expansion of gaze

In the digital environment, increasingly a subject of artistic inquiry, cinematic gaze is a key tool for shaping reality and the experiences of participants. Reporting on the constructed worlds of games, Daria Kalugina, author of the “Let’s Place” column on Haywire Magazine, discusses how the concept of the gaze expands within this emerging medium.

Gaze is a rich facet of games, one that functions differently in each fresh incorporation. It concerns the placement and movement of the camera of course, but also perspective in a more intimate sense.

A game camera might peer at a setting as a flat scrolling surface, might fly freely around a space, or peek over a player character’s shoulder. A gap between perspectives arises; what the player sees is not the same as what their character sees. This heightened view is essential for driving the action of a game, and bringing its environment to life.

And in that dynamic, a third perspective involves itself: that of the designer. The designer orchestrates a certain way of seeing, so that it can be interpreted by the player, and then performed by the character. This is the starting point for any game. Viewing is the player’s primary tool for understanding this world and how it works, and a game’s particular relations of gaze continue to inform its narrative and its mechanics of play.

In Beyond Eyes, these elements of gaze are arranged to visually represent the experience of a young blind girl named Rae. As she explores a whiteout expanse via sound and touch, objects come into view for the player to see. A fence, a cow. Rae and the player work together to assemble a rendering of the space she’s in—a kind of memory theater, into which all of the things unseen by Rae’s eyes have been projected.

This isn’t really so unlike more traditional walking simulators, like Dear Esther or Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture. Interaction is slight in these games, the player cast as an observer only. The story is buried within the landscape, becoming uncovered piece by piece as the player explores, changes their viewing angle. This too is memory theater, the narrative driven and held together wholly by gaze.

Augmented view

User Interface also mediates the player’s reading of an in-game world, often becoming entangled with the landscape, creating an augmented view. Sometimes this is purely utilitarian: plants to harvest, objects to pick up, and any other resources might be artificially outlined or otherwise highlighted out of friendliness to the player. In other cases, the augmentation is organically justified by the narrative. In Death Stranding, Sam has high-tech optics he can use to scan terrain and plot a route. This is just one example among many of a player character who can see things others can’t, by use of special abilities or fancy gadgets. Norman Jayden of Heavy Rain has smart sunglasses to aid him in his detective work, Aloy of Horizon Zero Dawn can find hidden things with an ancient visor she found.

Interface can sometimes overtake the landscape itself in terms of its importance to our moment-to-moment engagement with a game. Even in these cases, we’re still playing our role within a framework of gaze, albeit a highly mechanized one. The designer tells us not only what to see, but how to see it.

Delegated view

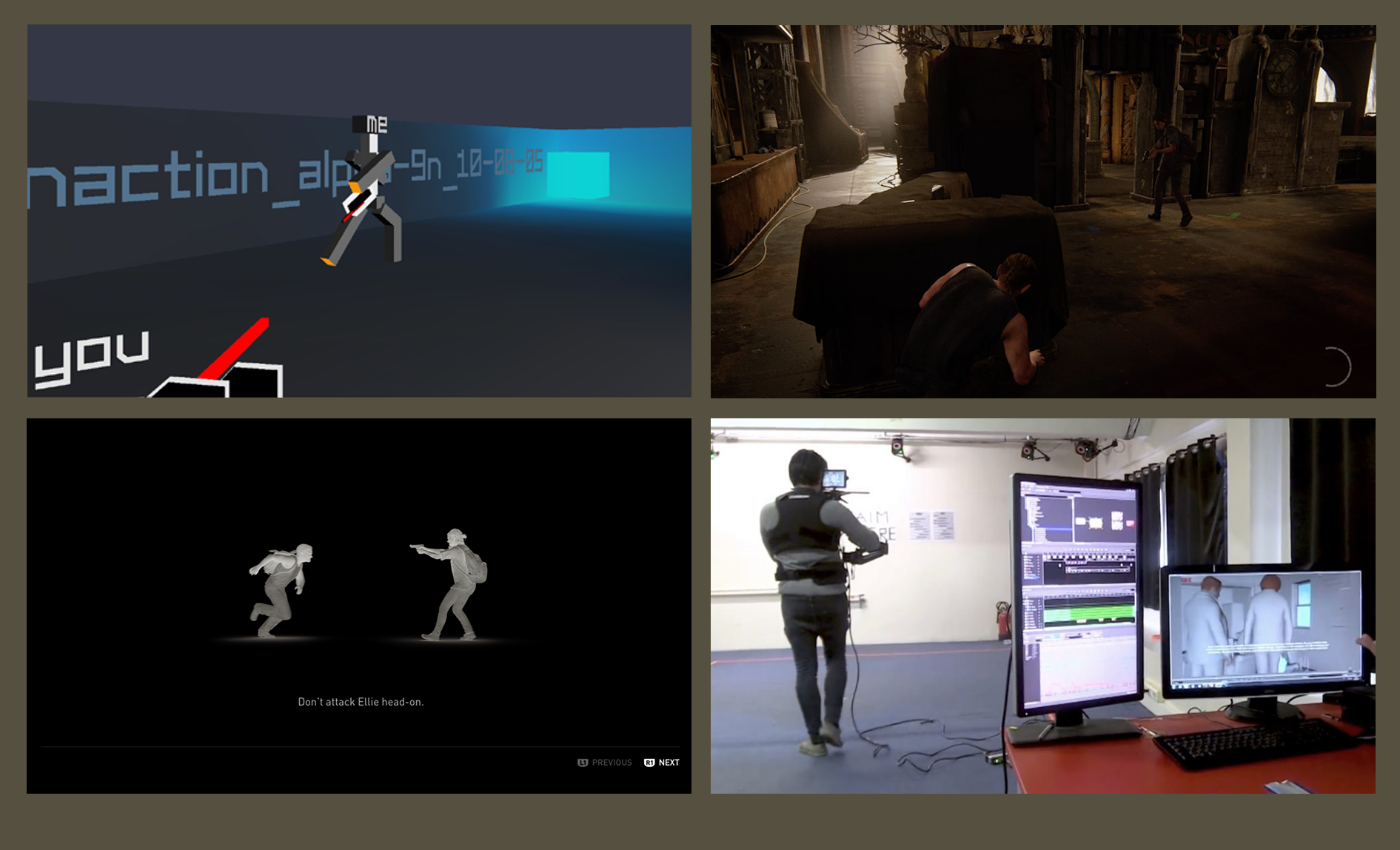

If we take a step back to look at the production side of creating game images, we notice another new relation: the delegation of gaze. On the physical set of Detroit: Become Human, a cameraman films an empty room. He records not a scene, but his own motions as an observer of a constructed event, by consulting a screen through which he can see the digital actors and space. His camera’s lens is turned inward, his motions delegated to the in-game cinematography. Motion capture technology records a set of vectors and coordinates not only for the actors on set, but also the camera itself. Both the cameraman and the actors are on the same level as they join our expanded set of viewers and viewed.

In his game 2nd Person-Missing-in-Action, Julian Oliver works with a similarly split view. We see a simple figure standing in front of us, and at first things look like any other first-person game. But in fact, the character we see in the frame is the protagonist, under our control, and the one whose point of view we see from is our enemy.

This introduces yet another aspect to our relations of viewing: this time the segmentation and sharing of gaze takes place not only between the production set and the game space, but also within the game world itself. The player sees themselves, and controls themselves, through the eyes of their enemy. It gives a new sense of agency to a non-player-character. At the same time, the rift between the player’s view and the character’s widens, thus highlighting the multivalence of delegated gaze even further.

(Spoilers f0r The Last Of Us Part II follow)

We play The Last of Us Part II as two heroines in conflict, Ellie and Abby, our perspective and control swapping between the two as the story progresses. In one episode, Abby chases Ellie through an abandoned theater. Among the disused props and costumes, we chase a character whose role we were playing just hours earlier. As we pursue Ellie we already know what tools are in her inventory, and we can anticipate her tactics.

This simple yet effective episode again demonstrates the way gaze refracts, and how it belongs equally to characters, actors, cameras. It’s not a solid entity, attributed solely to the viewer or the director, but a prism which creates a multifaceted reading of visuality.

Sometimes, that construction of vision is connected with movement: the captured movement of camerapersons and actors. This vision is alienated, reconstructed, and delegated.

Invisible landscape

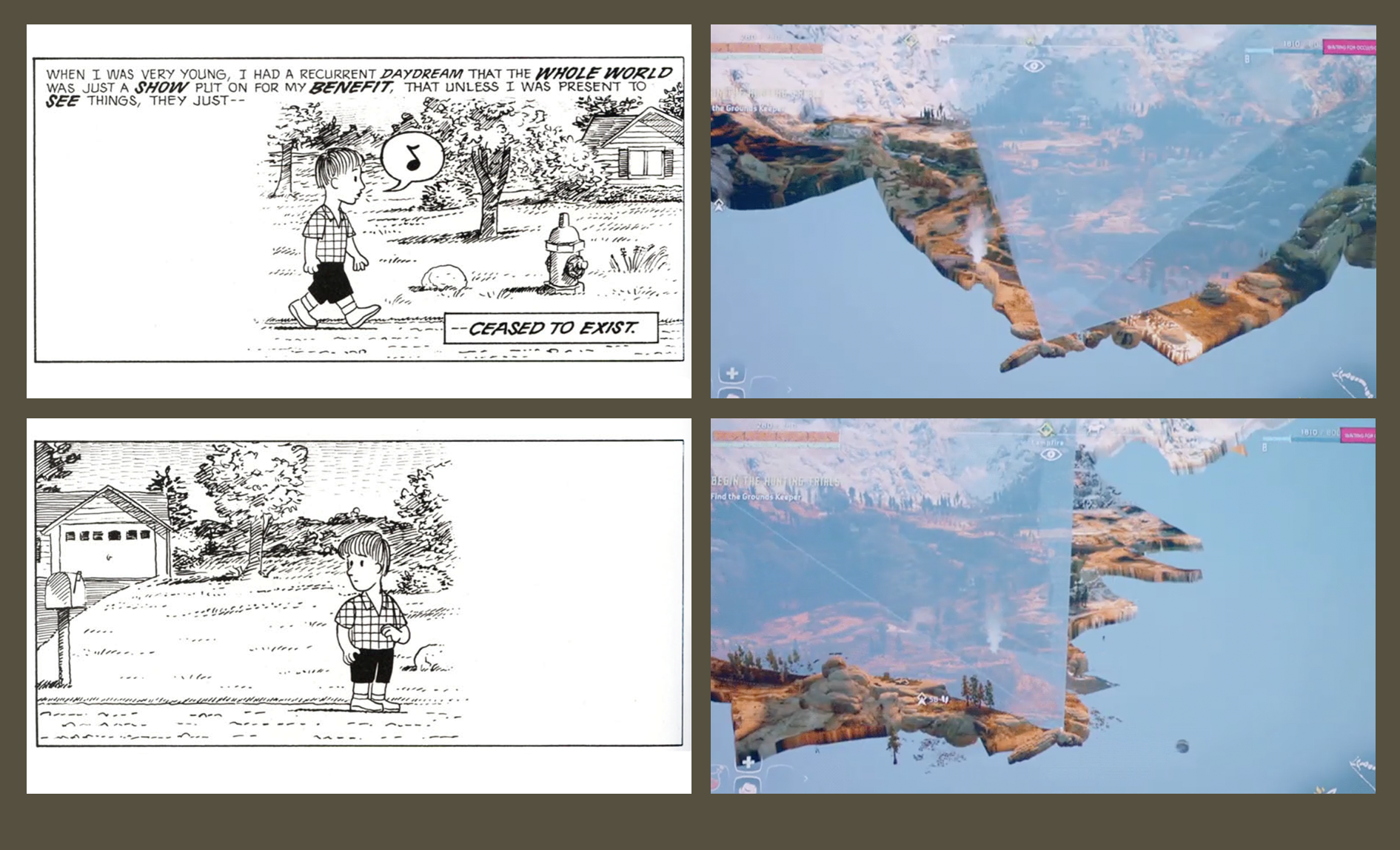

In order to portray realistic worlds while keeping hardware running smoothly, developers use a number of tricks [ 1 ] 1. Jason Schreier. Horizon Zero Dawn Uses All Sorts Of Clever Tricks To Look So Good // Kotaku, 17.04.2017. URL: https://kotaku.com/horizon-zero-dawn-uses-all-sorts-of-clever-tricks-to-lo-1794385026. . In these moments, the artificial and utilitarian nature of what we see becomes particularly apparent. Now gaze is not only a narrative tool we encounter in relation to the protagonists, but also an instrument of development, used in shaping the game world. In Horizon Zero Dawn, the only slice of world being rendered at any given moment is that which is currently framed by the player’s view. Whenever we look away from things, they cease to exist.

This technical aspect of Horizon Zero Dawn is similar to the way Beyond Eyes builds its visible world inside a white void. A game landscape can be understood as a dynamic decoration, an array of assets assembled into a fleeting tableau. It becomes tempting to escape this constructed sense of vision, to see beyond the theater and into the place where endless skybox reigns.

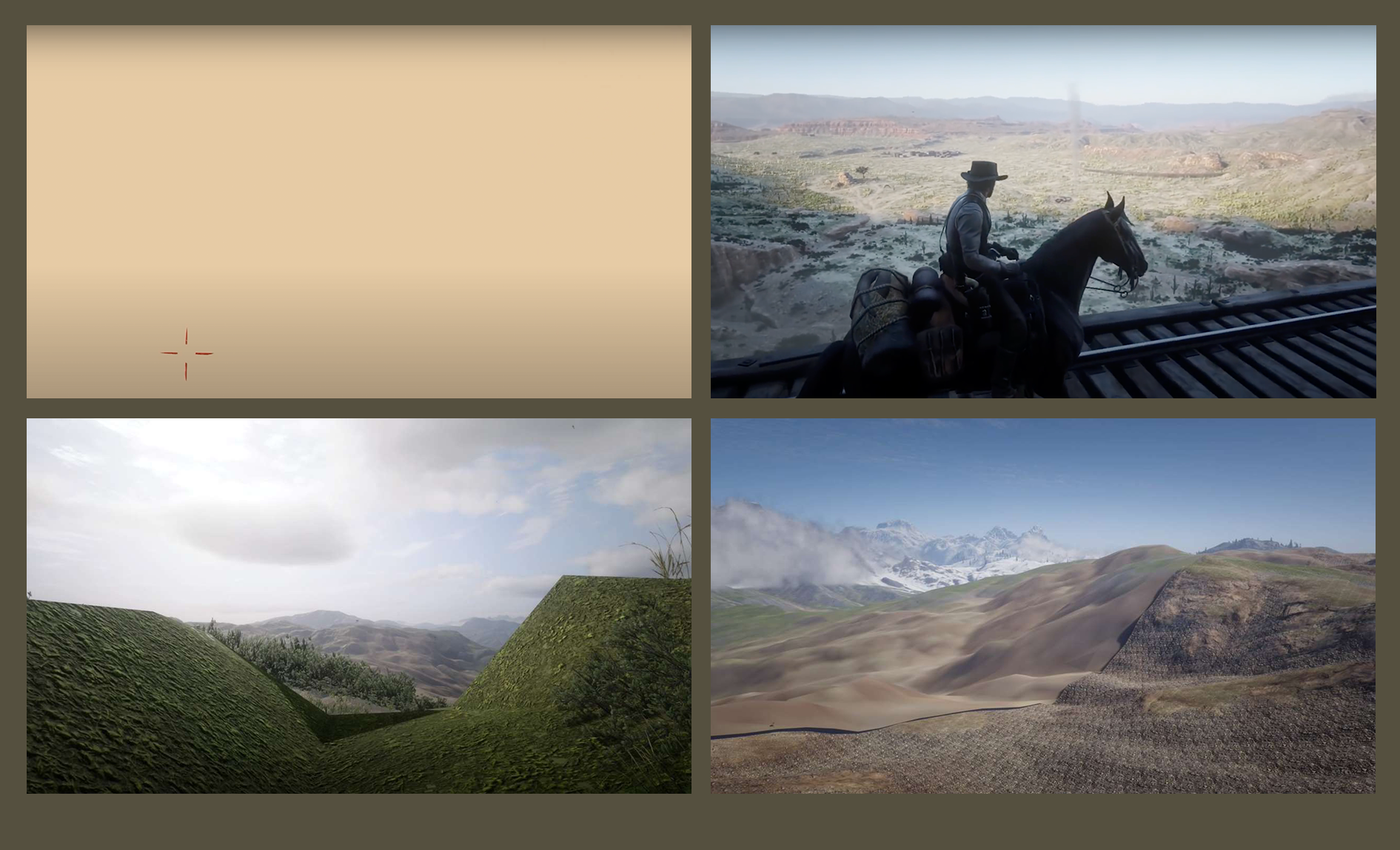

In a video essay, Jacob Geller discusses his discovery of a vast empty plain in Red Dead Redemption 2. There are no quests there, nothing moving, nothing happening. It seems strange that this lifeless territory would be a part of the game. And yet, surrounding this and every game environment, there is an even greater stillness.

Players can get there by slipping through the cracks in the structure and design of a game. Using bugs and vulnerabilities, it’s possible to take the character backstage, to wander around territory whose interactivity hasn’t been accounted for. Maybe a room only intended to be featured in a cinematic, or a vast world of background scenery normally kept out of reach.

A group of Australian developers known as The Grannies [ 2 ] 2. Luke Plunkett. Red Dead Online Players Escape Game World, Find Beautiful Desert Paradise // Kotaku, 25.06.2019. URL: https://kotaku.com/red-dead-online-players-escape-game-world-find-beautif-1835829191. have documented their travels out of bounds in Red Dead Redemption 2 Online. Breaking free of the developers’ constraints, their videos capture weird places, which nonetheless retain the illusive realism of RDR2, still composed of assets and decorations weighty with authentic heft thanks to the detail with which they were crafted.

This is the view out of time. However, speedrunners also make use of the cracks that lead to this timeless place, similarly thwarting the design and subverting the story. Even how we see the sky-world is bound up in our gaze: we may use it to get from point A to point B in the most efficient possible way, or we may go there to escape time altogether, to go adrift outside of the narrative.

Invisible labor

In Untitled Goose Game, there’s a shopkeeper who becomes locked inside their own store. They can be heard trying to escape, but if the game is played normally, their struggle can’t be seen. Despite this, the hidden scene is fully animated. How does our gaze account for this invisible labor?

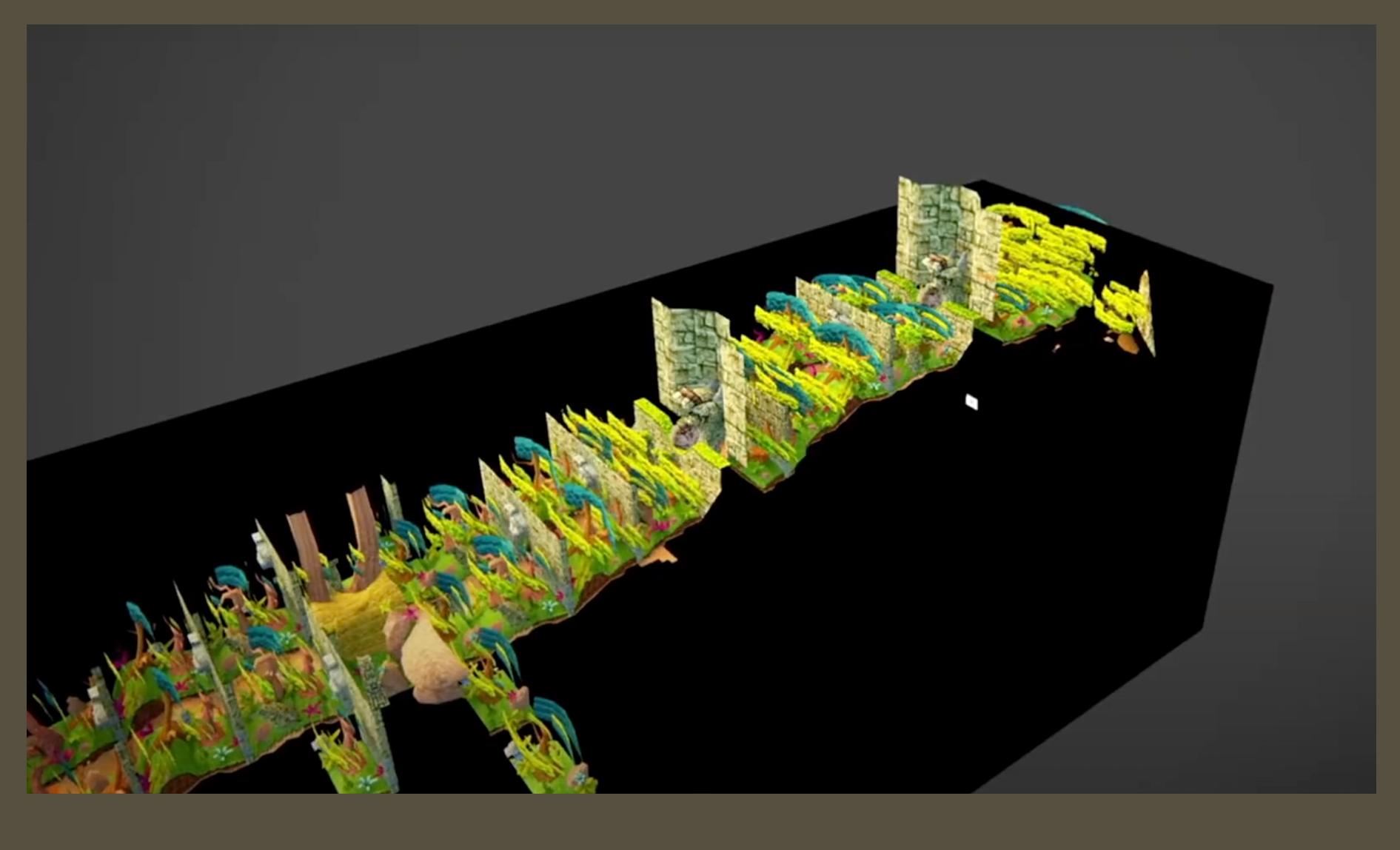

For Boundary Break, another document of out of bounds discoveries, YouTuber Shesez hacks into the code governing game cameras. A game’s camera is often somewhat under the player’s control, but still must respect the restrictions of the design and the virtual environment. Shesez’s camera goes wherever he likes, including outside the world, or even inside of objects. This grants an intimate look at the assets making up the terrain, and provides insights into how the illusion is maintained.

One of his videos is focused on The Last of Us, a good example of a game constructed as theatre. Not that memory theater of pure space and sight, as we see in walking simulators, but a vast production, millions of assets assembled into a timeline of scenes with actors, extras, costumes, and props.

With the hacked camera, it becomes possible to see the artifice, and the labor, behind this production. There are moments when characters load their truck with invisible suitcases. Actors pose like scarecrows until they receive their cue to perform. This theater is filled with objects and events of various degrees of conventionality. And since the limits of the illusion are only defined by the camera, which is always on the move, there is no strict border between what is inside and outside the scene. It’s a little like the scripted enemies in a stealth game: the computer controlling them always knows where the secret agent is, but the guards simply choose not to see him for as long as he remains in shadow.

Uncharted 4 offers similar backstage imagery to the eye of the hacked camera. In one scene the player might hear gunshots from somewhere nearby—these turn out to be emitted by fully rendered weapons floating in the air with nobody to pull the trigger. Even the trees reveal themselves to be flat textures, always turning to face the player in order to appear full.

An extreme example of this compounding stagecraft comes when Drake and Elena play the final level of Crash Bandicoot during a quiet moment in Uncharted 4. The player controls Drake controlling Crash, the characters commentating upon the action as it unfolds on a flatscreen TV in their living room, akin to play within a play. And yet, the two game worlds share a common plane. The cartoon world of Crash Bandicoot is hidden spatially beneath the realistic one of Uncharted, ready to make its appearance when called upon. They’re the same software running on the same hardware, underpinned by the same invisible labor. The game engine becomes an omniscient spectator, privy to every facet of the stagecraft. Simultaneously it’s an unseen actor, an invisible prop like a magical artifact, placed somewhere backstage to keep the world moving, ensuring the correct execution of the code.

Another side of this invisible labor is the simplification of actions when they take place off camera. Tess’s dramatic offscreen final stand in The Last of Us is handled just like one of those invisible suitcases—as soon as the door closes behind Ellie and Joel, Tess lies dead, even before the sound of the fight that kills her. Action is equated to its visibility, and when we can’t witness it, we can only trust the game. One could ask how detailed and autonomous a game world can be without a player to watch it.

Red Dead Redemption 2 makes an attempt to answer that question. Its realism and credibility are its defining features, with all the detail it affords things like the skinning of animals, the gradual decay of corpses on the side of the road. This world isn’t one that seems to immediately remodel itself depending upon where the player looks. It performs an illusion, at least, of autonomy: when the player sets something in motion, it appears to stay in motion.

But amidst all that spectacle, the invisible labor becomes overwhelmingly apparent as grueling, technical work. Red Dead Redemption 2 has become an infamous example of labor issues sadly common to projects of such scale in this industry, the crunch and unethical working conditions [ 3 ] 3. Jason Schreier. Inside Rockstar Games' Culture Of Crunch // Kotaku, 23.10.2018. URL: https://kotaku.com/inside-rockstar-games-culture-of-crunch-1829936466. , all staring us back in the face as we take in its spectacular landscapes.

***

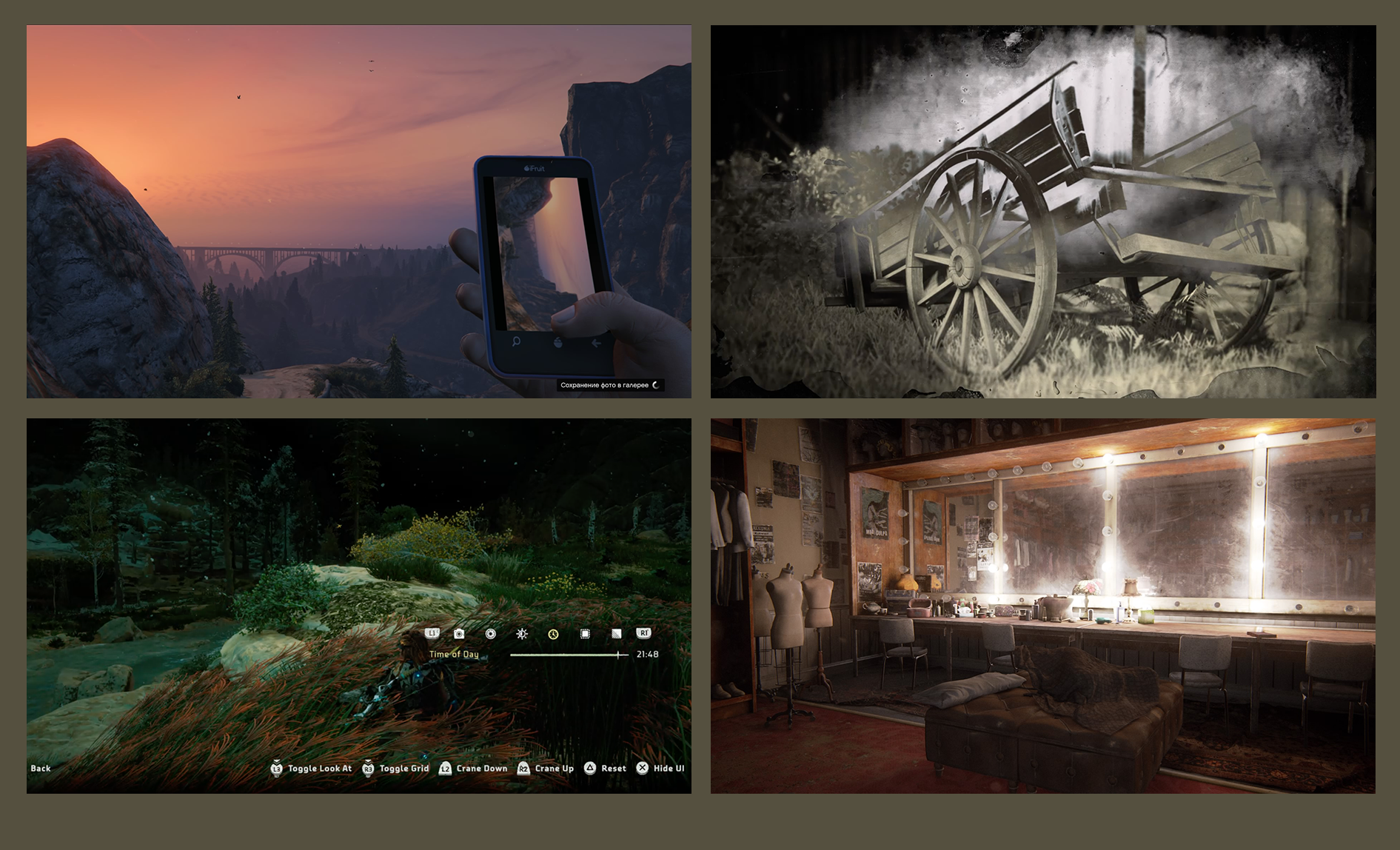

In-game photography stands alone among this multitude of in-game views. It functions as a superstructure of user interface, creating its own specific relations of gaze. There are at least two ways this mode can function. In one, the protagonist holds the camera in their own hands: a view of Grand Theft Auto V’s Los Santos captured with a phone, or a daguerreotype portrait in Red Dead Redemption 2. In these cases the photographic view is cast through the eyes of characters living within the game world, the player participating in their point of view.

Other times, what’s offered is a true photo mode, which isn’t connected to the character but directly with the player’s view. Photo mode breaks away from the direction of the designer, temporarily delegating freedom of view to the player—within certain constraints. This camera can float up or down and side to side, change its tilt or depth of field, even add special effects. It can modify the world too, make characters invisible or change the time of day. All to achieve the perfect picture. And this is a photographic camera, not a filmic one. Everything happening before its lens freezes, any battle, all dramatic tension suspended for the sake of timeless admiration. It is an authorized exit from the narrative, a denial of in-game death. In these frozen moments, like in memory theater, viewing becomes the only tool of communication with a game.

But this gaze goes both ways. While the player watches the game, the game watches them back, whether through the flat trees always facing us, or more literally, through the collection of personal data. Watch Dogs 2, a game that explores issues of privacy and digital media, is itself a tool of surveillance [ 4 ] 4. Will Partin. The Thousand Eyes of “Watch Dogs 2” // Los Angeles Review of Books, 19.02.2017. URL: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-thousand-eyes-of-watch-dogs-2/#. . Ubisoft’s license agreement lists all types of data the game will collect, including hardware specifications, internet provider, location, and plenty of statistical data on how we play, and for how long.

And so we see how a game spans a multitude of views, across multiple relations. Players watch the environment, the character actors are watched by motion capture sensors, online players watch each other, corporations watch their users—and the environment watches the player. The player becomes the object of this multifaceted viewing, standing in the spotlight of attention.

- Jason Schreier. Horizon Zero Dawn Uses All Sorts Of Clever Tricks To Look So Good // Kotaku, 17.04.2017. URL: https://kotaku.com/horizon-zero-dawn-uses-all-sorts-of-clever-tricks-to-lo-1794385026.

- Luke Plunkett. Red Dead Online Players Escape Game World, Find Beautiful Desert Paradise // Kotaku, 25.06.2019. URL: https://kotaku.com/red-dead-online-players-escape-game-world-find-beautif-1835829191.

- Jason Schreier. Inside Rockstar Games' Culture Of Crunch // Kotaku, 23.10.2018. URL: https://kotaku.com/inside-rockstar-games-culture-of-crunch-1829936466.

- Will Partin. The Thousand Eyes of “Watch Dogs 2” // Los Angeles Review of Books, 19.02.2017. URL: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-thousand-eyes-of-watch-dogs-2/#.