primordial backgrounds to self-institutionalisation in russian art

On the occasion of the exhibition ‘Museum of Pictorial Culture. To the 100th Anniversary of the First Museum of Contemporary Art’, which took place at the State Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow), Alessandra Franetovich has explored primordial backgrounds to self-institutionalisation in Russian Art.

In 1918, a group of avant-garde artists active in Moscow and Saint Petersburg joined forces to create an experimental format for a process of musealisation, almost completely self-organised, which culminated in creation of the museums of pictorial culture in 1919. The New Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow organised a research-based exhibition to celebrate the centenary of this event, reformulating for a wider audience a story that had previously been little known beyond a small circle of specialists, focusing particularly on the Moscow input to the experience – Moscow Museum of Pictorial Culture. If the importance of this historical reconstruction per se is undeniable, it also enabled a more complex and deeper understanding of the avant-garde movement by presenting the best-known section of the New Tretyakov collection in a brand new light. This revision challenged the status of the museum as a ‘dead’ institution, bound by established canons, and applied different critical principles to its historical collection in a process that I would like to call ‘institutional self-critique’. This formulation refers to the tendency that some institutions are developing, as an attempt to reflect on their own collections and practices with the aim of de-colonising, de-constructing, and self-criticising their own approach and history. This stage can be intended as the development of the ‘institutional critique’, which has been consciously enacted by artists since the 1960s, and that has already been absorbed by the narration and methods of current art history as a pivotal moment in the art system.

Reconstruction of the history and context of the museums of pictorial culture has the potential to open up awareness of formats of self-organisation in more recent decades, some of them made in conjunction with established institutions. For the retrospective look that is applied in the present text (which will be too concise to tackle such a demanding and complex topic in detail) it is moreover interesting that the history of the Moscow Museum of Pictorial Culture can be interpreted as an early attempt at self-organisation and self-institutionalisation in the history of Russia and the USSR, where there would be further use of this strategy in the development of contemporary art history in the following decades. It is further possible to see the inclusion of administrative tasks in the artists’ practice as a preliminary influence on the art world of the bureaucratisation process, which was typical of the 20th century. This view has already been formulated for some unofficial Soviet artists who, active since the 1960s, organised their own events and exhibitions in private spaces, and implemented self-archiving and self-historicising practices. Consequently, in order to properly shed a light on the self-organisation practices enacted by avant-garde artists, it is fundamental to contextualise this experience in the whole history of Russian contemporary art. However, several problematics arise: how the concept of self-institutionalisation, with all its current meanings and readings, can be applied to a previous era without falling into the error of wrong attribution. Can our contemporary understanding of self-organisation, through a retro-imposed filter, help us to bring out nuances in the story of the museums of pictorial culture?

Self or non self-organisation?

In the aftermath of the October revolution, the entire social structure in Russia, including the domain of art and culture, was mobilised by the State for the cause of Sovietisation. Many artists responded to this new deal with enthusiasm and played an active role in it at the same time as they were conceiving and creating artworks that are today recognised as some of the most important masterpieces of Russian art. In the multitude of artistic researches that shaped the polyphony of the Russian avant-garde the recurrent theme and concept was: ‘new’. Appearing in countless written records of the era, used in reference to many different proposals and in diverse contexts, the category of the new was intended to be something that would be used to construct, piece by piece, a not-so-distant future society.

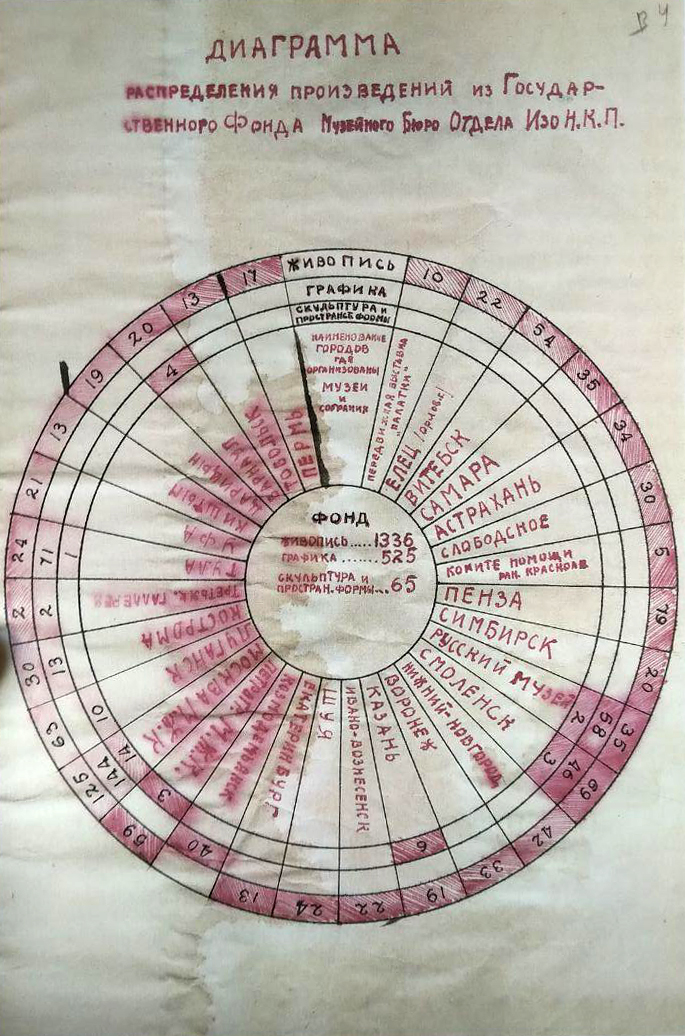

As conceived in 1918, the museums of pictorial culture were to have one central site in Moscow and 13 other venues in various Russian cities including Voronezh, Vitebsk, Samara, and Penza. [ 1 ] 1. Zgur V. V., ed. The Museum for Painting Culture at Rozhdestvenka Street, 11 // Museums and Places of Interest in Moscow. Moscow: Moscow Municipal Economy Printing House, 1926. P. 82–85. In: Zhilyaev A., ed. Avant-Garde Museology, e-flux classics and V-A-C: New York, Moscow, 2015. P. 624. At the beginning, the name was slightly different: and museums of artistic culture was transformed into museums of pictorial culture in order to accord pride of place to painting. The project arose from a series of events that took place in the ‘revolutionary’ transition period, when the approach to art and culture applied by Anatoly Lunacharsky, the Soviet People’s Commissar for Education (acronym, Narkompros), and particularly by the IZO (acronym of the Department of Fine Arts of the Narkompros), was implemented as part of a broader organisation and systematisation of the cultural scene based on the new principles of the post-revolutionary era. In a moment characterised by the abolition of private property and the nationalisation of goods, a huge amount of artworks was put at state disposal. Many of them were taken from outstanding private collections, such as that of the brothers Sergei and Pyotr Shchukin, and of Ivan Morozov, while others came from Lunacharsky’s initiative to purchase the most interesting pieces of avant-garde art from the artists themselves. The requisitioning of artworks was organised through legal but nevertheless compulsory purchases, and was often driven by the artists themselves. It is therefore possible to assume that the museums of pictorial culture constituted an experience of shared responsibility between official institutions and artists, who often also assumed administrative tasks (particularly in the period from 1919 to 1922).

The involvement of artists officially began in 1918, when a commission was set up to oversee first organisational steps and there were several meetings of artists to discuss collectively the methods and the purposes of the project. Outcomes of the discussions were set down in texts signed by artists, including the Report on a Museum of Contemporary Art by Vladimir Tatlin and Sofia Dymshits-Tolstaia. [ 2 ] 2. Tatlin V., Dymshits-Tolstaia S. Report on a Museum of Contemporary Art. 28 July 1918. URL: http://www.incorm.eu/documents.html#a1918. It was drawn up following a discussion on 28 July 1918 by the Narkompros Artistic Collegium and Moscow Artistic Collegium, and proposed a list of theoretical and practical principles to be followed. Much attention was given to criteria for the selection of artworks to constitute the collection, a process that was to be detached from any issues of ‘personal taste’. This concept was judged to be a category of the past, i.e. a method that concealed a traditional and conservative approach. Instead, a committee named Artistic Collegium resolved to use its knowledge to help make the selection more appropriate.

The new art

In a context characterised by heterogeneity of artistic researches, the topic of ‘the new’ had the role to reunite such diversity: thus the creation of a new institution, that could host and display the new kind of art that new artists were creating, was the solution. The Tatlin-Tolstaia text clearly stated commitment to pursue a selection process that would single out the most interesting coeval production, regarding which no established art critics or museological figures could give better advice. Moreover, the selection was to be of artists’ names, while the final choice of artworks would be carried out by the nominated artists. Finally, it was decided to keep a record of the names of collectors, from whom works or entire collections had been requisitioned, in order to trace provenance, a decision which shows commitment to keeping historical vestiges and sensibility towards the historicisation process around the artworks.

Since the art was new, the methods used to decide what was innovative and what was not also had to be new. The need for self-organisation was part and parcel of the attack on established institutional methods and the ending of reliance on museum professionals and art critics, who were blamed for not understanding the latest artistic researches in Russia. In several writings, such as those by Olga Rozanova, and Kazimir Malevich, artists accused ‘czarist’ curators of cowardice and of insulting revolutionary art. In particular, Malevich put into words a vision composed of two opposed sides – conservative and innovative – that could not be reconciled: ‘Due to conditions generated by refined connoisseurs, the creations of the innovators were shoved back into cold garrets and miserable studios where they awaited their fate, being abandoned to destiny’. [ 3 ] 3. Malevich K. The Axis of Colour and Volume // Izobrazitelnoe iskusstvo [Plastic Arts], №1, Petrograd, 1919. URL: http://www.incorm.eu/documents.html#a1918.

Malevich poured scorn on the different scale of value attributed to institutionalised artists, such as Vrubel, or foreign artists such as Cézanne, Van Gogh and Picasso, highlighting the centrality of the concept of time in the evaluation process used by professionals: ‘They have established time as a barometer of understanding. When a work wallows in the monstrous and inept brain of public opinion for an impressive number of years, then this work that has not been eaten but soiled by the saliva of society is accepted in the museum. It is recognized. This is the fate of innovators.’ [ 4 ] 4. Ibid.

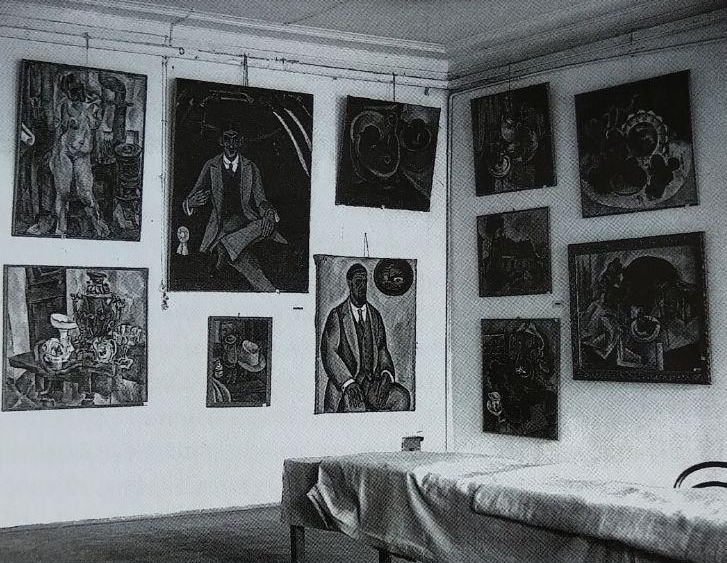

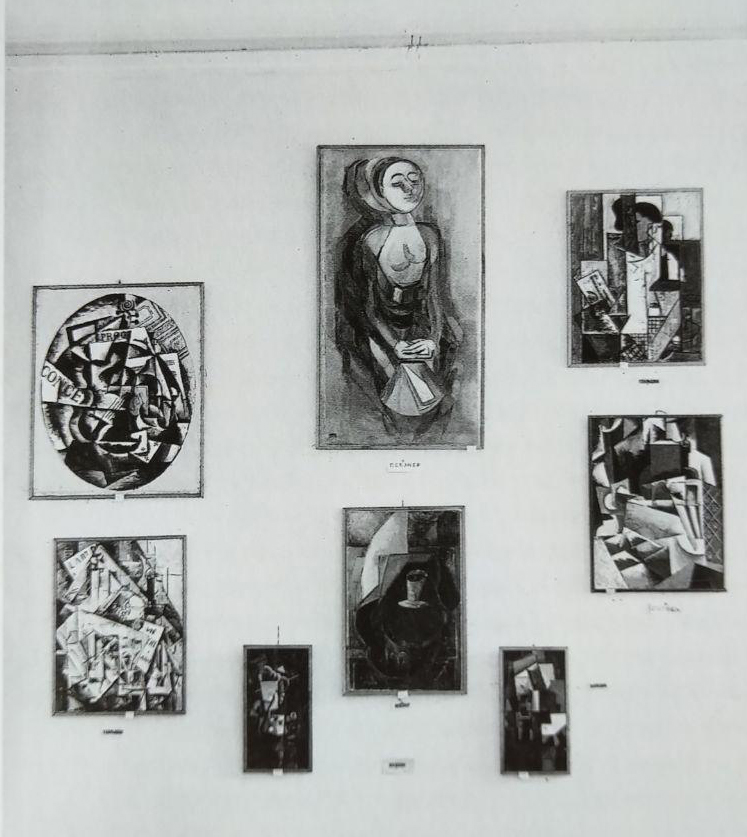

The dichotomy between ‘old’ and ‘new’ grew gradually in the eyes of the artists. On one side, the museum professional was deemed to be an archaeologist only able to deal with the past, and found guilty of Russia’s conservatism. On the other hand, the pioneering ideas of the revolutionary artists extended also to a new conception of the display of artworks. Even if the works were still predominantly hung on walls (in a pure gesture that demonstrated respect for the canonical perception of the pictorial dimension), they were to be organised in rooms that did not follow a chronological order. As reproduced in the exhibition at the New Tretyakov Gallery, the display was conceived as a tour through rooms dedicated to different artistic groups, but giving special attention to the contrast of shapes and rules of construction. This approach is clearly seen in the article ‘The museum of painting culture at Rozhdestvenka street, 11’ published in the guide Museums and Places of Interest in Moscow in 1926 (after the Museum had already closed). The text describes how each room was organised to show representative pieces of the most recent and experimental researches of the period. The distinction of periods and the fundamental role of time in the dissection of the true was thus negated, breaking with tradition and asserting a new rationale behind the preservation and display of these works, which had not been welcome before in established institutions. The materiality of the artwork and of art work would overcome the concept of linear time.

The challenge to the traditional role of time in the presentation of works of art was matched by a new approach to space, as manifest in the decision to create a network of museums of pictorial culture across Russia, covering different geographies and territories. The centripetal force that for many years had been characteristic of coeval contemporary art, as it was increasingly drawn to the biggest European cities, was thus negated. A more horizontal approach was put in opposition to the vertical model of art history (still predominant nowadays), aiming to spread knowledge in remote regions of the country, contributing to the creation of a less peripheral landscape. This aspect deserves more attention as a preliminary and authentic turn towards the local sphere, addressing a currently existent dualism between the two domains of the global and the local, although today’s critical discourse plays out this dichotomy in a quite different scenario and between different subjects, through questions of nationality in a reality that tends towards the fading of geographical borders while erecting new theoretical ones. In the vast spaces of Soviet Russia, shortly after the revolution and in line with the goal of constructing an egalitarian society, museums had to be spread far and wide so that everybody who worked outside the city centre, or in smaller cities, and also the ‘peasants and workers’, could have access to culture, as clearly stated in the preparatory documents for the museums of pictorial culture.

As David Shterenberg, the IZO director, wrote: ‘The concept of artistic culture contains, in accordance with the very meaning of the word “culture” as a dynamic activity, a creative element; creative work presupposes creation of the new, invention: artistic culture is nothing other than the culture of artistic invention.’ [ 5 ] 5. Shterenberg D. The Museum of Artistic Culture // Report on the Activities of the Department of Plastic Arts of Narkompros, May 1919 // Izobrazitelnoe iskusstvo [Plastic Arts], №1, Petrograd, 1920. URL: http://www.incorm.eu/documents.html#b-1919.

This concept of dynamism naturally implied the opening of more venues and the plan for a network of institutions across the country, around which art collections would travel. This was the same motivation that gave rise to the agit-train and Okna ROSTA posters, which used the media of transport and of communication, respectively, as tools of Soviet propaganda. More museums in more cities would facilitate the circulation of artworks and the diffusion of knowledge about the new art.

For the democratisation of art

As director of the Moscow Museum of Pictorial Culture, a position he held from 1919 to 1920, Wassily Kandinsky stated the need for unconventional methods as well as new principles for the selection of artworks. These should be ‘new contributions of a purely artistic nature, i.e., the invention of new artistic methods’, and ‘the development of purely artistic forms, independent of their content, i.e., the element, as it were of craft in art.’ [ 6 ] 6. Kandinsky W. Khudozhestvennaia Zhizn [Artistic Life]. Moscow, 1920 // Kenneth C. L., Vergo P., eds., in Kandinsky.Complete Writings on Art, Vol. 1 (1901–1921), Editors (London: Faber and Faber, 1982, P. 437–444). In his opinion, attention to problems connected with shapes, as well as a more generic approach to the tangible elements of artistic practice would reveal the ‘need to struggle painstakingly with the purely material aspect of his work, with technique – all this has placed the artist, as it were, above and beyond the conditions that determine the life of the working man.’ It was thus fundamental to spread proper understanding of the profession of the artist who ‘creates works of real value and demonstrates his definitive right to take, at the very least, equal place among the ranks of the working population.’ This egalitarian aspiration was summed up in Kandinsky’s term ‘democratisation of art’, a locution that he used in the belief that such a goal could be fully attained through the active involvement of artists in all the processes of art management. [ 7 ] 7. Ibid.

Speaking against the old anachronism that marked the choice of previous cultural operators, Aleksandr Rodchenko, who assumed the directorship of the Museums of Pictorial Culture from 1921 to 1922, said that artists are ‘the only people with a grasp of the problems of contemporary art and as the creators of artistic values, are the only ones capable of directing the acquisition of modern works of art and of establishing how a country should be educated in artistic matters.’ [ 8 ] 8. Rodchenko A. Declaration on Museum Management // Izobrazitelnoe iskusstvo [Plastic Arts], №1, Petrograd, 1920. URL: http://www.incorm.eu/documents.html#a1918. The polysemic vision translated into multidisciplinary and helped to determine a reflection on the practice of research, too. In fact a fundamental part of the project was collecting an interesting number of publications, organised in a library, whose importance was also shown in the exhibition at the New Tretyakov Gallery, with a display that exhibited several books and art catalogues, both from Russia and from elsewhere. A rich selection of original books, now part of the museum’s library, was hosted in the vitrines and shelves, attesting the interest and connection of Russian artists to the international scenario of avant-garde researches that had developed abroad.

The experience of the museums of pictorial culture can be retrospectively interpreted as a utopian dream that came true in a certain place and a certain era, and that permitted the development of an experimental platform over a number of years. However the utopian project ended up being institutionalised. Closed in 1922 due to lack of financial support in a harsh socio-political and historical environment, the Muscovite section was acquired in its totality by the Tretyakov Gallery, which, in 2019, finally brushed away the dust to allow a second look at this fascinating episode in art history.

- Zgur V. V., ed. The Museum for Painting Culture at Rozhdestvenka Street, 11 // Museums and Places of Interest in Moscow. Moscow: Moscow Municipal Economy Printing House, 1926. P. 82–85. In: Zhilyaev A., ed. Avant-Garde Museology, e-flux classics and V-A-C: New York, Moscow, 2015. P. 624.

- Tatlin V., Dymshits-Tolstaia S. Report on a Museum of Contemporary Art. 28 July 1918. URL: http://www.incorm.eu/documents.html#a1918.

- Malevich K. The Axis of Colour and Volume // Izobrazitelnoe iskusstvo [Plastic Arts], №1, Petrograd, 1919. URL: http://www.incorm.eu/documents.html#a1918.

- Ibid.

- Shterenberg D. The Museum of Artistic Culture // Report on the Activities of the Department of Plastic Arts of Narkompros, May 1919 // Izobrazitelnoe iskusstvo [Plastic Arts], №1, Petrograd, 1920. URL: http://www.incorm.eu/documents.html#b-1919.

- Kandinsky W. Khudozhestvennaia Zhizn [Artistic Life]. Moscow, 1920 // Kenneth C. L., Vergo P., eds., in Kandinsky.Complete Writings on Art, Vol. 1 (1901–1921), Editors (London: Faber and Faber, 1982, P. 437–444).

- Ibid.

- Rodchenko A. Declaration on Museum Management // Izobrazitelnoe iskusstvo [Plastic Arts], №1, Petrograd, 1920. URL: http://www.incorm.eu/documents.html#a1918.