performing archives

This text attempts to unfold some ideas around two recent archive-based presentations at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art: Bik Van der Pol’s Far Too Many Stories to Fit into so Small a Box and Karol Radziszewski’s The Power of Secrets, marking 30 years of work at the CCA that have seen upheaval inside and outside the institution. The two presentations play aptly and equivocally with definitions between solo and group shows and, in their different ways, tackle the past, individual and collective memory and the politics of historical memory. They pose various questions, dealing with past works by other artists, archive materials, micro narratives and the degree to which an institution can cope with hosting “too many stories” on its premises.

“If a government has, and had, an agenda of changing everything, always, and as a long-term plan, to erase everything, then you need to archive. Urgently,” claims one of the voices in the mediation text of Far Too Many Stories to Fit into so Small a Box, designed as a visitors’ companion in a mobile speaker. The exhibition is not the first to show the CCA’s collection, but is arguably the only one to date that looks at the collection from different angles and provokes questions about its status, revealing the context of the institution’s early years and what it took to start a collection that is far from formalised. The show brings together not only the CCA’s collection and archival pieces, but also stories gathered in the course of preparations for the show. It uncovers selected pieces to show the multiplicity of solo and group shows by mid-career or lesser-known artists who have passed through the institution’s doors in the last three decades, leaving their traces and understatements. Indeed, the informal stories behind the objects and their often vague status play a key role in the exhibition narrative, which can be read as a fragmented, unfinished history of the institution as told by these objects and their voices. “We were interested in gossip and half-truths from our interlocutors, who speak of the same exhibitions, but whose memories of them are different,” curator Joanna Zielińska explains. [ 1 ] 1. All quotes are based on a conversation between Romuald Demidenko and Joanna Zielińska that took place on 21.12.2019. She had the idea of inviting the Rotterdam-based Dutch artist duo Bik Van der Pol back in 2015 and the CCA’s history and its collection was a crucial reference point, but it took much longer to pinpoint the most telling features of the collection. The methodology of the duo, Liesbeth Bik and Jos van der Pol, who spent three months as the CCA’s residents from March to May 2019, is to create, as they put it, “site-sensitive works”. What they have done, as we read in the press release, is to “critically examine the history of the CCA from the vantage point of outsiders”. The artists have previously worked in a similar vein with the collections of other art centres. They were behind Were It As If (2016) at the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam, marking the 25th anniversary of the Center’s operation, as well as Fly Me to The Moon (2006) at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, where the artists worked on the museum’s oldest object, a moon rock, and they also organised Married by Powers (2002), an exhibition encompassing works from FRAC Nord-Pas de Calais in Dunkerque that was presented at Tent, Rotterdam. According to Zielińska, their method of the Dutch duo, called “dynamic script”, is based on interviews, with subsequent modification of the gathered narratives. The final script is composed from more than 20 interviews transcribed 1:1.

Far Too Many Stories… speaks subjectively of the institution, to some extent constituted by a white square on the floor — a stage — in the central part of the exhibition, referring directly to Akademia Ruchu (Academy of Movement), an experimental theatre company set up in 1973 and run by Wojciech Krukowski, [ 2 ] 2. Also known as "Movement Academy". Akademia Ruchu. Miasto. Pole akcji = City. The Field of Action, ed. Małgorzata Borkowska (Warszawa: Stowarzyszenie Przyjaciół Akademii Ruchu, 2006). Some of the works are in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (Accessed 30 Dec 2019). the second director of the CCA. Artists were always present at the CCA, some working there and others temporarily residing. “Yes, of course, I was living in the Castle. Once on a Sunday morning, very early, I heard strange voices. I went to the window, and there was the Dalai Lama, standing in the yard”, Zbigniew Libera recalls. The time when Krukowski took up his post at the Ujazdowski Castle at the beginning of the 1990s coincided with the period of political transformation in Poland. One part of the show exposes the original red brick wall — a more authentic backdrop to events that occurred in the early years of the CCA, now hidden under the white wall of more recent times. Next to the red brick, windows have been covered with blue translucent foil as a reminder of David Hammons’ show Real Time from almost two decades ago — an empty space with a thin film of water on the floor, addressing references that include Derek Jarman’s 1993 film, Blue. “Everything was under construction, always in between. Always in movement, never stopping,” the first speaker’s voice continues.

The exhibition is being held at a special time, as a new director, appointed without a contest by the Polish Minister of Culture, takes up his duties at the CCA in early 2020. So the show captures the moment of another transition, attempting to document and speak of the institution’s fragile history, its missing parts, while what is yet to come is even more vague. One of the performers leading a performative guided tour quotes from Jenny Holzer’s Truisms (some of her best-known works, presented here in 1993): “The future is stupid,” “Men don’t protect you anymore”.

The central element in Radziszewski’s queer-archival exhibition, The Power of Secrets, is an open-space installation standing for the Queer Archives Institute, an autonomous nomadic para-institution, a show within a show that reflects Radziszewski’s distinctive methodology and a long-term project that collects objects and knowledge on queer narratives of Central and Eastern Europe.

Karol Radziszewski: This is a case study of the method. For example, this work, which is called Invisible [ 3 ] 3. Karol Radziszewski, Invisible (Belarusian Queer History), 2016, a series of five analogue photographs with handwritten notes in Belarusian. is of key importance for me, it is the quintessence of how I work. There is the oral history, the basis of the entire exhibition, the works, my interviews. It is an attempt to talk with the oldest people, who remember something, and at the same time a chance to find something that cannot be found in any other way, because it is not in books, it is not in any other materials. […]

Zofia Reznik: When did you consciously become an archivist?

KR: I think, fully consciously in 2009.

ZR: What happened then?

KR: Before, I was mainly interested in contemporaneity and facing up to what had been happening. I had been archiving everything, but I didn’t think about it in a systematic way. And in 2009 I started working on the “Before ’89” [4]http://redmuseum.church/demidenko-reznik-performing-archives#rec165323650 issue of DIK [DIK Fagazine], where I said that I would be collecting all these stories from the past of Eastern and Central Europe and somehow I started doing it, and I also went to talk with [Ryszard] Kisiel, [ 5 ] 5. Ryszard Kisiel, b. 1948 – one of the first gay activists in post-war Poland. Creator of Filo magazine, the second (after ETAP) Polish LGBT periodical, a monthly issued from 1986 to 2001 that contained news, reportage, prose, interviews, readers' texts, crosswords, tips, music charts, horoscopes, soft erotica, personal ads and an events calendar. See: "Ryszard Kisiel" in: Encyklopedia LGBT 26.04.2015; "Filo (miesięcznik)" in: pl.wikipedia.org 20.11.2019; "DIK and Kisieland at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw", dikfagazine.blogspot.com 2.05.2012. whose archive I saw for the first time. It was my first interview and the first view of his archive — it all gives the feeling that it just started then. The work on that issue of DIK lasted for more than two years, there was a lot of travelling. And in 2011, when it came out, I started working on Kisieland — a film about Kisiel, where we reenacted this [archivistic] part of his actions. [ 6 ] 6. Ryszard Kisiel created an underground archive of colour slides documenting private photographic sessions made at the turn of 1985/1986 in response to the infamous Operation Hyacinth (a clampdown on homosexuals by the Polish secret police). Karol Radziszewski, Kisieland, 2012, https://artmuseum.pl/en/kolekcja/praca/radziszewski-karol-kisieland. In the last decade the archive was always there in the background — closer or further, but always a basis for work. And this exhibition is built so that it is not a retrospective, but a selection of works. The archives are the main axis of it all. [ 7 ] 7. An interview with Karol Radziszewski by Zofia Reznik on 06.12.2019 at the CCA Ujazdowski Castle, Warsaw. With the participation of Radziszewski's friends, Bartosz Geller and Łukasz Wójcik. Audio recording in the archives of Zofia Reznik. Translation and all notes by Zofia Reznik, unless otherwise stated.

The exhibition includes a vast compilation of different artifacts, photographs and oral histories such as those focused on and collected around Ryszard Kisiel, a pioneer of gay culture based in Tricity (the three coastal cities of Gdansk, Gdynia and Sopot), active from the late 1980s who created Filo, one of the first communist-era gay zines. [ 8 ] 8. "Filo" might be read as a reference to the greek φίλος (phílos), meaning "dear" or "beloved", but also "a friend" or "a boyfriend", and "Filo" in Greek could be a masculine or neuter dual form, therefore signifying "two dears" or "two boyfriends"; see: "φίλος" in: en.wiktionary.org 23.08.2019.

KR: …this art and those objects, the visual aspect of it, is not insignificant — reading a book about it is not the same as seeing the scale of it, the physicality of those objects.

ZR: And in this sense, this materiality is an amazing carrier of the physical stimuli, that also effect the release of something from our bodies.

KR: You know … I know that people are aware that these clothes that lie here under the glass are theatrical costumes or museum objects, but when Ryszard [Kisiel] brought them to me from Gdańsk in a plastic bag… and they had never been washed, and you smell the smell, and touch those laces, and we laugh, and he crams it in that plastic bag… You know, it is very physical, also the smell, some of these people are dead or it was a model… I have never thought before that the smell of the 80s is preserved in it. It is strange, the sweat, but it is just so physical.

ZR: It’s a shame one can’t feel it here…

KR: You know, there are the bras that Kisiel’s boyfriend was wearing and they just, well, they stink… but this is just the magic of the body.

ZR: And you took it away from the viewers! And you could have given [laughs].

KR: Well, but I let them peep under the glass…

Next to Kisiel’s showcases with playful lingerie and accessories used in his photoshoots, there is a red cubicle with a micro exhibition Hommage à WS dedicated to Wojciech Skrodzki (1935−2016), art critic, writer and queer activist, co-curated with Wojciech Szymański, an art historian and curator who Radziszewski works with. [ 9 ] 9. Karol Radziszewski and Wojciech Szymański curated the monographic show Cruising dedicated to Ryszard Kisiel's archives, Gdańsk City Gallery, 2018. The environment-like section (and in fact reenactment of a show from the past) brings together works by artists who were part of an undocumented show that Skrodzki put together and that included autobiographical and erotic threads.

KR: … the idea is to show it as part of the method of work with archives, so you can only enter through the Queer Archive Institute. [ 10 ] 10. Queer Archives Institute was founded by Karol Radziszewski in November 2015 as an independent organisation, "dedicated to research, collection, digitalisation, presentation, exhibition, analysis and artistic interpretation of queer archives, with special focus on Central and Eastern Europe". See: http://queerarchivesinstitute.org. The presentation of QAI was the core part of Radziszewski's exhibition. A year later, in 2016, a similar archival project entitled "And LGBT culture won't wait!" ("A kultura LGBT nie poczeka!") was started by a lesbian duo, Agnieszka Małgowska and Monika Rak, who are virtually archiving the cultural activities of the Polish LGBTQ+ scene, see: http://akulturalgbtq.pl. The idea is also to show how you can queer the past without necessarily saying: he was a fagot, she was a dyke, but instead by looking at the existing things in a queer way. That applies to Wojtek Skrodzki, a well-known critic from the times of the Polish People’s Republic, a zealous Catholic who outed himself at the age of 80 and became an activist of sorts. We met at that time, but he died when I was in Brazil, so didn’t have enough time to develop it. But he left me the typescript of his biography, a childhood photo and various premises, that… I treat it as a sort of a fulfilment of his will [sighs embarrassedly] — in 1978 he made an exhibition that was supposed to be his coming out, which he called an erotic exhibition. [ 11 ] 11. Wojciech Skrodzki presents the exhibition Hommage to Andrzej Matynia (Wojciech Skrodzki przedstawia wystawę "Hommage Andrzejowi Matyni"), 1978/1979, The Critics Gallery (Galeria Krytyków), Warszawa. And from those texts and letters to friends, from his biographical notes, it is clear that he wanted to make an exhibition that in a way would reveal that he was gay, but at the same time would hide it, so that one wouldn’t guess. That’s why he openly writes… that’s why the undressed Natalia [LL], so that there was this feminine sexuality… [ 12 ] 12. Natalia LL, Natalia Lach-Lachowicz, b, 1937 – Polish visual artist based in Wrocław, known for photographic works, films, performances and texts on art, co-founder of the PERMAFO gallery, often associated with feminism. Her most well-known works include Intimate Photography (1971), Consumer Art (from 1972) and Post-consumer Art (1975). See: Krzysztof Jurecki, "Natalia LL", translated by Sylwia Wojda, culture.pl 2011. Her photos depicting naked female body were part of Skrodzki's original and reenacted exhibition. But there were also some minor clues that he planned on showing, photos documenting The Dead Class of Tadeusz Kantor. [ 13 ] 13. The Dead Class (1975) is the best-known work of the Polish artist and performer, Tadeusz Kantor (1915-1990). It was premiered at the Krzysztofory Gallery in Kraków, performed in many countries around the world and widely acclaimed by critics. It tells the story of elderly men who revisit their past and confront the impossibility of returning to one's childhood and also of the outbreak of World War II. See: Karolina Czerska, "The Dead Class – Tadeusz Kantor", transl. M.K., culture.pl 2014; Tadeusz Kantor, The Dead Class, 1976, https://artmuseum.pl/en/filmoteka/praca/kantor-tadeusz-umarla-klasa. So I was reading it and thinking “Fuck, Kantor. What is this about?”. But then I started to look for photos and it turned out that there was this one photo that was removed by the censorship — there in the catalogue, where there is an empty place. So we got to the photographer who made it and he gave us those photos for the exhibition. And suddenly it turns out that you can even show Kantor in such a way… that when you are gay in the 70s and trying to queer your reality, you can sample it from anywhere…

ZR: Even Kantor…

KR: …even Kantor.

The carmine room with a few circular holes in its temporary walls is designed as a reference to intimate club rooms that provide safe anonymity for sexual intercourse, but it might as well resemble a womb or a photographic darkroom used by professional and amateur photographers in the 70s and 80s. The room was an extension of the exhibition site, a reaching-out architectural hub, enabling the two shows (Far Too Many Stories… and The Power of Secrets) to symbolically meet via the glory holes carved out from the institution’s walls, as one of Radziszewski’s friends brilliantly pointed out during an informal guided tour. [ 14 ] 14. A remark of Łukasz Wójcik.

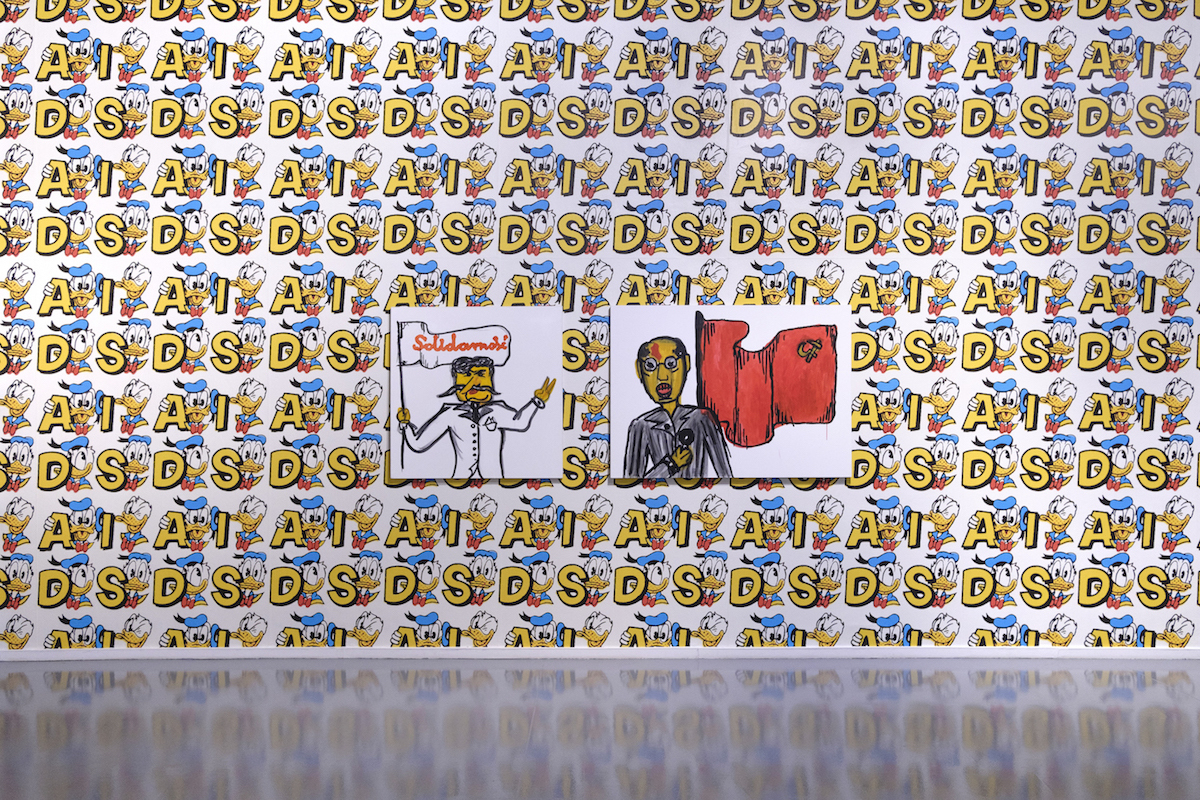

KR: There is a focus here on appropriation art, also as a method of producing, expanding the materiality of art history and history in general. So this picture is called Hyacinth and it is apparently the first-ever visual representation of Operation Hyacinth. [ 15 ] 15. Operation Hyacinth (1985–1987) was a large-scale operation by the Polish secret police to gather information on Polish homosexuals and their circle. About 11,000 people were registered, files were opened on them and many persons were arrested (those arrested had special files opened and often had to sign a statement). The operation drove members of the gay community underground. See: "Operation Hyacinth", in: Wikipedia.org 03.01.2020. And it is my typical method… let me decode it: I wonder about the most easy-going, best artist of the time, who might try to portray it […]. So, it’s Operation Hyacinth and it’s 1985 and what are the hottest aesthetics of the time? The new expressionism, Neue Wilde — the expression of German painters. [ 16 ] 16. Neue Wilde, Junge Wilde – a painting style that grew in popularity mainly in Germany at the end of 1970s and had its heyday in the first half of the next decade. It was linked to the Italian Transavantgarde, American neo-expressionism and French Figuration Libre. See: "Neue Wilde", in: de.wikipedia.org 27.08.2019. So from those painters I choose A. R. Penck, who is a bit less known than [Georg] Baselitz and [Jörg] Immendorf, [ 17 ] 17. A. R. Penck (Ralf Winkler, 1939–2017) – German visual artist born in Dresden; Georg Baselitz (b. 1938) – German painter and sculptor; Jörg Immendorf (1945–2007) – German visual artist and scholar. but his style is more brutal, it evokes cave drawings, very primitivistic — it reminds me of Keith Haring. [ 18 ] 18. Keith Haring (1958–1990) – American artist known for using pop art and graffiti-like aesthetics and for addressing homosexuality and AIDS. But he is American, so we need to postpone that tradition, because I’m looking more locally. And it turns out that there are drawings of Ryszard Kisiel from the Filo zine, that are simply about HIV and AIDS, showing various safe and dangerous sexual positions, and that these drawing schemes are totally part of this aesthetics. So I take West — the first painting that A. R. Penck made after escaping from East to West Berlin, which is in the Tate collection, so it is well-known and can be referred to. [ 19 ] 19. A. R. Penck, West, 1980, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/penck-west-t03303. The characters on the left and right are partly copied […] So this is where “AIDS” appears, he also codes letters — “A. R. Penck”, and here I put “UB” [Urząd Bezpieczeństwa — Department of Security], [ 20 ] 20. The Ministry of Public Security or Department of Security ("Urząd Bezpieczeństwa") was the Polish secret police and intelligence service from 1945 to 1954. In 1956 the Department of Security was renamed the Security Service ("Służba Bezpieczeństwa") and continued to operate until 1989. See: "Ministry of Public Security (Poland)" in: wikipedia.org 06.01.2020; "Służba Bezpieczeństwa", in: wikipedia.org 13.12.2019. at two characters holding each other’s hands, I create a policeman wearing a hat, I insert the drawings of Kisiel and I imitate the whole in scale. […] The result has to be such that, when an art historian enters, they say: “Oh, this is A. R. Penck!'”. I had some French curators here three days ago and they said: “Oh, A. R. Penck!”. […]

And this Operation Hyacinth, that everyone speaks about so mythologically, no one really knows what… but then — OK, now we have the images that show how it was. So now we can start the conversation: if it was like that or not, or some other way. But it is a starting point for an average person who might have heard of Operation Hyacinth for the first time in their life — they will see this picture and will wonder: here’s a policeman, there is sex — what was going on? — pink folders, something here…

ZR: So again, materiality as a place of entry.

KR: Yes, because it is crucial for this exhibition to create a kind of material culture based on stories and archives, so the archives are performed by giving them a body or the bodies of those who speak, or bodies in the form of works of art that are physical and material. They are sculptures, images that one is not only projecting or inducing, but you face them. You have to go around this sculpture [Mushroom], for example, and you already know the scale of this toilet [ 21 ] 21. Karol Radziszewski, Mushroom (Grzybek), 2019, steel sculpture. Radziszewski's sculpture is a reference to one of popular cruising spots – a public toilet (no longer existent), shaped like a mushroom, standing on Three Crosses Square in Warsaw. The work mimics the style of the famous Polish sculptor Monika Sosnowska (b. 1972), who often addresses issues of socio-political change as manifested in architecture. The crushed and distorted form of the sculpture refers to its demolition. and it starts working, stimulating your imagination.

“Archives must be reenacted, especially as QAI always works on different terms, depending on where it is being shown,” Michał Grzegorzek, the curator of Karol Radziszewski’s show, explains. In that sense, the artist brings back and reenacts different, and very often personal narratives, to build up the image of a collective queer body. Its history — rather like the history of an institution — is fragmented and hard to describe or show, and always subjective. One of the show’s protagonists is Ryszard Kisiel, who is the protagonist of an ongoing project started by the artist in 2009, with the 2012 documentary Kisieland — overlooked in the collective memory.

KR: This, for example, is a sculpture that pretends to be a work by Monika Sosnowska. But it is about the Mushroom, that picket [slang for a gay meeting place], and poses common questions about what is possible. What queer form of commemoration can function and what is worthy of being a sculpture — could the most famous gay toilet be worthy?

The queer body is under threat from resurgent homophobia in today’s Poland (one of the biggest countries in the EU). To mention one emblematic manifestation of homophobia, in July 2019 participants of the first rainbow march in the city of Białystok (Radziszewski’s hometown) were met with rage and violence (the words of The New York Times) as homophobic insults were hurled at them by right-wing advocates. [ 22 ] 22. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/27/world/europe/gay-pride-march-poland-violence.html (accessed 30 Dec 2019).

Both exhibitions continue the archival line practiced by different art institutions reflecting on their past recent years, such as Working Title: Archive at Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź presented in 2009, which revived the memory of the museum’s most remarkable shows and marked the launch of its second site. As the written guide to the Łódź show stated: “Today’s culture is constantly in archive mode — documenting and attempting to preserve every aspect of the reality that surrounds us”. [ 23 ] 23. Working Title: Archive, Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, Poland, 27 February – 3 May 2009, curated by Magdalena Ziółkowska, with work and texts by authors including Marysia Lewandowska and Lasse Schmidt Hansen; See: Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Innovative Forms of Archives, Part One: Exhibitions, Events, Books, Museums, and Lia Perjovschi's Contemporary Art Archive, e-flux Journal #13 - February 2010 (Accessed 30 Dec 2019). On a wall at Too Many Stories… we see a poster of the exhibition by Neil Cummings and Marysia Lewandowska, Enthusiasts (2004), the first iteration of their long-run “extensive research amongst the remnants of amateur film clubs in Poland under socialism”, recently acquired and featured online by Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. [ 24 ] 24. Enthusiasts: archive. A project by Neil Cummings and Marysia Lewandowska, launched in October 2019, www.entuzjasci.artmuseum.pl/en/about/ (Accessed 30 Dec 2019). In that sense, art institutions become libraries, gathering and preserving various traces of the past, and activating them whenever needed. Missing links in the CCA’s timeline can serve as fertile ground for its future programming — disseminating knowledge and using mediation tools to highlight what has been overlooked and sometimes to repeat what is already known. In the final room we see eight TV screens collecting documentations from the backstage of exhibitions, revealing how quickly they were assembled. “The Centre is a field of action, it attracts attention” the subtitles read. The opening of Marina Abramović’s show is blended with a press conference with Annie Leibovitz, interviews or artist talks, excerpts from workshops, documentations of performances and the Animal Pyramid by Katarzyna Kozyra from 1993, which is one of the most emblematic works of Polish critical art. Publications by CCA are laid out on tables with posters from shows above them: Tony Oursler (1999), Jenny Holzer’s Street Art (1993), Nedko Solakov (2000), Devil’s Playground by Nan Goldin (2003). Curators reveal that Devil’s Playground “is a show that Karol Radziszewski mentions as having helped him to come out”.

queer archives in “the power of secrets” and the cca’s collection, with its backroom micro histories, complement each other, in the sense that informal narratives often push the boundaries of what is called official.

ZR: I would like to ask more about the archival impulse. What’s behind this need to deal with archives, what motivated you to start doing it?

KR: I have said it many times — it is important for me that it is about identity, or at least the first impulse was about identity. When I did the first openly homosexual exhibition in Polish history it was 2005 [ 25 ] 25. Karol Radziszewski, Faggots (Pedały), 2005, private apartment, Warsaw. See: Joanna Sokołowska, "Pedały Karola Radziszewskiego", Obieg 24.06.2005. and I had seen things by Paweł Leszkowicz’s, [ 26 ] 26. Paweł Leszkowicz (b. 1970) – Polish art historian and scholar, curator of the exhibition Ars Homo Erotica (2010) at the National Museum in Warsaw. some faint traces of the past. And when I officially came out and saw people’s reaction — that of my mother and of my environment — I realised that there are zero reference points. And there’s nothing in history or in Polish art to lean on as an artist, to refer to, even to see yourself in. So then I understood that the lack of voices and the absence of these themes in the public sphere is a form of repression. […] And this exhibition is the quintessence of it — it is a political work intended to build the visibility of this history that existed, but that had to be discovered and conveyed in a form that made it readable for people. Because all these things existed, functioned somewhere — these historical figures, figures from Poczet [ 27 ] 27. Karol Radziszewski, Fellowship (Poczet), 2017, series of 22 paintings showing non-heteronormative people from the history of Poland. It is also a reference to Jan Matejko's famous series of drawings Gallery of Polish Kings, 1890–1892. See: https://artmuseum.pl/pl/kolekcja/praca/radziszewski-karol-poczet. or archival figures, — so what I’ve started to do is meant to enable others to find out, like I have found out.

Considering the two exhibitions only through the archivalist point of view would not do full justice to the curators’ interest and the dimension of the exhibitions. “The CCA’s tradition of exhibition-making in an almost spontaneous manner derives from theatre rather than from the visual arts”. Bik Van der Pol’s curator and writer Joanna Zielińska is known for her cutting-edge curatorial proposals, often connected with time-based arts, such as her recent projects at the CCA: Performance TV co-curated with Michał Grzegorzek and Agnieszka Sosnowska (2017−2020), Objects Do Things (2016) or Nothing Twice at Cricoteka in Kraków (2014), and The Book Lovers, exploring written work by visual artists alongside David Maroto (ongoing from 2011). [ 28 ] 28. See: The Book Lovers, ed. David Maroto and Joanna Zielińska, Sternberg Press, 2015. Zielińska previously worked as artistic director at Znaki Czasu Centre of Contemporary Art (CoCA) in Toruń, Poland, where she curated the inaugural exhibition and the institution’s programme (2008−2010). Reenactments as part of Far Too Many Stories… are by a group of artists and amateurs from different backgrounds and origins, including storyteller Agnieszka Ayen Kaim, singer Mamadou Góo Bâ and choreographer Ania Nowak helped by Jagoda Szymkiewicz. All of them were given the final script to interpret so that they could choose parts of it and select objects to focus on. Billy Morgan leads an intriguing tour around selected works in the exhibition, asking the audience to repeat gestures or sentences after him while confessing personal stories: “Yesterday I presented my performance in the sculpture park at Królikarnia and a man I don’t know yelled ‘pedał’ [eng. faggot]. It was a reminder that public space is not a utopian free-for-all, it is a deeply insecure, heterosexist topography governed by its own set of norms”. The touching works tackling body issues are particularly noteworthy and resonate with performances complementing the exhibition such as Family of the Future by Oleg Kulik (1999), “a visualisation of all living creatures living happily together”, as the wall-text tells us, Barbara Kruger’s Your Body Is a Battleground (1989) originally created for the 1989 women’s rights demonstrations in Washington DC and shown in Warsaw in 1995 (resonating with passage in the Polish Parliament of legislation allowing abortion in certain instances), or Nan One Month after Being Battered by Nan Goldin (1984), “I took that picture so that I would never go back to him,” says Goldin about the man who attacked her. In this way the exhibition documents the bodies of the artist and not only institutional archives. Far Too Many Stories… shows objects and artifacts, activates stories through performances and includes a selection of videos documenting such works as Other Dances (one of the most emblematic spectacles of Akademia Ruchu), performances by Antoni Mikołajczyk, a film on Andrzej Dłużniewski blended with a public talk by Barbara Kruger, an interview with Nan Goldin or excerpts of an exhibition by Yoko Ono. In the next room there is a collection of posters and publications that accompanied the shows. Far Too Many Stories… also offers another significant mediation tool: the Other Lessons programme, focused on Akademia Ruchu, aims “to merge the past with the present”, Zielińska says. It includes workshops with artists such as Alex Baczyński, who uses some of AR’s performances as references, and with Jolanta Krukowska, a performer, who worked in the collective for nearly three decades with her life partner Wojciech Krukowski. A range of guided tours sheds light on the complex nature of CCA’s collection, including tours led by curators who have worked here for many years and a conservator who discusses works that were hard to deal with due to the unusual materials from which they were made. Marek Kijewski’s black-red bust on a plinth, Fred Flintstone of Knossos (1997), covered with a specific type of Haribo jelly beans is a case in point: disintegrating parts of the work were hard to replace with new ones due to declining popularity of the confectionery. Works with collective authorship such as a painterly installation by Winter Holiday Camp also pose difficulties: how can a work that was created by a people now in different locations be maintained? The problem is also relevant for collections and archives in a broader sense: how do we make sure we care for them properly? And what happens to objects with non-obvious status?

KR: I have very unique things that people donate to me privately, for example the costumes that Ryszard Kisiel used for photo sessions and photos that I developed myself (the originals are slides, 300 of them) in one suitcase. Ryszard thought that they had burned in my studio, [ 29 ] 29. Radziszewski's studio and the studios of other artists were damaged in a fire in 2013. See: Zuzanna Janin, "Dzieła sztuki współczesnej i pracownie artystów zniknęły w pożarze kamienicy w Warszawie", natemat.pl 30.01.2013. but they were squeezed in between the clothes. […] This is a queer strategy of moving it [the archive], not having your own headquarters, and on the other hand, using the institution as much as possible to digitise, scan, correct, do conservation, insure it. […] I think I have to set up a foundation, because people don’t realise how much money is needed to digitise a large amount of materials, to keep them in good condition and to work with it at all. […] For example, one could say of my film Afterimages, [ 30 ] 30. Karol Radziszewski, Afterimages, 2018, film, 15'. See: https://archiwum2019.mdag.pl/16/en/warszawa/movie/Powidoki; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZOK8HgMgr6g. which is exclusively about one of Kisiel’s photographic films: “He just scanned it and recorded sound”. But scanning this one film, without touching it, so that it didn’t disintegrate, cost 900 zloty (each frame can be enlarged to the size of a billboard). And Ryszard has three hundred of these negatives.

ZR: And somewhere, at some point you have to choose something more valuable and sacrifice something else, right?

KR: Yes, but I also work in batches. We are also coming back to what is, maybe, an interesting topic… a bit of selfishness: you get something special and the question is how quickly you share it. Because everyone expects it immediately. If you make a discovery — you have knowledge, you take a journey, pay for the trip, convince someone, have a conversation, understand what it is, scan it, — people think that you immediately put it on the Internet and it is going to be everyone’s property, preferably in high resolution. Most people have this attitude — activists, scholars. And I think that ultimately such a democratisation of access is great — I would, of course, want a huge website with everything. But if something is part of the work, one of the stages, then I have to decide what I will take care of now, and what to hold back until I know what it is all about.

ZR: But I also sensed — correct me, if I’m wrong — a moment of suspension in this process, finding pleasure in having something just for yourself.

KR: It’s just exciting. But we’re now also talking about sources, from which I create works. When I work on residences and show the effects — like in Belarus or in Romania — that’s usually one work. (…) This exhibition shows a lot of such effects, fruits, transformations. I sometimes need to hold something for myself, enjoy it, or have exclusive use of it, so that I can then create a work that will be able to act as something more, something new.

What is perhaps more remarkable in the context of both exhibitions is the collaborative dimension of the project and the blurred borders between the exhibition format and the accompanying programme. Quite different for both: Bik Van der Pol’s presentation of their research project encompasses works conceived for the institution by many artists or left on site almost involuntarily. “Works were made for the space. And artists donated works (…) No contract, so a lot is unclear,” as the second speaker’s voice puts it. For Karol Radziszewski it flows from his practice of mapping queer microhistories almost from the beginning, restoring the memory of overlooked bodies and quotes from stories, “for the very first time with full awareness”, as he puts it, looking back at his queer childhood.

KR: Take this Donald Duck — quite late, just before the exhibition, I found a drawing that I had done, and it is from exactly the same year as the collage by Ryszard Kisiel with the AIDS Donalds that inspired me to make this wallpaper. So when I recalled this sticker, which I put on a pencil case or backpack as a child, it suddenly turned out that this Donald Duck was also present in this form [points to his mural] — there is a sailor, a tattoo with a heart… And of course it was not conscious, but now, as I look at it through everything that I know about queer things, it can be decoded in many ways. The basic interpretation would be that my imagination, that of a 9-year-old boy in Białystok, and the imagination of Ryszard Kisiel in Gdansk, who was sticking it in the first gay zine, met somewhere. For me it is also a matter of queer time, queer memory — cross-generational, connecting memory.

Shortly after the opening of the two exhibitions, CCA announced Michał Borczuch’s performative installation Untitled (Together Again), activated live on three different occasions, which looks back at “the past intertwinement of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and political changes, especially the political transformation in Poland”, framed alongside two shows as Performing Archives.

Queer archives in The Power of Secrets and the CCA’s collection, with its backroom micro histories, complement each other, in the sense that informal narratives often push the boundaries of what is called official, bringing a new understanding of how the institutional context can serve both for its own sake and for art practice, both as a consequence of an artist’s own endeavours and a vivisection initiated through someone else’s objective or a shared objective.

Both of the exhibitions and the current context in which they appear — a change in the management of the CCA — send us back to the 1990s, the “heroic years” of an institution in the making and the pre-teen years of Radziszewski, whose protagonists such as Ryszard Kisiel were active at the time and would appear afterwards in his Queer Archives Institute. A large part of Ryszard Kisiel’s archival matter appears — accessories from photo sessions displayed in the showcases or copies of spreads from his magazine Filo, alongside covers of other magazines such as Inaczej (Polish for “Differently”) or Okay.

A crucial part of Radziszewski’s practice is the enlivening of under-represented and significant figures and concepts of queer identity. Looking at the current practices of institutions that include a queer retro-perspective in their programme (Van Abbe Museum’s long-term project Queering the Collection with reading groups, guided tours and other activities addressed to overlooked queer communities, or the major recent Keith Haring retrospective at BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels), we could imagine that the CCA is considering a similar direction. And blockbuster institutional shows in recent years representing women artists show how contemporary art institutions are working to restore forgotten protagonists and rediscover important culture-forming characters that have been pushed to the margins in the past. It is clear that works by Karol Radziszewki and Bik Van der Pol’s proposal work very well in the institutional context. DIK Fagazine, a quarterly founded in 2005 which used to be Radziszewski’s trademark, with an uncanny logo by Monika Zawadzki of two penises facing each, has been showcased at the CCA several times, and Radziszewski already had a solo show there, I Always Wanted, back in 2007. This year’s event gives full rein to his almost obsessive way of working through the archives. It is the first such complete archival presentation in Poland, and has already been shown at Videobrasil (São Paulo, Brazil), Ў Gallery of Contemporary Art (Minsk, Belarus), Fundación Gilberto Alzate Avendaño (Bogota, Colombia) and Schwules Museum (Berlin, Germany), to name but a few venues.

Do the exhibitions tell us something about unknown archives or is it rather that the archives tell us about protagonists from the margins of the art world’s interest? In the opening part of Bik Van der Pol’s show we see a pile of stones which were a component of the installation Stone Circle by Richard Long (1977). The installation remained in the Castle’s deposit, but lost its certificate of authenticity and reverted to a material artifact. “This piece… it is such a shame it is covered with paint,” as we read in a line of a “dynamic script” describing Lawrence Weiner’s Far Too Many Things to Fit Into So Small a Box. The artist and the curator agreed in 1996 that the work would remain during the renovation works planned for the following year. The renovation did not happen, and the work became an informal CCA trademark until its removal a few years ago. The work now serves as the title of the show and its leitmotif of the show. Bik Van der Pol explains: “We live in very strange and radical times. If we think about climate change, maybe it would be best to get as high up as possible, to save yourself from the worst. The coastlines of Great Britain and the Netherlands will collapse, rivers will dry up, forests will be on fire, people will migrate to northern parts of the planet and the global economy will fall apart. You may say: I would like to be on a mountain in Switzerland, but actually it doesn’t matter where you will be. The best and the worst in people will come out in a situation where their lives are at stake. Lawrence Weiner’s Far Too Many Things to Fit Into So Small a Box could be seen as speaking to this as well”.

It would be easy to slip into a simplistic listing of similarities and differences between these two distinct exhibitions at the CCA. But both of them deserve a more detailed description.

The monographic exhibition of Karol Radziszewski’s works is to some extent a retrospective, as it seems to look chronologically at different stages of his practice, but it is primarily an installation, in which the artist creates an assemblage composed of his earliest and more recent works. The “childhood drawings which covered the pages of his school notebooks” (1989, 2017—ongoing, painting, acrylic on canvas; murals) depict figures of extremely femininity, at once Barbie and drag queen, together with other doodles in coloured felt-tip pen, through which Radziszewski dialogues with his preteen past. The innocent secret of a coming-of-age boy’s dream of being a princess becomes a radical statement, reenacted in a blown-up version on the walls of an institution. This entry backdrop becomes significant as it bridges past and present, a gesture that is also apparent in a series of paintings (O Snob, 2019, painting, acrylic on canvas) inspired by the front covers of an underground Brazilian queer magazine published in Rio in the 1960s, edited mostly by trans people using cosplay as a way of discovering identity.

ZR: You spoke of establishing historical continuity, that you were building a bridge for yourself and you were looking for identity, iconographic sources, some actions that would allow you to put yourself in context. But I also understand that at some point the mission began: you said that people seized on it and that it is also important for them. So from being a researcher for yourself, you became a researcher for others as well.

KR:There’s another important element here: this princess wearing glasses or the crucified princess… these are like my self-portraits. And it was also a surprise to me, something that I didn’t do too much in my art — and I don’t even mean drag, but entering this other sex, which suddenly appeared here as a child. It was surprise to me too. That’s why this princess is so huge. I have an awesome picture of my parents standing beside her and they are about half her size. So they stand alongside the great Karolina. I was supposed to be called Karolina.

The greater part of the exhibition is a non-linear collage of footnotes, artist’s findings and focus showcases, including the Queer Archive Institute in the central part of the exhibition with 22 Picasso-esque paintings (Poczet, 2017, paintings, acrylic on canvas) of non-heteronormative people from Polish history, looking out boldly at the viewer as if asserting their role as heroes (heroines?) of the QAI. Here, Radziszewski, in a way that is very significant for his practice as archivist or curator, shows other people’s work: a red (“carmine”) room dedicated to art historian and researcher Wojciech Skrodzki (Hommage à WS, 2019), which is an exhibition re-enactment co-curated with Szymański himself, or the archives of Ryszard Kisiel with extracts from Filo zine and props from his photo sessions, as well as a series of stills from a carnival party at the T-Club in Prague by Czech photographer Libuše Jarcovjáková (T-Club, 1983−1986, inkjet prints). “Gay and lesbian clubs in post-Soviet countries — hidden in cellars, behind unmarked doors, promoted by word of mouth were — the perhaps still are — the most formative centers of the queer community,” we read in the work’s description. Radziszewski also evokes the recent past of Europe’s margins: Belarusian (Invisible (Belarusian) Queer History, 2016, analogue photographs) and Ukrainian (Was Taras Shevchenko Gay?, 2017, installation), resonating well with Wolfgang Tillmans’ series of portraits from Saint-Petersburg (Saint Petersburg LGBT Community, 2014, chromogenic prints). The exhibition also shows an ever growing collection of videos by Karol Radziszewski, including a series of interviews focused on queer and trans protagonists, conceived during QAI residencies, and others created though invitations such as Interview with Laerte (2016, video, 39′) featuring Laerte Coutinho, a Brazilian artist and activist, and an interview with Ewa Hołuszko, a major and until recently overlooked figure in Poland’s Solidarity movement who had to confront attempts at exclusion due to her transition process (Interview with Ewa Hołuszko (fragments), 2019, video, 30′). Radziszewski is also the author of a number of other film productions, some of which are shown in the CCA’s cinema (Sebastian, 2010, 4’30”; MS 101, 2012, 50′; Backstage, 2011, 38′; The Prince, 2014, 71′), together with videos and films by other artists (Przemek Branas, Agne Jokse, Dawid Nickel and Liliana Piskorska).

ZR: Where do you keep your archive?

KR: In my bedroom, because one studio burnt down and the other was partly flooded. So there are only relics of the second category, like doubled magazines or VHS cassettes. But I keep negatives in boxes in the wardrobe with clothes.

ZR: I am sorry to hear that. Did you lose much that was valuable in these disasters?

KR: Well, five years ago I lost all my work up to the age of 29, everything I had done. Other than childhood notebooks, which were at my parents’ home, all of the work I did up to the end of my studies was burnt with the studio. Over a hundred paintings, polaroids, most of DIK’s archives, sketches, gifts from artists.

ZR: Oh no… and how do you feel as an artist-archivist who lost such a large part of his private archive?

KR: Well, apart from the trauma and the fact that I lost a lot of work, I also lost a lot of money — there were whole photo exhibitions that I had produced, 70 photos, large, hand-made prints in wooden frames that I had been working on for half a year. I can’t afford to do the whole series again. Then I moved to a small, clean studio, which was meant to be an office, and repainted three works that had been burnt. But I went away for a week and when I came back the ceiling had leaked (someone upstairs had a clogged bathtub) and the works that I had repainted after the fire were flooded. So, then I realized that it is… Having lived through this trauma, I felt that I didn’t want to be an archivist, I didn’t want to deal with this materiality, to be responsible for all this. There was a period when I wanted to get rid of it all, sell it to some institution, so that someone else would take responsibility for it. But it wasn’t possible, the years went by … And then I made movies. I had a clean white studio, I made films, I didn’t paint, I didn’t want to produce any material things at all, and I only had two small boxes with these archives. The exhibition dedicated to DIK Fagazine and the archive of my magazine had been packed into a box after the exhibition and was in the middle of the studio that burnt down, so it was also burnt, the box containing all that.

ZR:So you self-archived your works, and they got lost anyway…

KR: Yes, and I thought long and hard at that point about what to do, because I didn’t want to have it on my mind. But the months and years went by […] and the archives began to accumulate again.

[…]

ZR: And what about Polish lesbian artists who might want to look for some kind of continuity for themselves?

KR: The biggest success is the cooperation with Liliana Piskorska, which is not just history — it is something we are building into the future. We have [shown and — K.R.] produced her works twice as part of the Pomada festivals. They became part of the narrative and I believe that this has also given her more mainstream visibility. […] The Queer Archives collection is also intended to create contemporary queer art, following the tradition of an exchange gallery. So I exchange works with other artists. And everyone is usually younger than me, because it is all such a fresh topic. People are happy to exchange, and I create a private collection — but also as part of the Queer Archives — of the queer art of the region, and that is a source of strength. These are not historical works or strictly an artistic cooperation, but my works resonate with them, and I choose them, so that I already have the beginnings of a pretty cool collection. I have drawings by Tolik [Anatoly] Belov, [ 31 ] 31. Anatoly Belov (Анатолій Бєлов, Anatolij Biełow, b. 1977) – visual artist based in Kiev, interested in the issue of non-heteronormativity in Ukraine. See: https://labirynt.com/attentionborder/en/anatoly-belov-2, https://mocak.pl/artist/3832/sex-medicated-rock-n-roll. a Ukrainian, from the period when he started working openly as the first gay [artist — K.R.], so I can put this together [with mine]. I have drawings of his daughter, whom he adopted, which also interest me — the issue of queer children. I also have Polish artists — I exchange work with Liliana. I will also create a collection of contemporary Eastern European queer art that will travel and also various curators could arrange their own travelling exhibitions. So there are a lot of plans for the future.

These two solo presentations accentuating archives as their method are widely inclusive and open-format shows where different bodies tell their own stories. The Power of Secrets begins with the queer childhood of the artist and each feature becomes a QAI artefact extending through the exhibition rooms. The creativity of Natalia LL, whose solo exhibition Secretum et Tremor was presented exactly three years ago at the CCA, works very well in this context. Her work Dulce-Post Mortem, 2019 (photographs of three neon lights tracing abstract characters) seems to conclude the exhibition.

Stressing the status of Far Too Many Stories… as an exhibition in motion, curator Joanna Zielińska says that “Even the work by Alina Szapocznikow, considered to be the beginning of the collection, was loaned from 2002 and will soon be taken back to its owner”. The show works both as a solo and collaborative proposal with countless voices gathered for its making, the objects selected according to the interlocutors’ visions, voices by Ania Nowak and Billy Morgan coming from speakers in an audioscape designed by Wojciech Blecharz, and with posters designed by the Warsaw duo Fontarte. Bik Van der Pol’s exhibition is a site-specific installation looking at the CCA’s past and its traditions and can serve to locate the current position of the Centre and its future programme. Far Too Many Stories and Power of Secrets testify to the Centre’s resilience, its ability to present different types of archival matter and artistic research. “The archives are useful. This is activism. It is the core business of the Centre”, as one of the voices suggests.

ZR: In socially-engaged research, anthropological or ethnographic, there is the concept of “action research” — you meet, act with a community, because you want to acquire some knowledge, create something, but also to improve their situation. Is it something you can relate to? Are you interested in such research, in a change-making activity?

KR: You know, I certainly care about change-making, but I’m not always able to use these methods because they take time. So, depending on the country and situation, I unfortunately have to step into the role of someone who kindles something, continues, tosses it and often people just continue in some other way. This happened in Minsk, where as well as meeting with historians, I met with activists and we just talked for an hour and they said that they were also starting archives, they took out my DIKs, my magazines, which they had somehow got on the Internet, which they already had at home, and they asked me where to begin. It was a kind of workshop, a very specific one.

Those two exhibitions, as critical inquiries into the past and possible futures of Polish institutions mark a turning point and a new chapter in the history of the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art. A major shift in the CCA’s programme is expected after the conservative Piotr Bernatowicz [ 32 ] 32. Alex Marshall, "A Polish Museum Turns to the Right, and Artists Turn Away", The New York Times 8.01.2020. was appointed director of the institution at the start of 2020. The nomination has evoked substantial concern both at the liberal end of the Polish art scene and internationally. [ 33 ] 33. Alex Marshall, "A Polish Museum Turns to the Right, and Artists Turn Away", The New York Times 8.01.2020. The CCA is a pioneering contemporary art centre in Poland, its history collates with the history of democratic transformation in Poland after 1989 and it has always been perceived a cutting-edge site for bold and critical exhibitions and presentations, a flag bearer since the 1990s for freedom of speech and the polyphonic blooming of intersecting narratives and perspectives, as Bik Van der Pol has clearly showed in the latest exhibition. For three decades (notably under Wojciech Krukowski, from 1990 till 2010) CCA was not just an institutional role model for other galleries in Poland (though, of course, with its own issues and flaws), but also a place where artistic dialogue with the audience and open cultural and political debate were shaped – a genuine agora. One might ask: will the latest exploratory exhibition be enough for this narrative to be sustained or will it be altered? Will it preserve collective memory? Will the CAA transform into an even more spacious shelter for cultural micronarratives, including overlooked conservative voices, as Bernatowicz declares, but without banishing liberal voices? Ujazdowski Castle remains one of the leading art institutions in Poland, with huge impact on the Polish contemporary art scene, and these two exhibitions raise the more general question how the historical narrative of contemporary art and its future will be reshaped. Hopefully, the narrative will become not only polyphonic, but even more heterogeneous and less centre-oriented.

Acknowledgements: Michał Grzegorzek, Billy Morgan, Karol Radziszewski, Joanna Zielińska, Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art

- All quotes are based on a conversation between Romuald Demidenko and Joanna Zielińska that took place on 21.12.2019.

- Also known as "Movement Academy". Akademia Ruchu. Miasto. Pole akcji = City. The Field of Action, ed. Małgorzata Borkowska (Warszawa: Stowarzyszenie Przyjaciół Akademii Ruchu, 2006). Some of the works are in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (Accessed 30 Dec 2019).

- Karol Radziszewski, Invisible (Belarusian Queer History), 2016, a series of five analogue photographs with handwritten notes in Belarusian.

- DIK Fagazine No 8 / BEFORE '89, dikfagazine.blogspot.com 06.10.2011.

- Ryszard Kisiel, b. 1948 – one of the first gay activists in post-war Poland. Creator of Filo magazine, the second (after ETAP) Polish LGBT periodical, a monthly issued from 1986 to 2001 that contained news, reportage, prose, interviews, readers' texts, crosswords, tips, music charts, horoscopes, soft erotica, personal ads and an events calendar. See: "Ryszard Kisiel" in: Encyklopedia LGBT 26.04.2015; "Filo (miesięcznik)" in: pl.wikipedia.org 20.11.2019; "DIK and Kisieland at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw", dikfagazine.blogspot.com 2.05.2012.

- Ryszard Kisiel created an underground archive of colour slides documenting private photographic sessions made at the turn of 1985/1986 in response to the infamous Operation Hyacinth (a clampdown on homosexuals by the Polish secret police). Karol Radziszewski, Kisieland, 2012, https://artmuseum.pl/en/kolekcja/praca/radziszewski-karol-kisieland.

- An interview with Karol Radziszewski by Zofia Reznik on 06.12.2019 at the CCA Ujazdowski Castle, Warsaw. With the participation of Radziszewski's friends, Bartosz Geller and Łukasz Wójcik. Audio recording in the archives of Zofia Reznik. Translation and all notes by Zofia Reznik, unless otherwise stated.

- "Filo" might be read as a reference to the greek φίλος (phílos), meaning "dear" or "beloved", but also "a friend" or "a boyfriend", and "Filo" in Greek could be a masculine or neuter dual form, therefore signifying "two dears" or "two boyfriends"; see: "φίλος" in: en.wiktionary.org 23.08.2019.

- Karol Radziszewski and Wojciech Szymański curated the monographic show Cruising dedicated to Ryszard Kisiel's archives, Gdańsk City Gallery, 2018.

- Queer Archives Institute was founded by Karol Radziszewski in November 2015 as an independent organisation, "dedicated to research, collection, digitalisation, presentation, exhibition, analysis and artistic interpretation of queer archives, with special focus on Central and Eastern Europe". See: http://queerarchivesinstitute.org. The presentation of QAI was the core part of Radziszewski's exhibition. A year later, in 2016, a similar archival project entitled "And LGBT culture won't wait!" ("A kultura LGBT nie poczeka!") was started by a lesbian duo, Agnieszka Małgowska and Monika Rak, who are virtually archiving the cultural activities of the Polish LGBTQ+ scene, see: http://akulturalgbtq.pl.

- Wojciech Skrodzki presents the exhibition Hommage to Andrzej Matynia (Wojciech Skrodzki przedstawia wystawę "Hommage Andrzejowi Matyni"), 1978/1979, The Critics Gallery (Galeria Krytyków), Warszawa.

- Natalia LL, Natalia Lach-Lachowicz, b, 1937 – Polish visual artist based in Wrocław, known for photographic works, films, performances and texts on art, co-founder of the PERMAFO gallery, often associated with feminism. Her most well-known works include Intimate Photography (1971), Consumer Art (from 1972) and Post-consumer Art (1975). See: Krzysztof Jurecki, "Natalia LL", translated by Sylwia Wojda, culture.pl 2011. Her photos depicting naked female body were part of Skrodzki's original and reenacted exhibition.

- The Dead Class (1975) is the best-known work of the Polish artist and performer, Tadeusz Kantor (1915-1990). It was premiered at the Krzysztofory Gallery in Kraków, performed in many countries around the world and widely acclaimed by critics. It tells the story of elderly men who revisit their past and confront the impossibility of returning to one's childhood and also of the outbreak of World War II. See: Karolina Czerska, "The Dead Class – Tadeusz Kantor", transl. M.K., culture.pl 2014; Tadeusz Kantor, The Dead Class, 1976, https://artmuseum.pl/en/filmoteka/praca/kantor-tadeusz-umarla-klasa.

- A remark of Łukasz Wójcik.

- Operation Hyacinth (1985–1987) was a large-scale operation by the Polish secret police to gather information on Polish homosexuals and their circle. About 11,000 people were registered, files were opened on them and many persons were arrested (those arrested had special files opened and often had to sign a statement). The operation drove members of the gay community underground. See: "Operation Hyacinth", in: Wikipedia.org 03.01.2020.

- Neue Wilde, Junge Wilde – a painting style that grew in popularity mainly in Germany at the end of 1970s and had its heyday in the first half of the next decade. It was linked to the Italian Transavantgarde, American neo-expressionism and French Figuration Libre. See: "Neue Wilde", in: de.wikipedia.org 27.08.2019.

- A. R. Penck (Ralf Winkler, 1939–2017) – German visual artist born in Dresden; Georg Baselitz (b. 1938) – German painter and sculptor; Jörg Immendorf (1945–2007) – German visual artist and scholar.

- Keith Haring (1958–1990) – American artist known for using pop art and graffiti-like aesthetics and for addressing homosexuality and AIDS.

- A. R. Penck, West, 1980, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/penck-west-t03303.

- The Ministry of Public Security or Department of Security ("Urząd Bezpieczeństwa") was the Polish secret police and intelligence service from 1945 to 1954. In 1956 the Department of Security was renamed the Security Service ("Służba Bezpieczeństwa") and continued to operate until 1989. See: "Ministry of Public Security (Poland)" in: wikipedia.org 06.01.2020; "Służba Bezpieczeństwa", in: wikipedia.org 13.12.2019.

- Karol Radziszewski, Mushroom (Grzybek), 2019, steel sculpture. Radziszewski's sculpture is a reference to one of popular cruising spots – a public toilet (no longer existent), shaped like a mushroom, standing on Three Crosses Square in Warsaw. The work mimics the style of the famous Polish sculptor Monika Sosnowska (b. 1972), who often addresses issues of socio-political change as manifested in architecture. The crushed and distorted form of the sculpture refers to its demolition.

- https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/27/world/europe/gay-pride-march-poland-violence.html (accessed 30 Dec 2019).

- Working Title: Archive, Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, Poland, 27 February – 3 May 2009, curated by Magdalena Ziółkowska, with work and texts by authors including Marysia Lewandowska and Lasse Schmidt Hansen; See: Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Innovative Forms of Archives, Part One: Exhibitions, Events, Books, Museums, and Lia Perjovschi's Contemporary Art Archive, e-flux Journal #13 - February 2010 (Accessed 30 Dec 2019).

- Enthusiasts: archive. A project by Neil Cummings and Marysia Lewandowska, launched in October 2019, www.entuzjasci.artmuseum.pl/en/about/ (Accessed 30 Dec 2019).

- Karol Radziszewski, Faggots (Pedały), 2005, private apartment, Warsaw. See: Joanna Sokołowska, "Pedały Karola Radziszewskiego", Obieg 24.06.2005.

- Paweł Leszkowicz (b. 1970) – Polish art historian and scholar, curator of the exhibition Ars Homo Erotica (2010) at the National Museum in Warsaw.

- Karol Radziszewski, Fellowship (Poczet), 2017, series of 22 paintings showing non-heteronormative people from the history of Poland. It is also a reference to Jan Matejko's famous series of drawings Gallery of Polish Kings, 1890–1892. See: https://artmuseum.pl/pl/kolekcja/praca/radziszewski-karol-poczet.

- See: The Book Lovers, ed. David Maroto and Joanna Zielińska, Sternberg Press, 2015.

- Radziszewski's studio and the studios of other artists were damaged in a fire in 2013. See: Zuzanna Janin, "Dzieła sztuki współczesnej i pracownie artystów zniknęły w pożarze kamienicy w Warszawie", natemat.pl 30.01.2013.

- Karol Radziszewski, Afterimages, 2018, film, 15'. See: https://archiwum2019.mdag.pl/16/en/warszawa/movie/Powidoki; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZOK8HgMgr6g.

- Anatoly Belov (Анатолій Бєлов, Anatolij Biełow, b. 1977) – visual artist based in Kiev, interested in the issue of non-heteronormativity in Ukraine. See: https://labirynt.com/attentionborder/en/anatoly-belov-2, https://mocak.pl/artist/3832/sex-medicated-rock-n-roll.

- Alex Marshall, "A Polish Museum Turns to the Right, and Artists Turn Away", The New York Times 8.01.2020.

- Alex Marshall, "A Polish Museum Turns to the Right, and Artists Turn Away", The New York Times 8.01.2020.