Literature and Arts, Moscow. Box 962, 3, Folder 422. P. 26. .”

Realism was key to the depiction of Lenin’s physical appearance. However, a special, rather sophisticated allegorical language was elaborated in order to depict his clothes or posture as is evinced in the words of the local Ulyanovsk official: “We had some discussion about the proposal for a statue, [and we mentioned] that it would be too windy around it. But Lenin’s entire life was such that he always stood firm against stormy winds [ 11 ] 11. Meeting of Lenin’s commemorational commission in Ulianovsk. 5 March 1938. Russian State Archive for Literature and Arts, Moscow. Box 962, 3, Folder 422. P. 22. .”

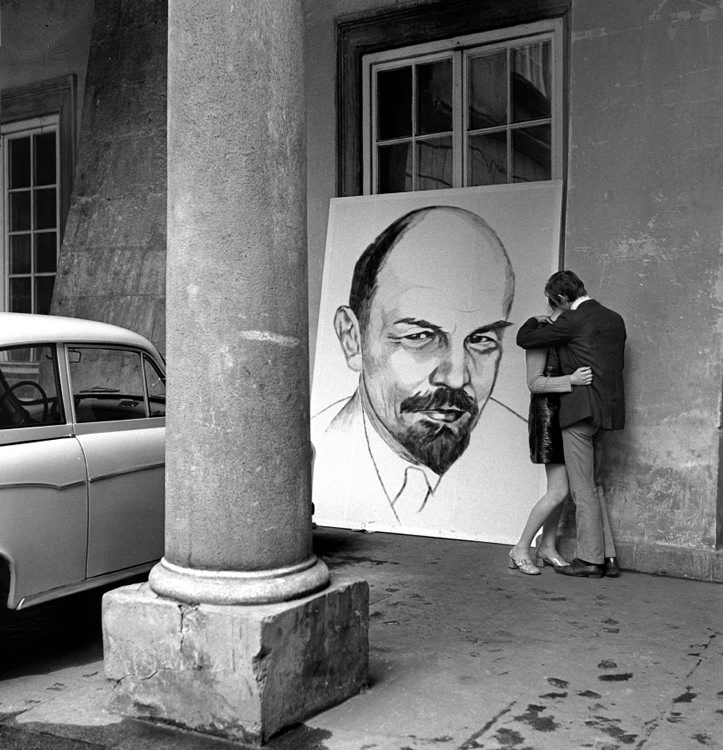

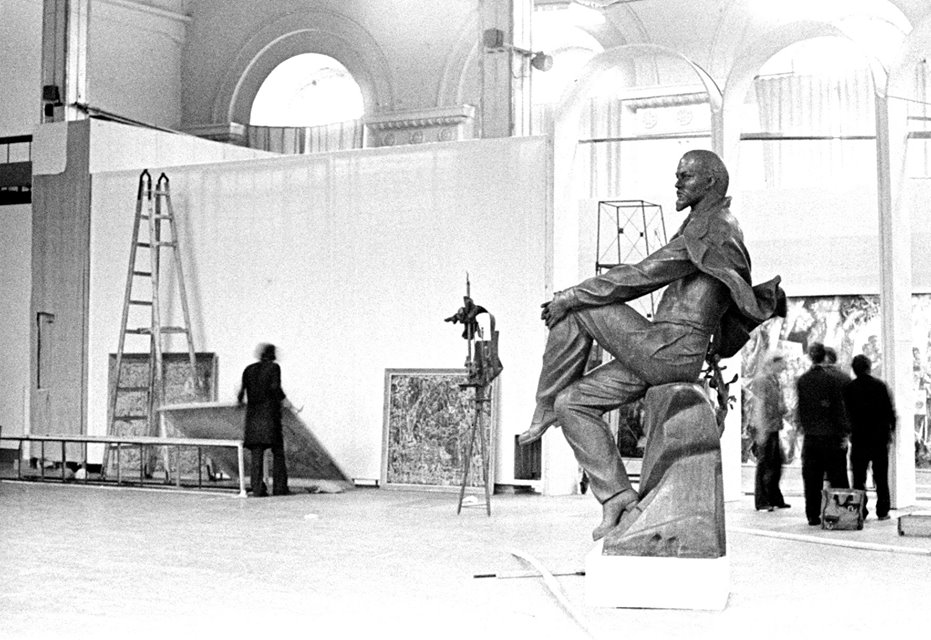

Over the next thirty years this much-debated monument was copied several times. In 1938 it was erected in Ulyanovsk; in 1960 a slightly modified version of it appeared in Moscow and finally, seven years later, to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of Lenin’s birth it was unveiled in Odessa.

Behind the statue is Sophia Loren on her visit to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union (1965, Moscow).

Some artists, such as Ivan Shadr and Sergey Merkurov, were invited to Lenin’s deathbed to draw and sculpt his body and face, to capture the last minutes of his evanescent appearance. However, it was photography that quite naturally became a far more popular source for artists portraying Lenin for many years to come. A photo album titled 1927 Lénine album. Cent photographies was published in 1927, with captions in Russian and French [ 12 ] 12. Lénine album. Cent photographies. Composé par V. Goltzeff. Moscou, 1927. . By the late 1930s, as Joseph Stalin’s cult of personality had come to dominate Soviet culture and society, the sculptural or pictorial image of Lenin underwent little if any artistic evolution and was somewhat “frozen” or “suspended”, with no new photo albums or new sources published to promote stylistic modifications or transformations. The only exception — the publication of a single album with selected art works depicting Lenin — only went to show that the range of visual sources available to artists at the time was severely limited [ 13 ] 13. Rabinovich, I. S. Lenin v izobrazitel’nom iskusstve. Moscow, Leningrad, 1939. .

Lenin’s political and visual legacy came under scrutiny and revision twice: the first time it happened in the wake of the so-called de-Stalinization of 1953−1961 and took twenty years to crystallize. The new era of commemorative practices dedicated to Lenin started in 1969−1970. It was not until 1970 that two volumes of his photos and movie-stills (a total of 343 images) Lenin. Collection of Photographs and Stills were published to honor the 100th anniversary of his birth (the book was republished again in 1980). Not only did it contain the most comprehensive collection of photos and film stills to date, capturing the slightest movement of Lenin’s body and face and the most flattering angles, but it also included an extensive and very thorough description of his appearance, almost an ekphrasis [ 14 ] 14. Lenin. Collection of photographs and stills. In 2 vols. Moscow, 1970: 7−15. .

The second wave of revisions swept across Lenin’s commemorative cult during the era of Gorbachev’s glasnost’ (1985−1991) that inspired critical reexamination of Leninism and triggered renewed interest in Lenin’s image and legacy [ 15 ] 15. Boiko, A. A. "Sotsial'no-politicheskii avtorskii plakat 1980-h godov i iskusstvo sots-arta: osobennosti, obshee i razlichiia." Neofitsial’noe iskusstvo v SSSR. 1950−1980-e gody. Moscow, 2014: 361−370. . Though stylistically the images of Lenin dated from this period evolved and changed as the artists sought to uncover the simplicity and ingenuousness of Lenin’s personality, the sources that inspired them remained the same: painters and sculptors merely altered certain minor details of clothing and posture.

In the age of photography, the Bolsheviks succeeded in employing and promoting the bourgeois art of sculpture as a proletarian art form. They also drew on the powerful ideas of the Enlightenment, such as the cult of grands hommes, as well as on the practices of the French Revolution and the cult of psychological, scientific, and factual accuracy in portraying distinguished public figures that dates back to the times of the Third Republic [ 16 ] 16. Michalski, Sergiusz. Public Monuments: Art in Political Bondage, 1870−1997. London: Reaktion, 1998. 13−55. . These ideas became deeply entrenched in the Soviet culture, all the more so due to the structure of the modernist production: the rapid creation of a very specific proletarian culture with its own traditions, lieux de mémoire, and “imaginary memories” [ 17 ] 17. Huyssen admits that he drew the notion of "imagined memory" from Arjun Appadurai’s discussion of "imagined nostalgia" in his Modernity at Large (1996). Huyssen, Andreas. Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory. Stanford, 2003. 166. . All the above mentioned initiatives staked the boundaries of a full-fledged artistic industry that encompassed commercial sculpture manufactories and enterprises that produced millions of copies of Lenin images for mass market, and an impressive range of commemorative practices and rituals, such as newspaper and magazine articles regularly appearing in the press, school trips to memorial sites and monuments, tourist guidebooks and so much more.

There were three main reasons behind the government’s eager support of the distribution of mass-produced statues to Lenin. First and foremost, the nascent country did not yet have a developed network of artists and culture-makers and the former ties connecting artists and art buyers were shattered or lost in the new economic and political reality. Cultural goods could only be distributed by and through the central authority that consolidated in its hands the entire system of production and distribution.

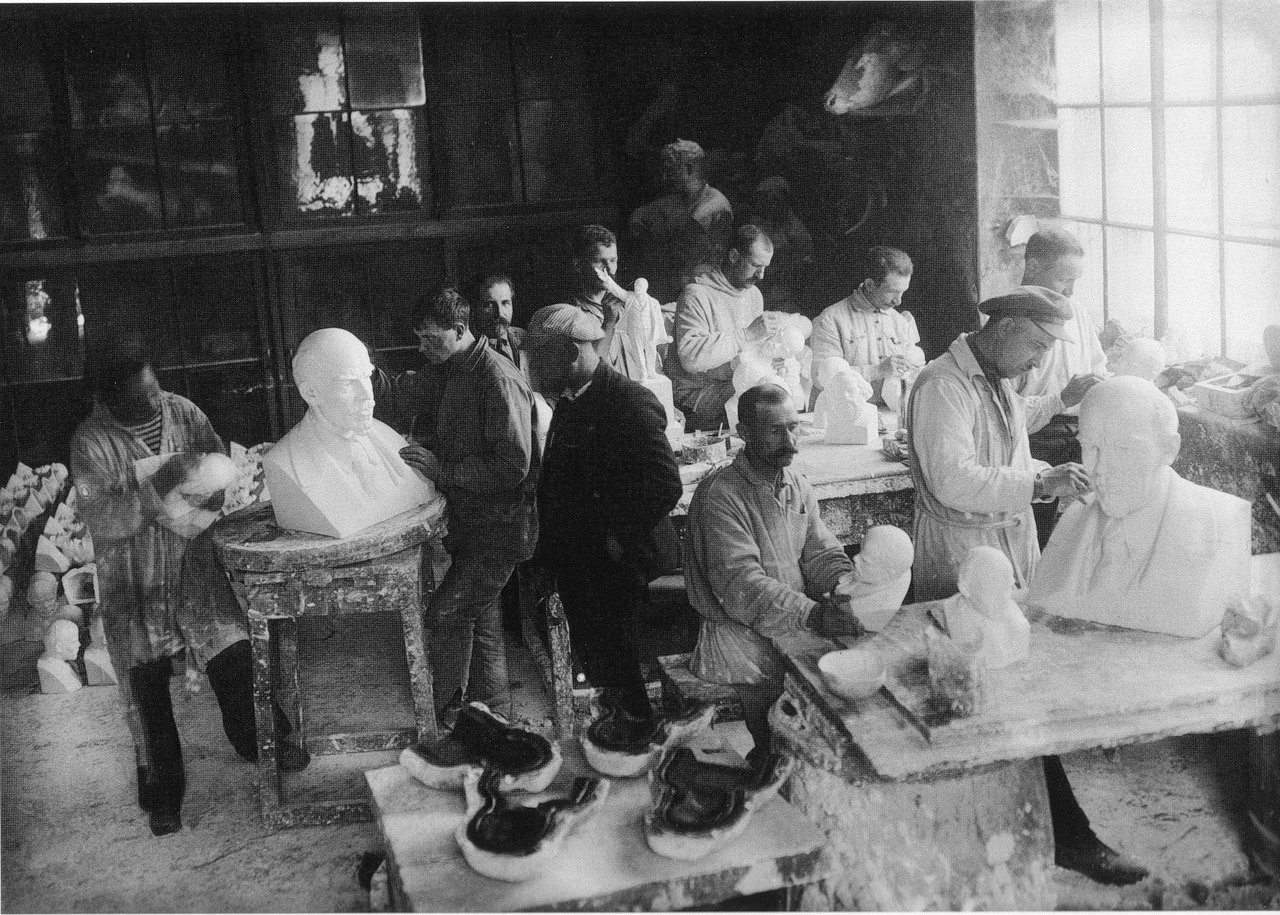

The first manufactories to produce monuments Lenin were set up immediately after his death in 1924, a project spearheaded by the modernist sculptor Sergei Merkurov. Merkurov was educated in Munich and had come under a very strong influence of the Fin de siècle agenda, which ultimately led him to become one of the most prominent creators of death masks of Russian public figures, including Lenin. In the new post-revolutionary reality, it was Merkurov who proposed to launch the mass production of images of Lenin to supply the new Soviet socialist society. His proposal was endorsed by the State Publishing House (Gosizdat) that took care of advertising and distribution of the statues and busts [ 18 ] 18. Khudozhestvennaia zhizhn', 184−185. . Later on this private initiative turned out to be one of the most successful and long-standing commemorative projects. That is why Merkurov’s enthusiasm and his initiative could not but boost the dissemination of the unified Soviet culture and ideology.

1928 saw the establishment of Vsekokudozhnik (The All-Russian Cooperative Association of Artists), a semi-private, semi-public enterprise that laid the groundwork for the socialist artistic industry for many decades to come [ 19 ] 19. Yankovkaia, G. A. Iskusstvo, denigi i politika: sovetskii khudozhnik v gody pozdnego stalinisma. Perm, 2007: 144−165. .

The second reason behind the Soviet government’s endorsement of Merkurov’s initiative was rooted in the ideology of the Soviet economic system of the early 1920s, which gave no hope and left no space to any private art buyers, and at the same time promoted a form of “state capitalist” economy. Lenin died in 1924, at the height of the so-called New Economic Policy, NEP (1921−1928). The system, which had been previously built upon a network of private collectors, overnight became a rigid structure composed of the nationalized manufactories, art collections, and the likе, whose main task was to guarantee continuous supply of ideological goods/productions across the nation. Soviet artists were eager to take part in that new public system of production and distribution that guaranteed regular and secure commissions from the state. After the revolution of 1917 they lost all their patrons and sponsors and by 1920s were obliged to pay considerable taxes since the new state regarded them as “exploiters” – private employers of labor [ 20 ] 20. Silina, Maria. Istoriia I ideologia: monumental’no-dekorativnii reljef SSSR 1920−1930-h godov. Moscow, 2014: 106−107. .

The third reason that prompted the Soviet government to support the distribution of the mass-produced statues of Lenin had to do with the emergence of the new type of socialist, anti-hierarchical system of dissemination of intellectual production. The anonymous character of production, mechanized labor, and the idea of justice and fairness (i.e. unified system of payment), appealed to early Soviet thinkers and artists alike, particularly those that belonged to the Left Front of the Art (LEF), popularized in Western Europe by Walter Benjamin in his 1934 essay Der Autor als Produzent (Artist as Producer). In the words of Benjamin “the rigid, isolated object (work, novel, book) is of no use whatsoever. It must be inserted into the context of living social relations” [ 21 ] 21. Benjamin, Walter. "Artists as Producer." Understanding Brecht. New York, London, 1998: 87. . This was in tune with the Soviet brand of Marxism as well.

New monuments and public images of Lenin created by the Soviet government had to be contextualized. As Benjamin put it in 1936, the technical reproduction of art has no authority of the original which in turn leads to the independence of a reproduced work from the tradition, the ritual and the place, and its existence is based only on politics. Politics has the power to create new traditions and to abandon the old ones. Benjamin compared the dissemination of reproductions with architectural phenomena — building space is something that we get used to through constant repetition [ 22 ] 22. Benjamin, Walter. "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." Art in Modern Culture: An Anthology of Critical Texts. Francis Frascina, ed. London, 1992: 301−302. . This is exactly what happened to the commemorations centering on Lenin: a system emerged that smoothly distributed images and at the same time worked to disconnect them from local or recent political traditions just as smoothly.

The principles of anonymity, standardization and mechanization that characterized the operation of “Vsekokhudozhnik” with its integrated manufactories turning out mass-produced images, sculptures, busts and paintings, defined the socialist method of creation for the anti-hierarchical, and even more importantly, anti-exploitative, anti-predatory socialist culture.

Soon enough, every minute detail of the production process was thoroughly elaborated. Standard contracts were drawn up for the artists that were commissioned to create models for the mass-reproduction in accordance with the production plan and thematic calendars. Standard pricelists were also put together. An original artwork had to be scrutinized by a special commission: in the case of images of Lenin it was The Commission of the CEC (Central Election Commission) of the USSR for the Immortalization of the Memory of V. I Ulyanov-Lenin that was responsible for such an examination. Images of Lenin were among the most expensive works. The fact that there existed a direct correlation between the significance of the subject and the remuneration received by the artist was duly noted (not without a certain wry irony) but many a private diarist as early as 1925 [ 23 ] 23. Yankovskaia, Iskusstvo, denigi i politika, 147; O pamiatnike Leninu, 99. .

By the 1950 both the prices and the themes had been tailored in accordance with an elaborate hierarchy of genres and artists, giving rise to a corrupt system of privileges. Giant factories and industrial plants were key consumers of the mass-produced copies of statues of political leaders, such as Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin (as well as Leon Trotsky and Genrikh Yagoda before both of them fell from grace). These sculptures were needed to inscribe public spaces such as squares, railway stations, workers’ clubs and the like, with visible symbols of the state and the Party.

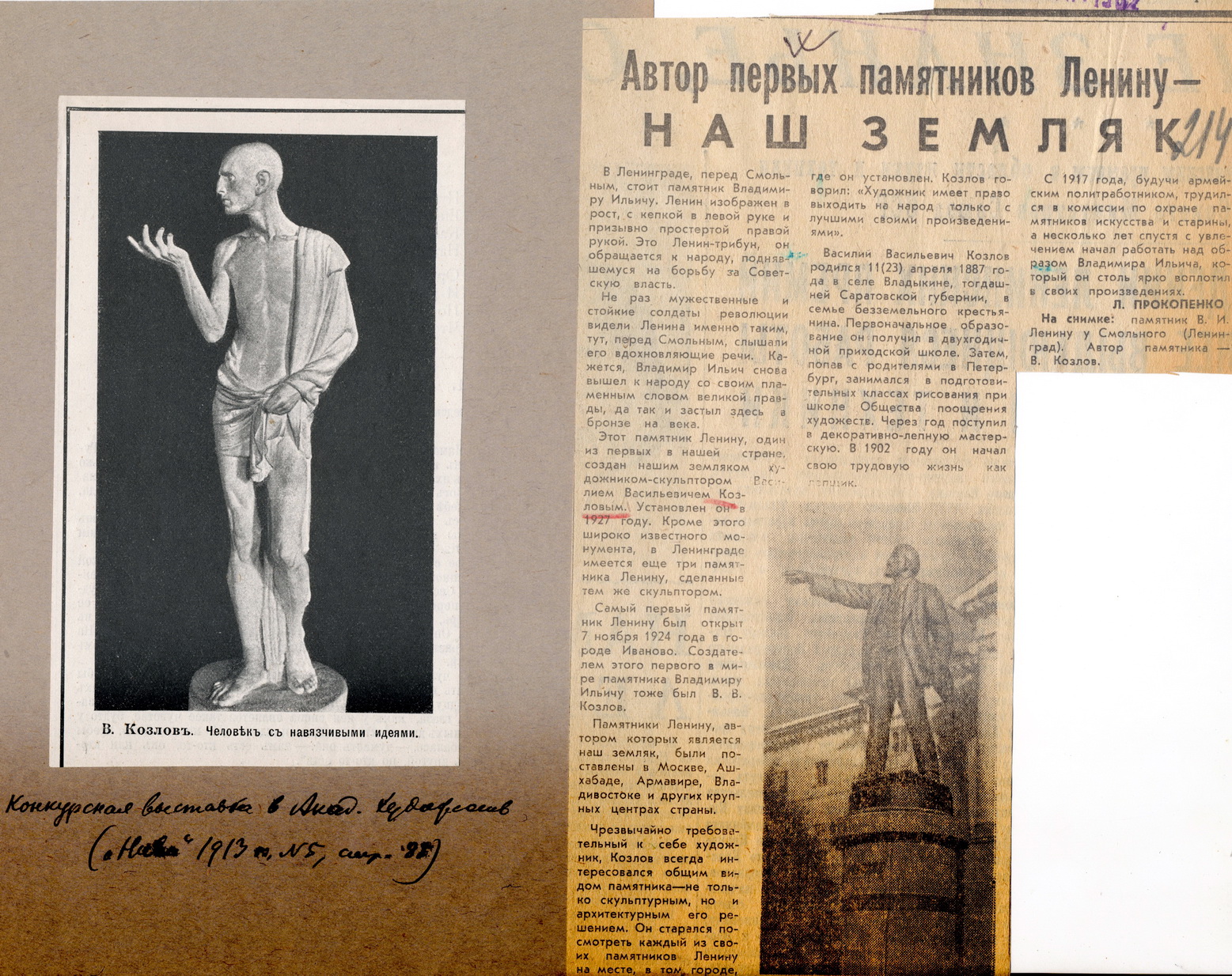

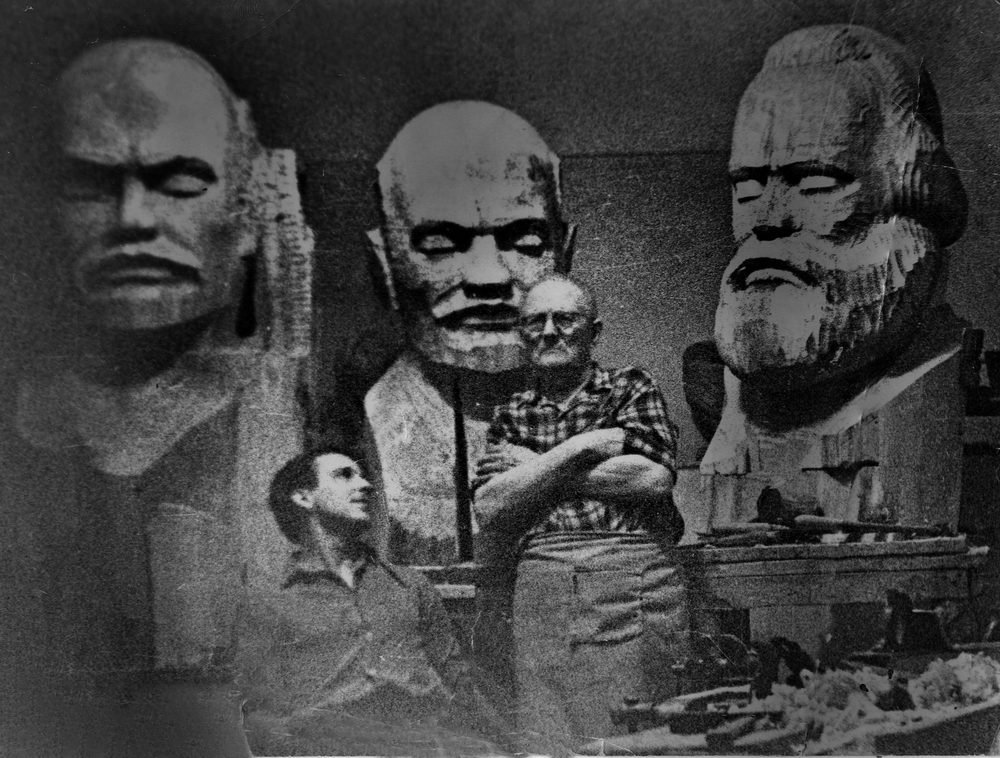

Considering the relatively small number of authorized sculptors entrusted with such commissions (by the mid-1930s their number ranged between five to ten people), the sheer number of copies of monuments produced was staggering. For example, in 1932 Vassily Kozlov, a sculptor, whose carrier had been started by the late Tsarist times created more than 40 public monuments to Lenin and hundreds of busts for Soviet public spaces [ 24 ] 24. Silina, Istoriia i ideologia, 227. . Another popular model designed by Georgy Alekseev and approved by a special state commission was replicated in 10 thousand copies [ 25 ] 25. State archive of Yaroslavl Region. Iz istorii skulpturnoy Leniniany. http://www.yararchive.ru/publications/details/118/ (28 July 2015). . In 1950 the process of replication was brought under regulation: now artists were expected to copy not the original work, but only the pre-approved reference samples or master samples: in effect, we are talking about “copies of copies” here . In his private letter to the People’s Commissar for Education Andrei Bubnov (arrested and purged in 1938) Boris Korolev, one of the most prominent sculptors of the 1930s complained bitterly about the situation in this field: “Over the past fifteen years, opportunism, spiritual poverty, blatant ignorance and the cold empty formality have left ineffaceable traces on all of the widely proliferating sculptures and the entire domain of public art [ 27 ] 27. Boris Korolev. 1888−1963. The State Russian Museum, Almanac. Issue. 205. St. Petersburg: Palace Editions, Graficart, 2008: 74. .”

Indeed, the discrepancy between the works of sculptors, routinely using photographs of Lenin as their reference sources and turning out mass-produced copies of his image on the one hand, and the official policy of the regime that called for authenticity and verisimilitude in sculptural representations of the Bolshevik leader was truly striking [ 28 ] 28. Yankovskaia, Iskusstvo, denigi i politika, 171. . Moreover, with the outset of Stalinist terror party activists eagerly seized on the idea that low-quality mass-production promoted by disgraced functionaries and officials, was really damaging for the Soviet art, an accusation, which was particularly widespread during the purges of 1936−1938 [ 29 ] 29. Russian State Archive for Literature and Arts. Committee on Artistic Affairs. An letter of Sculptors' Union members to Platon Kerzhentsev. Box 2942, 1 Folder 101 (1). P. 86−87. . Yet at the same time, following the annexation of Western Ukraine and Belorussia in 1939, local manufactories were swiftly converted into wholesale mass-production operations. “In Kiev, Kharkov, Dnepropetrovsk, and Lviv these manufactories should have become the hothouses for the creative growth and development of local sculptors. In reality, however, they have been converted into commercial enterprises that focus exclusively on mass production [ 30 ] 30. Russian State Archive for Literature and Arts. Moscow Artists' Union. Box 2943, 1. Folder 2095. P. 28. .”

Vsekohudozhnik was disbanded in 1953, although it had already begun to lose some of its influence back in the late 1930s, when the majority of the most prominent members of the cooperative were arrested and purged. Its property was passed on to the Artistic Foundation of the USSR (Khudfond), which had remained one of the monopolists in the field of art production and distribution up until the collapse of the USSR [ 31 ] 31. Yankovskaya, Iskusstvo, denigi i politika, 160−165. .

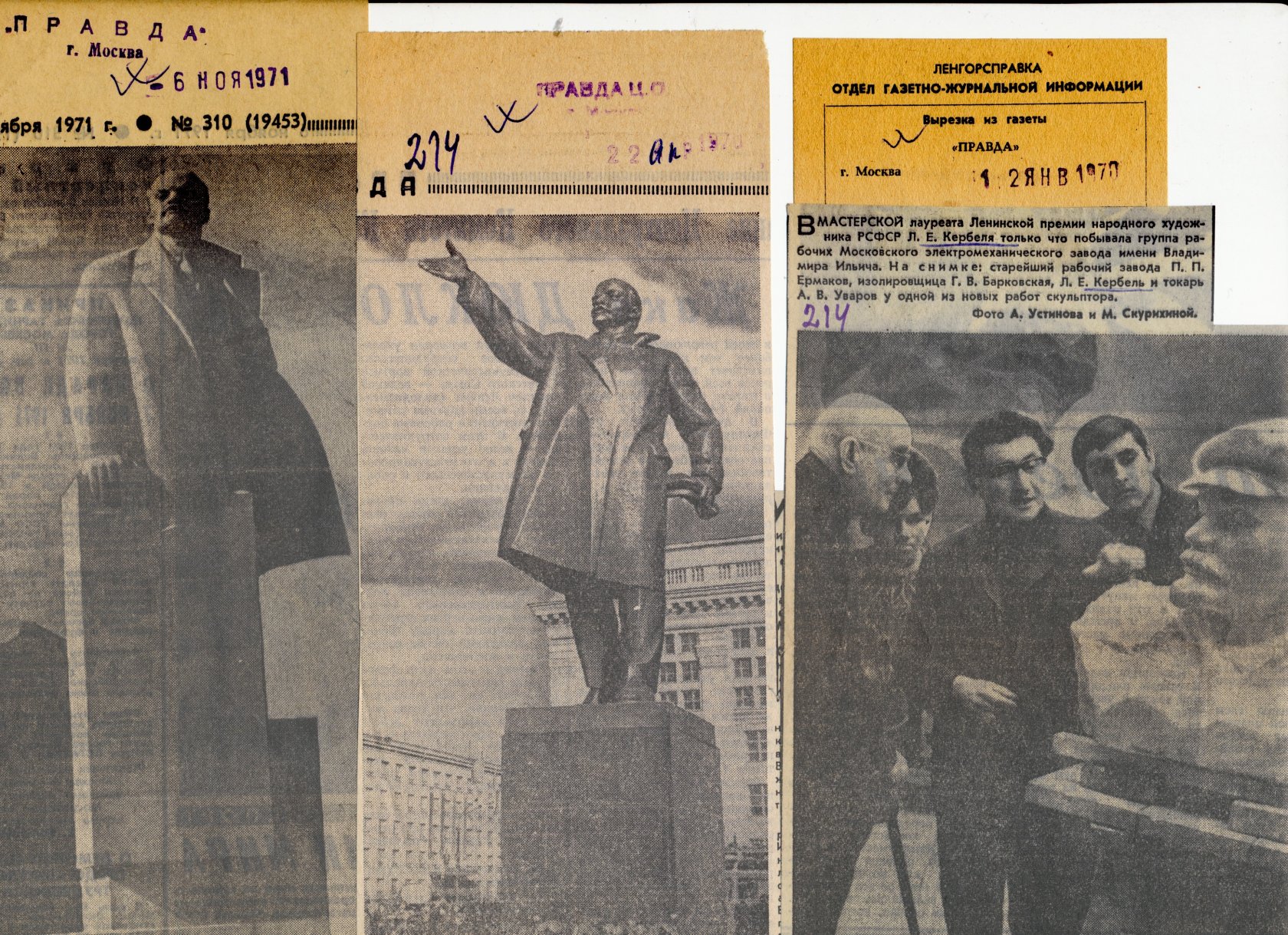

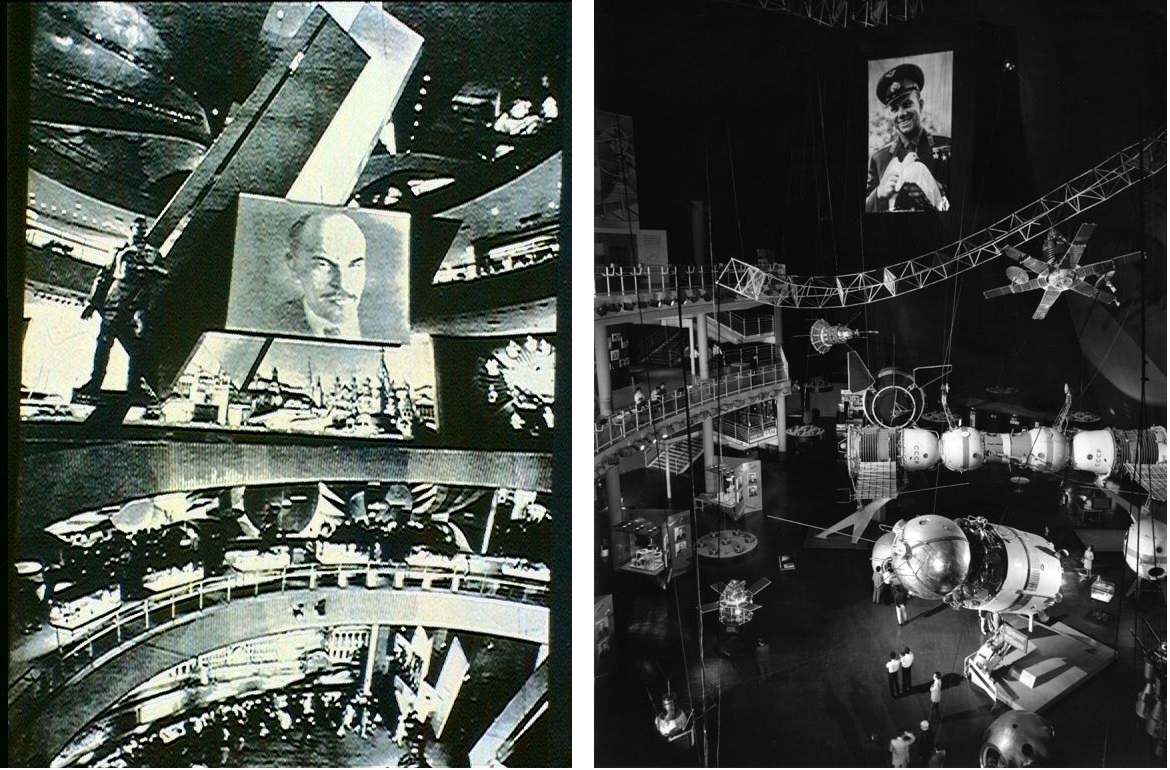

The next important stage in the history of immortalization of Lenin was ushered by the process of destalinization that began in 1954. Criticism of Stalin and his personality cult gave a new impulse to the veneration of Lenin and called for the return to the pure dogmas of Leninism, untainted by the abuses of Stalinism. With renewed vigor traditions and rituals, like guided tours and annual celebrations of revolutionary holidays, including Lenin’s birthday, were reintroduced into the developing infrastructure of public art. The 1967 all-union campaign to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the October revolution of 1917 marked new beginnings of the socialist iconography, that in fact had by 1970 smoothly evolved into the celebrations of the centenary of birth of Vladimir Lenin. In order to discuss the most topical issues pertaining to the celebrations, a special meeting of the Academy of Fine Arts was convened in Moscow on April 23−26, 1969. The meeting was dedicated to monumental sculpture. Urban planners, architects and artists, some of whom were delegates from the fellow socialist countries of the Eastern Bloc, got together to discuss the most urgent and vital problems in the field of public art. However, the enthusiasm evident in some of the speeches and reports presented at the meeting that called for new initiatives and projects did not translate into any significant practical outcome. For instances, while more than twenty monuments to Lenin were erected all across the nation in honor of the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution, some of these monuments were created from the same template [ 32 ] 32. Archive of the Moscow Academy of Arts Library. 26th Session of Moscow Academy of Arts of the USSR. Moscow, 1967: 113−114; about 30 statues, according to Voronov N. V. Sovetskaia monumentalnaia skulptura. 1960−1980. Мoscow, 1984: 133. . Thematically, the range of statues dedicated both to the 1967 anniversary of the Revolution and the 1970 century of Lenin’s birth was rather poor. For instance, out of ten monuments erected in 1967 in honor of the 50th Anniversary of the October Revolution, three were dedicated to Lenin, while the others depicted cosmonauts, a far more popular and relevant topic at the time [ 33 ] 33. Archive of the Moscow Academy of Arts Library. 26th Session of Moscow Academy of Arts of the USSR, 96. .

As a matter of fact, over the course of Soviet history the party activists and artists had failed to come up with a single main monument to the Revolution or to Lenin himself that would have been endorsed by the authorities. This is not to say, however, that there were no attempts at designing such a monument, or that such projects often lacked in ambition. Quite on the contrary. Consider, for example, the monument to Karl Marx, the foundation stone for which in the early 1920s was laid by none other than Lenin himself. Or the notorious Palace of the Soviets (1931−1960) that during the reign of Stalin was considered to be a giant monument to Lenin. Or the enormous monument to Lenin that was supposed to grace Lenin Hills (1958−1970) [ 34 ] 34. On the 1920s monument to Karl Marx see Tolstoy, Khudozhestvennaia zhizhn', 124−128, 190. Palace of Soviets concept: Atarov N. S. Dvorets Sovetov. Moscow, 1940, "Obsuzhdenie konkurskih proektov Dvortsa Sovetov." Arhitektura SSSR. 1960. № 1, 39; on monument to Lenin in Moscow: Kovalev A. Geniiu Revolutsii. Architektura SSSR, 1960, 4: 7−17. . A large-scale museum to Lenin was inaugurated in 1970 in his birth-city of Ulyanovsk, while a more modernist museum in Gorki Leninskiye was not opened up until 1987, that is to say, right before the collapse of the Soviet Union, although initially it was supposed to be opened in the 1960s [ 35 ] 35. Rozanov, E. G. Arhitektura muzeev V. I. Lenina. Moscow: Stroyizdat. 1986: 26−76; 90−182. .

The 1960s — 1970s saw the rise of a new interpretation of the image of Lenin [ 36 ] 36. Archive of the Moscow Academy of Arts Library. 26th Session of Moscow Academy of Arts of the USSR, 121; Voronov, Sovetskaia monumentalnaya skulptura, 103.f . Sculptors and artists resorted to a more laconic, simplified rendition of his body, typical of late modernism, although Lenin’s face was still to be portrayed with realistic precision. Consider, for example, Lev Kerbel’s 1959 monument to Lenin in Gorki Leninskiye or Nikolay Tomsky’s post-cubist monument to Lenin that was erected in Berlin in 1970. Sites associated with the life of Lenin were described in the special genre of popular literature and in books on regional history and cultural geography. A typical example of that kind of literature is a book by Mark Etkind titled Lenin Addresses the Crowd from the Top of an Armored Car (1969). Half of it deals with the history of this particular commission and documents the process of creation of the monument, while the second part is a detailed and richly illustrated story of the everyday present condition of the monument placed in the context of multiple national holidays, guided tours and the like [ 37 ] 37. Etkind, Mark. Lenin govorit c bronevika: Pamyatnik V. I. Leninu u Finlyandskogo vokzala v Leningrade, Leningrad, 1969: 71. . The majority of monuments to Lenin erected in larger Soviet cities and republican capitals were produced by the sculptors who had become quite well known during the reign of Stalin, such as Matvei Manizer, Evgenii Vuchetich, or Veniamin Pinchuk [ 38 ] 38. Voronov, Sovetskaia monumentalnaia skulptura, 104, 126−128. . With the exception of several artistic innovations, that soon enough became banal and worn out by the massive scale of copying and reproduction, local Unions of Artists remained faithful to the same iconographic type, that was successfully introduced in the late 1930s. By 1990 the number of public monuments to Lenin in the Russian Soviet Federal Republic alone reached a staggering figure of seven thousand monuments [ 39 ] 39. Skol’ko vsego pamyatnikov Leninu? http://leninstatues.ru/skolko (27 July 2015). .

The final stage in the history of immortalization of Lenin coincided with the collapse of the Soviet system in 1989. Its outset was marked by the real and metaphorical iconoclasm, the fight against all sorts of images of Bolshevik leaders. Later on, memorial sites and monuments to Lenin were simply forgotten and abandoned [ 40 ] 40. Gamboni, Dario. "The Fall of the 'Communist Monuments'" The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution. New Haven, 1997. 51−90; Kattago, Siobhan. Memory and Representation in Contemporary Europe the Persistence of the past. Burlington, VT, 2012. On Lenin Cult: Smith TJ. "The Collapse of the Lenin Personality Cult in Soviet Russia, 1985−1 995." Historian. 2006. Vol. 60, issue 2. P. 325−343. . In Russia, which was the ground zero for the political testing and expansion of communism, the process of reexamination of Lenin’s political legacy and consequently, of the role and function of his monuments within the context of contemporary cities proved highly ambiguous. Images of Lenin used to figure too prominently in the field of Soviet public art and for too long a period to be easily forgotten. Monuments to Lenin that still tower over many a central square in towns and cities all across the country, still function as important landmarks or tourist magnets, drawing crowds of both visitors and residents up to this day. Think, for example, of the giant monument to Lenin on Kaluzhskaya (former Oktyabrskaya) square in Moscow created by Lev Kerbel in 1985, or a monument on the eponymous square in Saint Petersburg (that monument was designed by Sergei Evseev in 1926). These and other monuments still receive a lot of attention from art critics and tourists.

According to statistics, the majority of monuments [to Lenin] that have survived up to this day in Russia are located in the nation’s capital: a total of 103 sculptures [ 41 ] 41. See: Statistics of Lenin monuments: http://leninstatues.ru/skolko (20 July 2015). According to the latest news, there survived more than 8500 monuments in the world. . Mass-produced political public art from the Soviet era is now preserved in two locations. One is the specially designed park of Soviet sculpture Muzeon in Moscow, the only park of this kind in the country. The other is the ROSIZO Museum that has been assembling a sizable collection of socialist realist art, including political sculpture, since the 1940s [ 42 ] 42. Sotsrealizm: inventarizatsiya arkhiva: iskusstvo 1930−1940-h godov: iz sobraniya Gosudarstvennogo muzeyno-vystavochnogo tsentra ROSIZO: [Z. I. Tregulova, F. M. Balakhovskaya]. Sankt-Peterburg: Gos. muzeyno-vystavochnyy tsentr ROSIZO, 2009: 71 . The way each monument is contextualized largely depends on its location and status. As is the case with the Lenin’s Mausoleum located at the heart of Moscow’s Red Square (e. g. Mausoleum was hidden behind special ornamental boards during the V-Day parade in Moscow in May 2014). Some of the [Soviet-era] monuments still occupy key locations on the central squares of Moscow and Saint Petersburg. Others fall off the radar and become largely ignored by those whose job it is to preserve cultural and historical heritage, since these monuments are now believed to be of “mediocre” artistic and dubious historical value.

Other experts argue, that there is no pressing need to preserve these monuments since throughout the Soviet period, they used to be replicated in numerous copies all across the former Soviet space [ 43 ] 43. Architectural heritage http://riarealty.ru/news/20 140 124/402 391 669.html (20 July 2015); Alena Lapina. "Goodbye, Lenin!" http://www.theartnewspaper.ru/posts/1736/ (20 July 2015) . Still others believe that it is possible to disregard the political connotations of these monuments and to transform the numerous monuments to Lenin into de-politicized “dedushkas” or “eudemons” in order to turn political hallmarks into tourist attractions or important sites for the local communities that can be used for public celebrations and the like [ 44 ] 44. Marina Khrustaleva. Regiony ischut novie smysly, magnity i brendy. http://www.vedomosti.ru/realty/articles/2015/04/20… (20 July 2015). . Another important trend is also worth mentioning in the discussion of the post-Soviet interpretations of the cult of Lenin. One of the latest Lenin museums in the Soviet Union, the Krasnoyarsk Museum Center, has been converted into a Center for Contemporary Art and has incorporated the exhibition dedicated to the October revolution that it had inherited from the Soviet times into an exhibit and heritage object [ 45 ] 45. Konkurs na khudozhestvenno-proyektnuyu kontseptsiyu ekspozitsii "V zazorakh ideologii" /Muzeynyy tsentr "Ploshchad' mira." Krasnoyarsk. http://mira1.ru/event/495 (5 March 2017). . However, there is no comprehensive cohesive strategy behind these disjointed processes and initiatives, which partially explains why they largely miss the point. As I have sought to argue earlier, the very infrastructure of production and distribution of commodified Lenin’s images across the Soviet domain is in itself a fascinating legacy that should be preserved and promoted as one of the most impressive projects of Soviet modernist culture.

The Soviet system has elaborated very specific and clear-cut criteria that staked the boundaries of the so-called high-brow sophisticated culture. It also promoted the prestige of education in the field of liberal arts, so that the public space filled with works of art was considered to be a part of the natural habitat of a homo Sovieticus [ 46 ] 46. ankovskaya, Isskustvo, den’gi i politika, 155−158. . The ambiguity and inner inconsistency of this habitat was reflected in the fact that regardless of the high status of arts and the prestige bestowed on it by the regime, Soviet artists had to create portraits of the leader based on his photographs and to do it under the scrupulous eye of numerous censors and controlling agencies, while ordinary citizens and city dwellers were forced into urban public spaces filled with second-rate copies of these portraits. Today this issue of discrepancy between the status of art and the socialist artistic industry in the USSR prompts historians to seek other way to analyze public art in the context of the absolute and total historization of public space [ 47 ] 47. Maria Silina. Obschestvennoe dostoianie kak travma. http://www.colta.ru/articles/art/13 464 (5 March 2017) .

This article is based on a conference paper delivered in September 2015: Maria Silina, “Memorial Industry: V. I. Lenin Commemoration in Soviet Russia from 1924 until today.” International Conference “Sites of Memory of Socialism and Communism in Europe”, Bern, Switzerland.

- Memory as commodity was analyzed by Andreas Huyssen in his Twilight Memories: Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia. London, 1995.

- Tumarkin, Nina. Lenin Lives!: The Lenin Cult in Soviet Russia. Cambridge, 1983; Ennker, Bruno. Die Anfänge des Leninkults in der Sowjetunion. Köln, Wien, 1997.

- With a notable exception: a case study of Latvian art production by Sergei Kruk. "Profit rather than politics: the production of Lenin monuments in Soviet Latvia." Social Semiotics. 20:3. (2010): 247−276.

- More on the Lenin Institute in Mosolov, V.G. IMEL: Zitadel Partiinoy Ortodoksii. Iz istorii Instituta Marskizma-Leninizma pri ZK KPSS, 1921−1956. Moscow, 2010: 107−184. On initial projects of Lenin Museum: "Muzei Vladimira Ilicha." Pravda. 23 Aug. 1923: 3.

- Shefov, A. N. Leniniana v sovetskom izobrazitel’nom iskusstve. Moscow: 1986: 82−89.

- Khudozhestvennaia zhizhn' Sovetskoi Rossii. Tolstoy V. P., ed. 1917−1932. Sobitiia, fakti, kommentarii. Sbornik materialov i dokumentov. Moscow, 2010: 170−172.

- On the early history of building Lenin museums see: Rozanov E. G., Reviakin V. I. Arhitektura muzeev V. I. Lenina. Moscow, 1986: 7−25.

- O pamiatnike Leninu. Leningrad, 1924: 21−33, Khudozhestvennaia zhizhn', 173−176.

- Khudozhestvennaia zhizhn', 191−192.

- Meeting of Lenin’s commemorational commission in Ulianovsk. 5 March 1938. Russian State Archive for Literature and Arts, Moscow. Box 962, 3, Folder 422. P. 26.

- Meeting of Lenin’s commemorational commission in Ulianovsk. 5 March 1938. Russian State Archive for Literature and Arts, Moscow. Box 962, 3, Folder 422. P. 22.

- Lénine album. Cent photographies. Composé par V. Goltzeff. Moscou, 1927.

- Rabinovich, I. S. Lenin v izobrazitel’nom iskusstve. Moscow, Leningrad, 1939.

- Lenin. Collection of photographs and stills. In 2 vols. Moscow, 1970: 7−15.

- Boiko, A. A. "Sotsial'no-politicheskii avtorskii plakat 1980-h godov i iskusstvo sots-arta: osobennosti, obshee i razlichiia." Neofitsial’noe iskusstvo v SSSR. 1950−1980-e gody. Moscow, 2014: 361−370.

- Michalski, Sergiusz. Public Monuments: Art in Political Bondage, 1870−1997. London: Reaktion, 1998. 13−55.

- Huyssen admits that he drew the notion of "imagined memory" from Arjun Appadurai’s discussion of "imagined nostalgia" in his Modernity at Large (1996). Huyssen, Andreas. Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory. Stanford, 2003. 166.

- Khudozhestvennaia zhizhn', 184−185.

- Yankovkaia, G. A. Iskusstvo, denigi i politika: sovetskii khudozhnik v gody pozdnego stalinisma. Perm, 2007: 144−165.

- Silina, Maria. Istoriia I ideologia: monumental’no-dekorativnii reljef SSSR 1920−1930-h godov. Moscow, 2014: 106−107.

- Benjamin, Walter. "Artists as Producer." Understanding Brecht. New York, London, 1998: 87.

- Benjamin, Walter. "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." Art in Modern Culture: An Anthology of Critical Texts. Francis Frascina, ed. London, 1992: 301−302.

- Yankovskaia, Iskusstvo, denigi i politika, 147; O pamiatnike Leninu, 99.

- Silina, Istoriia i ideologia, 227.

- State archive of Yaroslavl Region. Iz istorii skulpturnoy Leniniany. http://www.yararchive.ru/publications/details/118/ (28 July 2015).

- Yankovskaia, Iskusstvo, denigi i politika, 171.

- Boris Korolev. 1888−1963. The State Russian Museum, Almanac. Issue. 205. St. Petersburg: Palace Editions, Graficart, 2008: 74.

- See: Russian State Archive for Literature and Arts. Moscow Artists' Union. Iosif Chaikov. On Art Industry and Mass Sculpture. 27 November 1940. Box 2943, 1. Folder 2096. P. 3−24

- Russian State Archive for Literature and Arts. Committee on Artistic Affairs. An letter of Sculptors' Union members to Platon Kerzhentsev. Box 2942, 1 Folder 101 (1). P. 86−87.

- Russian State Archive for Literature and Arts. Moscow Artists' Union. Box 2943, 1. Folder 2095. P. 28.

- Yankovskaya, Iskusstvo, denigi i politika, 160−165.

- Archive of the Moscow Academy of Arts Library. 26th Session of Moscow Academy of Arts of the USSR. Moscow, 1967: 113−114; about 30 statues, according to Voronov N. V. Sovetskaia monumentalnaia skulptura. 1960−1980. Мoscow, 1984: 133.

- Archive of the Moscow Academy of Arts Library. 26th Session of Moscow Academy of Arts of the USSR, 96.

- On the 1920s monument to Karl Marx see Tolstoy, Khudozhestvennaia zhizhn', 124−128, 190. Palace of Soviets concept: Atarov N. S. Dvorets Sovetov. Moscow, 1940, "Obsuzhdenie konkurskih proektov Dvortsa Sovetov." Arhitektura SSSR. 1960. № 1, 39; on monument to Lenin in Moscow: Kovalev A. Geniiu Revolutsii. Architektura SSSR, 1960, 4: 7−17.

- Rozanov, E. G. Arhitektura muzeev V. I. Lenina. Moscow: Stroyizdat. 1986: 26−76; 90−182.

- Archive of the Moscow Academy of Arts Library. 26th Session of Moscow Academy of Arts of the USSR, 121; Voronov, Sovetskaia monumentalnaya skulptura, 103.f

- Etkind, Mark. Lenin govorit c bronevika: Pamyatnik V. I. Leninu u Finlyandskogo vokzala v Leningrade, Leningrad, 1969: 71.

- Voronov, Sovetskaia monumentalnaia skulptura, 104, 126−128.

- Skol’ko vsego pamyatnikov Leninu? http://leninstatues.ru/skolko (27 July 2015).

- Gamboni, Dario. "The Fall of the 'Communist Monuments'" The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution. New Haven, 1997. 51−90; Kattago, Siobhan. Memory and Representation in Contemporary Europe the Persistence of the past. Burlington, VT, 2012. On Lenin Cult: Smith TJ. "The Collapse of the Lenin Personality Cult in Soviet Russia, 1985−1 995." Historian. 2006. Vol. 60, issue 2. P. 325−343.

- See: Statistics of Lenin monuments: http://leninstatues.ru/skolko (20 July 2015). According to the latest news, there survived more than 8500 monuments in the world.

- Sotsrealizm: inventarizatsiya arkhiva: iskusstvo 1930−1940-h godov: iz sobraniya Gosudarstvennogo muzeyno-vystavochnogo tsentra ROSIZO: [Z. I. Tregulova, F. M. Balakhovskaya]. Sankt-Peterburg: Gos. muzeyno-vystavochnyy tsentr ROSIZO, 2009: 71

- Architectural heritage http://riarealty.ru/news/20 140 124/402 391 669.html (20 July 2015); Alena Lapina. "Goodbye, Lenin!" http://www.theartnewspaper.ru/posts/1736/ (20 July 2015)

- Marina Khrustaleva. Regiony ischut novie smysly, magnity i brendy. http://www.vedomosti.ru/realty/articles/2015/04/20… (20 July 2015).

- Konkurs na khudozhestvenno-proyektnuyu kontseptsiyu ekspozitsii "V zazorakh ideologii" /Muzeynyy tsentr "Ploshchad' mira." Krasnoyarsk. http://mira1.ru/event/495 (5 March 2017).

- ankovskaya, Isskustvo, den’gi i politika, 155−158.

- Maria Silina. Obschestvennoe dostoianie kak travma. http://www.colta.ru/articles/art/13 464 (5 March 2017)