art in isolation: the home cinema as echo-chamber

Chloe Hodge explores independent art experiences online and how they are received by the isolated mind, affected by the distraction and anxiety of the pandemic.

What is the difference between a cinema and a gallery? Both are public entertainment venues which screen their films in darkened rooms, populated by an audience of friends and strangers. The contrast is in the way that the audience inhabits these spaces. When we enter a cinema, we take our allocated seat and sit static and silent in pitch black, as we absorb a feature film from beginning to end. We might break the quietude to gasp at a horror movie, laugh at a comedy, or even sob at the end of tragedy – yet these are solo, not intentionally sociable, actions. The promotional trailer is the only contextual material sought by the average viewer, and the aim of watching the film is not to engage in a dialogue. The viewer is isolated and immobilised in a sealed space, building an independent experience.

Meanwhile, the dimly-lit screening room of a gallery is fundamentally designed to encourage interaction and movement: audiences walk in through an open doorway or gently-hung curtain, they often remain standing as a curator will rarely provide audiences with a cushioned seat, even when showing hours-long artist films. There is no formal obligation to watch an artist film from beginning to end. We do not view this as a problem as no doubt the work in question will be prefaced by a guiding curatorial text and as we drift in and out screenings, we will overhear and engage in discussion about the work. Unlike blockbusters, films as artwork exist inside an institution as part of a collection or exhibition, and as part of an ongoing canon to be interrogated. With this discursive approach, we accept art-viewing as teamwork: introductory panels and guidebooks lay the foundations and raise the frame, our experience of the artwork bricks in the walls and gives the building its shape, and social interactions thatch the roof and seal any holes.

However, in 2021, we find ourselves acting as the master-builder of our experiences. The Covid-19 pandemic and its resulting lockdowns have seated the majority of us firmly at home: solo, static, silent, sunk staring at screens in our own cushioned seats. Our homes have become the cinema, and the doors are locked for the duration. And to entertain locked-down arts audiences, international institutions have transported digital artwork experiences online.

Rhizome, possibly the first internet art organisation having been established in Berlin in 1996, has uploaded the archive of its First Look programme to the web. Produced in partnership with The New Museum in New York, this means that at-home viewers can watch numerous digital commissions online, dating back to 2012.

Meanwhile, multidisciplinary arts organisation Performa has established its online channel Radical Broadcast. While Performa would usually be commissioning live works, running international tours or coordinating the next edition of the only live performance-based biennial in the world, Radical Broadcast has been designed to situate performative artworks online. To mirror the experience of a live, timed performance, its screening programmes always start at the same hour, regardless of your time zone – for example, their spring 2021 programme LEAN begins with screenings at 9am, whether you’re in Moscow or London.

Then there is Daata, which commissions and sells digital artworks by emerging and renowned international artists, and in 2020 presented the first exclusively online art fair, conversely titled Daata Miami. Although a keenly commercial venture, Daata’s commissions are available to stream for free, while its low-cost subscription service DaataTV was also established in 2020 to allow paid users to create their own digital art playlists.

In London, there is This Is Public Space, an online programme by non-profit public art organisation UP Projects. Like Daata, This Is Public Space produces new digital commissions, however these are designed to be experienced exclusively on the web – considering the internet as another kind of public space.

Aside from a surround-sound system and 8K display, there appears to be little to differentiate viewing digital artworks at home from inside a gallery (the human eye cannot actually differentiate between 4K and 8K resolution, anyway). Comfortably seated at our computers, without fellow audience members moving across the screen, fidgeting besides us or talking over artwork dialogue, are we not better set to immerse ourselves in the works here, to do them justice? In a sense, yes. A home setting seems as if it would optimise concentration – trusting that we have first switched off our screen’s email alerts, social media notifications, and news updates. With our fingers on the touchpad, we have full control over the work: we can easily arrive at or decide upon an artwork’s start time, we can zoom in, raise the volume or rewind anything that we miss, we can even pause to Google search anything that we don’t quite understand – or just sift through Instagram to find that actor we think we recognise…

This is where the problems begin. As contemporary human beings, we are already playing host to a distracted mind. In the digital age, we are surrounded by constant distractions, while ever-accessible online information frees us from having to commit anything to memory. Prior to the pandemic, the average human attention span had already dropped to less than that of a goldfish – eight seconds, in comparison to their nine – and the problem is only getting worse.

Over the past year of intermittent lockdowns and increased time online there has been a 300% rise in the Google search “how to get your brain to focus,” and similar statistics for “how to focus better,” and the disgruntled “why can’t I focus?” All over the world, people are living and working online and in isolation, which has furthered the severity of our attention deficit disorder. When we are alone and lacking in social comforts, we are more likely to reach for our mobile phones to check in with friends, or to immediately attend to the ping of an email or social media alert. It is natural to look for social interaction in times of loneliness and, in the short term, this habit just seems like harmless procrastination. However, it is deeply disrupting and physiologically near impossible to break. Each time we receive a message or online ‘Like’ our brain releases a rush of dopamine into its reward pathways. This chemical hit is by nature addictive, and it is the same reason that people return to other bad habits, like overeating, gambling or substance abuse – otherwise known as addictions. Unlike in private, in public spaces addictive behaviours are fairly easy to manage as they are not socially acceptable, which is the same for digital addictions. Tapping away on the glowing blue face of your iPhone would soon have you ushered out of a gallery screening room, and all commercial movies are prefaced by the title-card “Please Turn Off Your Mobile Phone.”

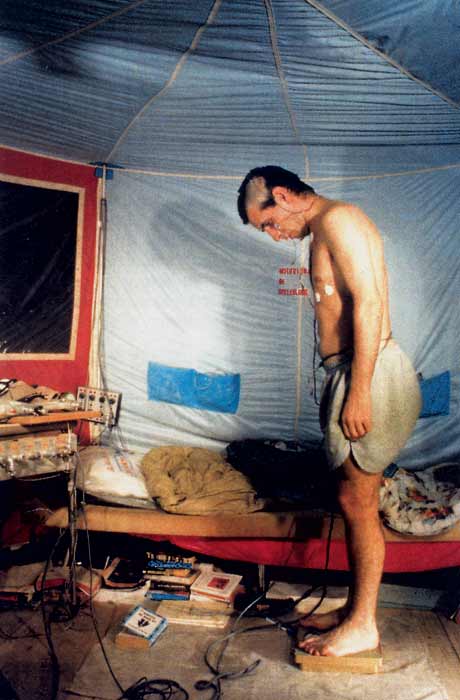

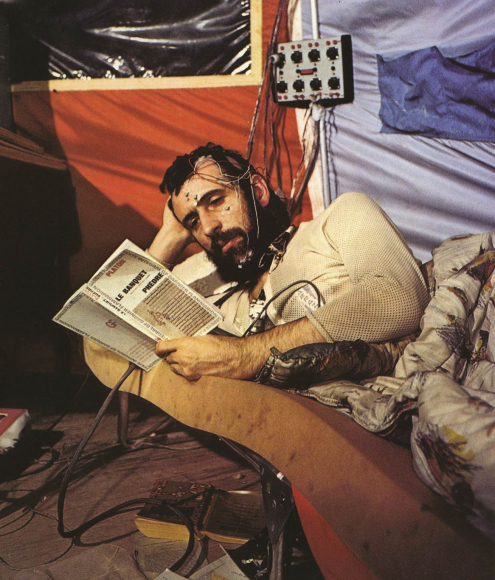

Alone time not only depletes our attention span by digital proxy. Experiments over the past fifty years all point to the conclusion that social isolation directly leads to a lack of focus. The nature of these studies range from French scientist Michel Siffre’s 205-day quarantine in a cave in 1972, to analysing behaviour change in prisoners in solitary confinement, and the biannual English Longitudinal Study of Ageing which has surveyed over 18,000 isolated elderly people since 2002.

Like our digital addiction, this is biological: a cognitive decline due to hormone imbalances and reduced levels of healthy, signal-firing matter in the brain. Isolation can cause dysregulated signalling in the prefrontal cortex, which controls decision-making. It can even decrease the size of a person’s hippocampus which has a major role in learning and memory, and lead to higher levels of the stress hormone cortisol which further impairs these functions. And, the amygdalae, two almond-shaped brain areas which process emotional response, are often smaller if a person is lonely. Put simply, when we are unusually isolated we cannot make clear decisions, learn or remember in the same way, and our emotional reactions are skewed.

In addition to lessening our ability to think straight through social distancing, the Covid-19 pandemic has created a climate of instability and fear. Though we may not feel palpably afraid, many of us will have spent several months in ‘fight or flight’ mode. This becomes visible in actions such as jumping across the pavement from a passer-by, the rush to sanitise one’s hands, and understandable upset and worry if you or your loved ones are unwell. However, our body’s desire to fight or fly often manifests in a less noticeable way, quietly arising as we read the news. And, with a constant flow of digital information travelling into the palms of our hands and onto our laptop screens, this news is more inescapable than ever. Rather than be sustained long term, fight or flight is designed to protect us from immediate danger and so we become hyperaware, scan for threats, and are less able to produce complex thoughts – as we don’t need to, when running from a predator. Rendered animalistic via fight or flight mode, cognitively impaired through ongoing isolation, and perpetually distracted by the dopamine draw of our digital devices, focus is a problem in 2021.

When the master-builder cannot concentrate, building anything well-considered is rather difficult – and, acting solo, he has no teammates to fill in the gaps that he has missed.

Still, while lacking in sociable ‘IRL’ colleagues, it could be argued that when viewing artworks online we have immediate access to the most efficient and knowledgeable workforce there ever has been: the Internet. This is true. As we watch alone with our screens in arm’s reach, technology is readily available to fill in the gaps. A new tab or two, to sit alongside the artwork. A new window, sandwiching over the work with a different browser. A quick spin through Instagram on your smartphone. We are free to Pause, research, Play, as many times as we like. As one Google transforms into eleven different websites, checking site authors’ Twitter profiles along the way, it may take us three hours to watch a twenty-minute film work – though in lockdown, it can feel as if we have all the time in the world to spare.

To build our own unique, independently researched experience may seem positive. In the gallery, our view is primarily shaped by a curator’s text, written by one individual or two. In turn, their opinion has been shaped by the art world, its trending themes and gallerists’ picks (based on market worth). Among a mass of contextualisation, it can be difficult to identify whether or not you really like an artwork – especially if everyone and everything that surrounds you tells you that it is great. Art is still allowed to be subject to taste. Giving viewers space to form subjective understandings and to think alone is surely a good thing. The ability for this to rise out of an online context is, nevertheless, naïve.

In recent years we have seen the danger of grounding one’s worldview in the worldwide web. Online, a complete and universal knowledge may seem available yet there is no single online realm. Instead, we are all presented with different realms, populated by different personalities and different facts. The content that we read online depends upon the resources that we use, our location and online histories. For any given search, the first page of my Google results will most likely be different to yours. If you use a different search engine to me, backed by different advertisers with different vested interests, your results will be different again. My social media platforms will suggest I read alternate articles to you, and follow other people, based on whatever and whomever I already like or Like. The internet is a series of strands which lead users in whichever direction means a higher dwell-time and more impressions. Because, our attention is monetised.

If our personal realms simply educated us in separate areas of knowledge, that could be useful and we would build between us a varied and balanced workforce. However, our attention is being channelled towards online personalities and information which are carefully curated. Replacing the truth with a more appealing and popular (or populist) version is what people do online. And regardless of platform, your newsfeed is only designed to hold your attention – it does not know what is fact or fiction, what is balanced or extreme. At its most shallow, this means that the actor you searched on Instagram has deleted their posts about that failed movie role: their climb to stardom, untainted. However, the implications of online deceit can be far darker than a hidden box office flop. At its most extreme, the concentrating mechanisms of the internet lead into a tight echo-chamber of congratulatory or cynical chorus. IRL, this has apparated in events such as political uprisings instigated through Facebook; the election of the world’s first President to rally and rule via social media; and the transformation of ordinary people into Covid-19 conspiracy theorists. Fake news spreads six times faster on Twitter and polarisation is at a 20-year high.

When real-life teamwork is outsourced to an online workforce, the structure of our experience is left vulnerable to poor craftsmanship. It is the real-life social environment of viewing art in public that can prevent us from reaching for our phone. It is the real-life social environment of viewing art in public that enables us to fill in the gaps with discussion. And it is the real-life social environment of viewing art in public that enables us to interrogate information around an artwork together, to listen to opposing opinions, in a way that we cannot when accumulating content alone online.

Here the question arises, in lockdown and in lieu of real-life social environments, could we purify the home cinema: rid ourselves of digital distraction, and attempt to absorb artworks as unique insular experiences? This is a possibility, yet remains far from the context in which most video art was intended to be seen.

Or, do we work towards creating a social environment online? It’s possible to host group film screenings together on Zoom or Google Hangouts, with one user sharing their screen and the rest watching. Only one person at a time can speak over the film and their words slice through the film’s audio, as these platforms cannot play multiple sounds simultaneously, yet at least there is conversation. Streaming services like Netflix, Hulu, Scener and Amazon also enable communal viewings, some hosting up to 50 people. However, the chat is text, snatching the focus from watching to reading. Or, it’s possible to coordinate joint screenings of any movie by simply chatting on a shared WhatsApp or WeChat group and clicking Play in unison, swimming while viewing in the deep blue dopamine pool. Still, in each of these scenarios, your teammates are not diverse colleagues at work, but friends.

Are these options good enough, or do we instead go to the root of the problem? In the present moment, our brains are programmed to distraction by time online, our ability to concentrate has been damaged through isolation, and further aggravated by the ‘fight or flight’ mode caused by the absorption of digital news, some of which is misinformation. Perhaps, rather than continue to develop our digital options, we could pause and think about which media used to comfort and satiate people in times of quiet, and could help our contemporary condition.

Here, reading, rather than viewing, might be the key.

The very act of decoding symbols into letters, letters into words, and words into thoughts has been proven to restore the parts of the brain dissolved by screen time. To read requires a multitude of actions: word analysis and auditory detection, vocalization and visualization, phonemic awareness and fluency. This is before we even reach the importance of comprehending a narrative text. When we read a book, we absorb sentences and paragraphs in a linear way, and process the narrative sequentially; we must remember yesterday’s reading to understand today’s – all of this exercises our memory. And, while we tend to split our online attention, bouncing sporadically from tab to tab, reading requires sustained, unbroken focus which exercises our attention span. Reading can even enhance our ability to empathise and supports feelings of socialisation as, while we read, neurons in the brain react similarly to if we were experiencing the written sensations. In this sense, reading does not only show us character scenarios, but biologically places us in the bodies and company of the characters. Crucially for the current moment, reading is proven to reduce stress and anxiety more than walking, drinking tea, listening to music – and of course, spending time online. And, it has always been carried out solo, silent, static.

Together, we will return to the dimly-lit spaces, 8K screens and surround sound of the galleries, in which artworks were meant to be seen. In the meantime, we can take a moment to heal our minds and hone our skills as a brighter, more able workforce, with a focus, attention to detail and patience. If we are to take one thing from the home cinema, it might be to “please turn off our mobile phones” but instead of viewing, to switch on the lights and try picking up a book.